With Cities Facing Fiscal Challenges, a Few Try Tax Reform

Philadelphia, for one, appoints a commission to weigh broad changes

Many cities will face fiscal challenges in 2025 despite having relatively strong economies—a result of several factors, including revenue dips due to new commuting patterns and the coming expiration of funds from the federal American Rescue Plan Act. As cities adjust their budgets to cope with this reality, a handful have either proposed or attempted fundamental shifts in their tax burdens.

For example, in an effort to combat an exodus of businesses from the city, San Francisco voters in November approved new tax rules that will let businesses reduce the share of their gross receipts that are subject to taxation. Boston tried but failed to win state legislative approval to rebalance its residential and commercial property taxes, a move designed to cope with falling commercial assessments. St. Louis has established an advisory council to examine alternatives to the city’s earnings tax.

In Philadelphia, to give the city some revenue flexibility in 2024 and 2025, Mayor Cherelle Parker and City Council agreed in early 2024 to halt previously scheduled incremental rate cuts in the city’s taxes on business and personal income. They also convened a tax reform commission to examine and recommend other changes for the fiscal year that begins July 1, 2025 (and subsequent fiscal years); the commission’s report is expected early this year.

The commission invited The Pew Charitable Trusts, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization founded in the city, to provide technical assistance. In that capacity, Pew offered policy considerations, some of which may have relevance to other cities as well.

Tax burdens and city-state collaboration

Increased city-state collaboration may help reduce tax burdens by improving the administration of tax relief programs for residents and businesses.

