Immigrants’ Economic and Fiscal Role in Philadelphia

Foreign-born residents fill jobs and own homes and small businesses but also bring costs for the city

Immigrants play an outsize role in Philadelphia’s economy. They fill jobs, create businesses, own homes, and fuel entire industries at rates beyond their growing share of the city’s population (15.7% as of 2022). And their taxes help pay for public services and pensions.

But they also bring short-term costs for the city. With relatively low incomes, foreign-born Philadelphians, as a group, increase the need for services that their taxes may not fully cover, such as public schools, health care, language access services, and worker protections. A rising share of city residents living below the poverty line was born abroad.

Still, on balance, the long-term economic and fiscal gains that immigrants bring to Philadelphia could outweigh these short-term costs if immigrants stay and make progress financially, although how much gain and time this requires are hard to quantify. Studies at the national level show that low-income immigrants and their children typically go on to earn higher incomes, pay more taxes, and become major net contributors to economies and government coffers—hallmarks of economic mobility. At the local level, those gains might depend on the city retaining immigrants and their economic contributions, rather than losing them to other U.S. cities or states. Philadelphia now has many immigrant-focused associations and agencies, which can play a major role in retaining and activating these populations for the area’s long-term benefit.

Filling jobs and fueling industries

From 2010 to 2022 (the latest year for which full data was available), the number of foreign-born Philadelphians in the region’s civilian labor force rose from around 105,600 to 158,300, according to The Pew Charitable Trusts’ analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. That 50% increase outpaced the percentages for the nation and most of the comparison cities. Over that period, immigrants accounted for a third of the increase in the city’s overall employed labor force, helping raise that number to 756,000, the highest in decades. They also fed the suburbs’ need for workers: Around 15% of Philadelphians born abroad commuted to jobs outside the city, higher than the 9% rate for U.S.-born workers.

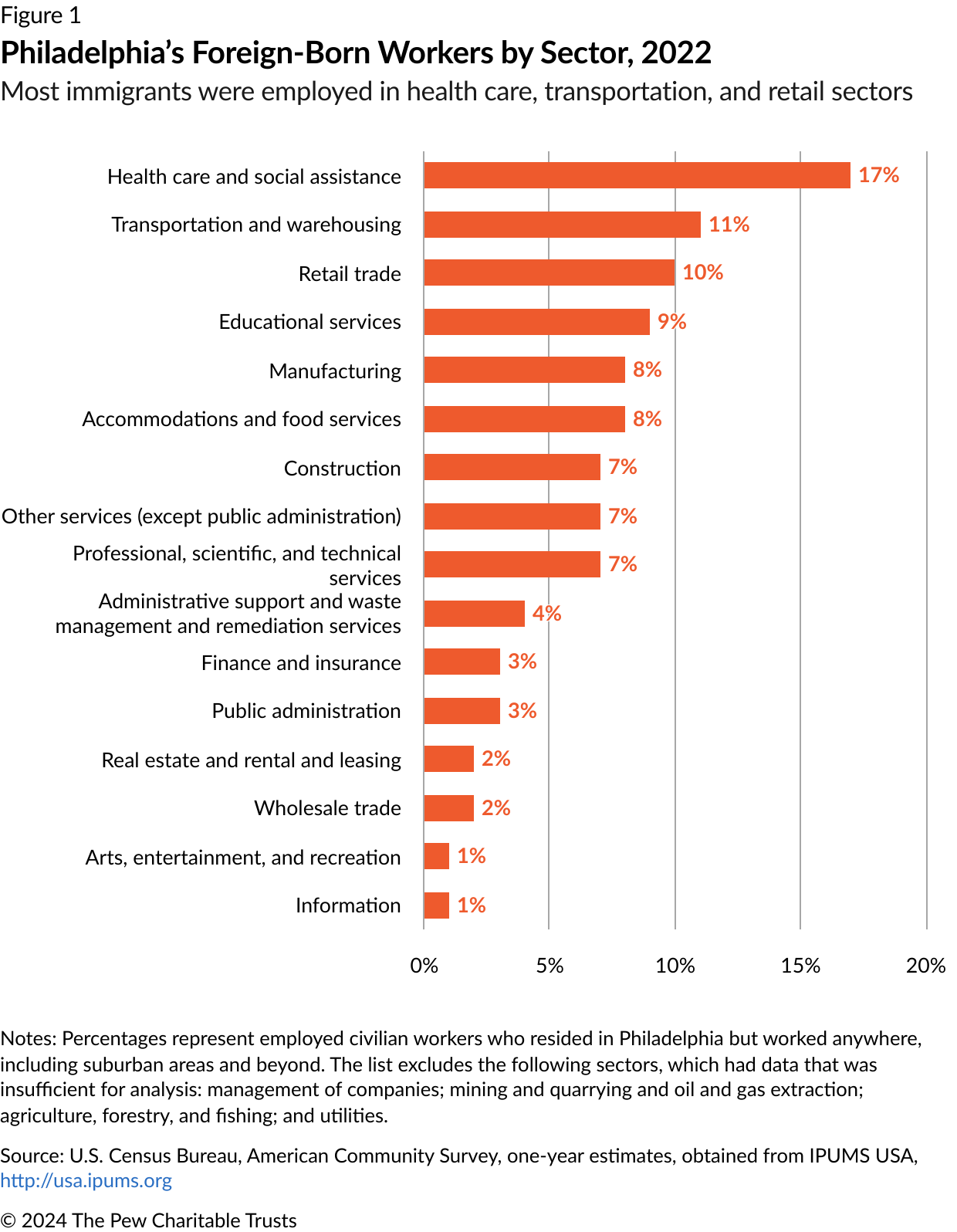