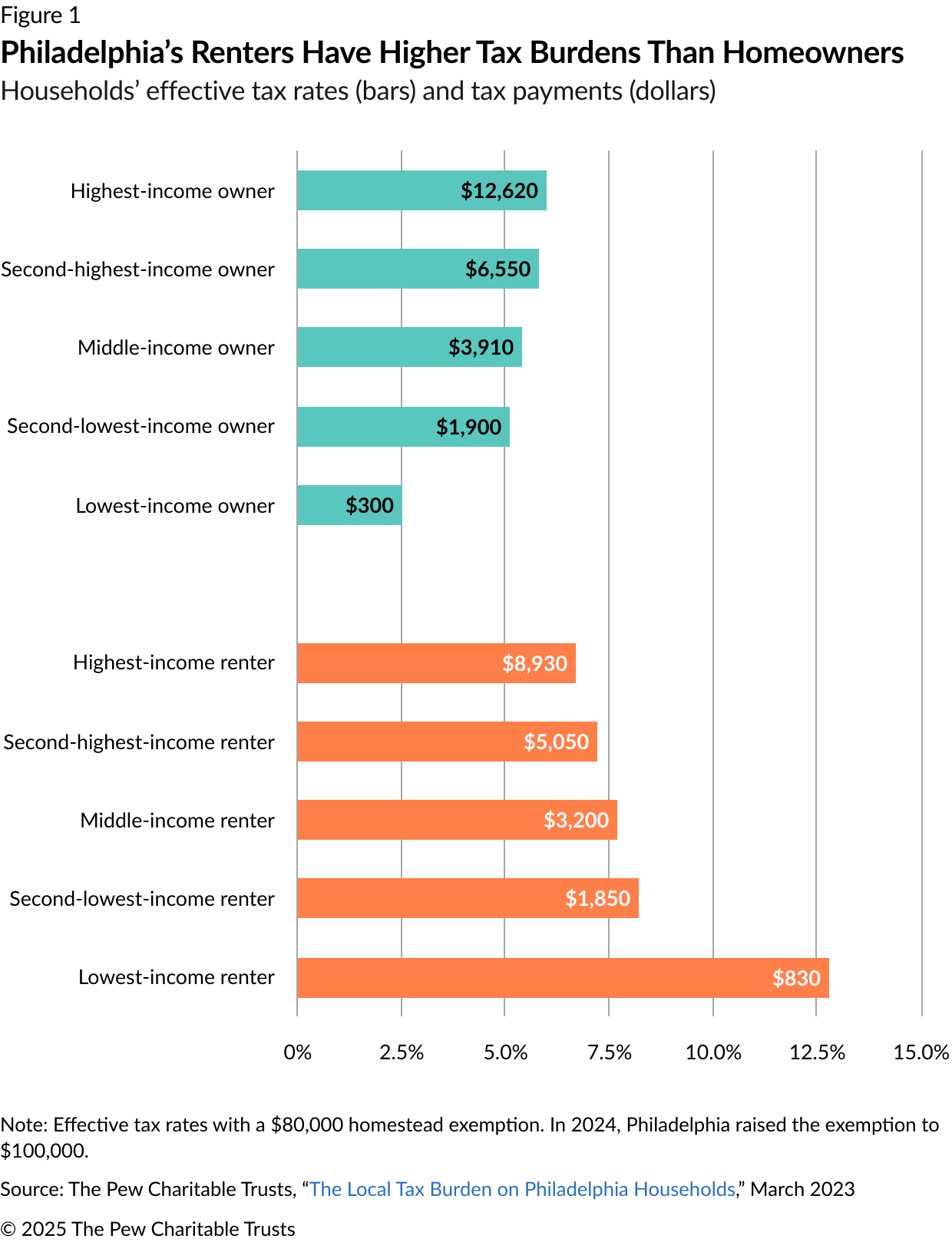

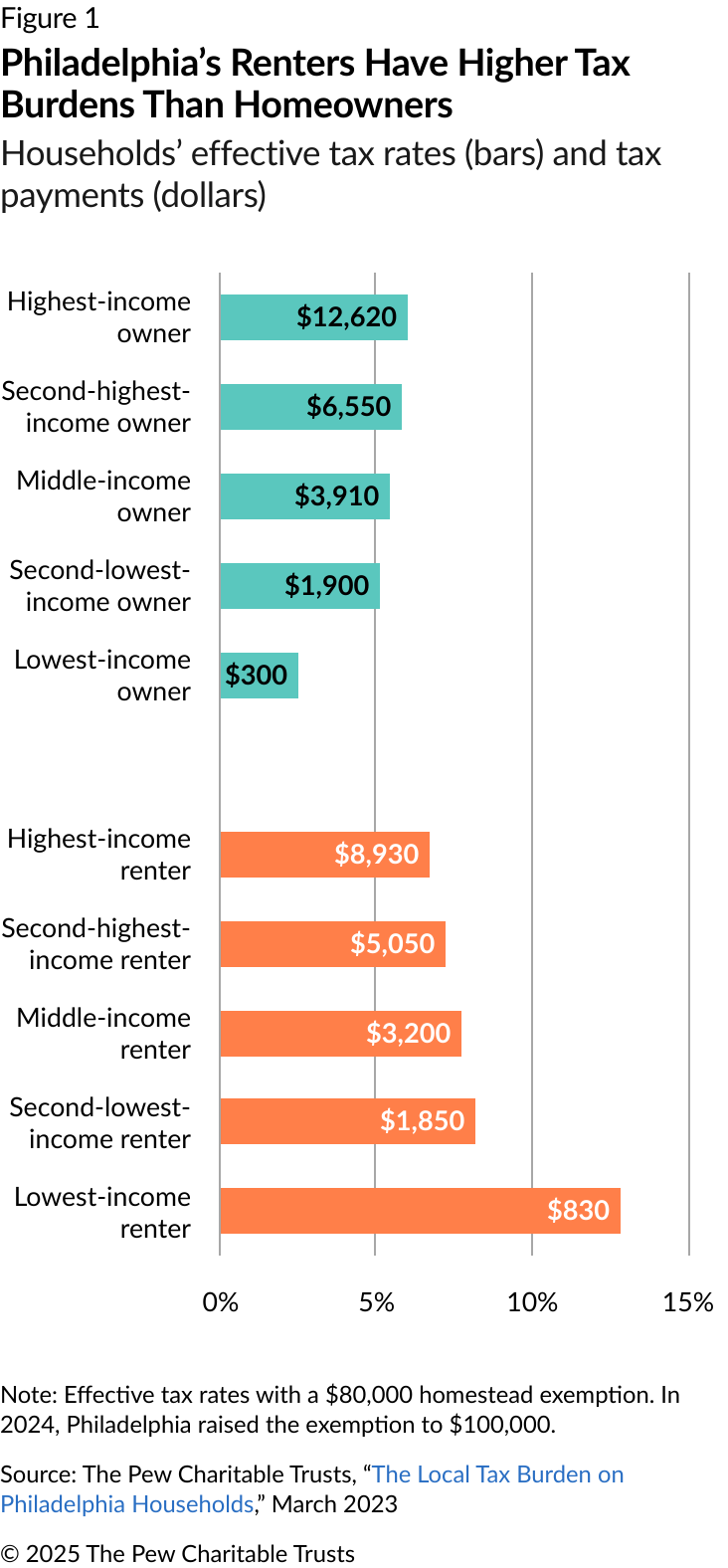

Pew’s research on Philadelphia’s residential tax burden found that the city’s overall tax structure has been mildly progressive for homeowners, mainly because of a relatively generous homestead exemption. But it is regressive for renters with no public subsidy for housing, who typically shoulder the cost of taxes in their rent payment but aren’t eligible for the homestead or other property-related exemptions, which offset the city’s “flat” tax rates and are required by the state constitution (see Figure 1). (In a regressive tax structure with identical flat rates for everybody, a decrease in a taxpayer’s income results in a higher tax burden, while in a progressive structure with variable tax rates, a decrease in a taxpayer’s income normally results in a lower tax burden.)

The high effective tax rate for low-income renters, as well as high wage taxes in general in Philadelphia, might be mitigated somewhat by increasing participation in existing tax relief programs through closer city-state collaboration. One city program piggybacks on a state program to reduce the income taxes that low-income wage-earners owe in Philadelphia, while a separate state-run program provides a rebate on certain housing or tax costs that low-income renters pay locally. Currently, participation by Philadelphia residents in both programs is lower than the number that city officials believe are eligible.

Business tax incentives and evaluations

In assessing their tax systems, cities also would be well advised to regularly reexamine the tax incentives they offer businesses.

Such programs are a big part of the tax structure in Philadelphia, which is unusual among major U.S. cities in that it taxes both the net income and gross receipts of businesses through the business income and receipts tax (BIRT), the largest of the city’s many levies on businesses. Years of battles over the tax have resulted in a variety of tax incentives and exemptions, including a full BIRT exemption for businesses that generate less than $100,000 in annual gross receipts.

While this $100,000 exemption has been meaningful for very small and young businesses, inflation has eroded its value since its launch in 2014. Pew suggested that the commission look for ways to increase the exemption in line with inflation, and reiterated the need for Philadelphia to continue conducting rigorous evaluations and other analyses to determine whether its tax programs and rules meet their stated goals—and pay off for taxpayers.

As cities across the U.S. face shifting economic realities and the decline of federal financial aid, they’re weighing changes that will provide sustainable and equitable revenues without overburdening residents and businesses. Such tax changes, though sometimes small or incremental, can improve a city’s tax system and provide meaningful value for taxpayers.

Thomas Ginsberg is a senior officer in Pew’s Philadelphia research and policy initiative.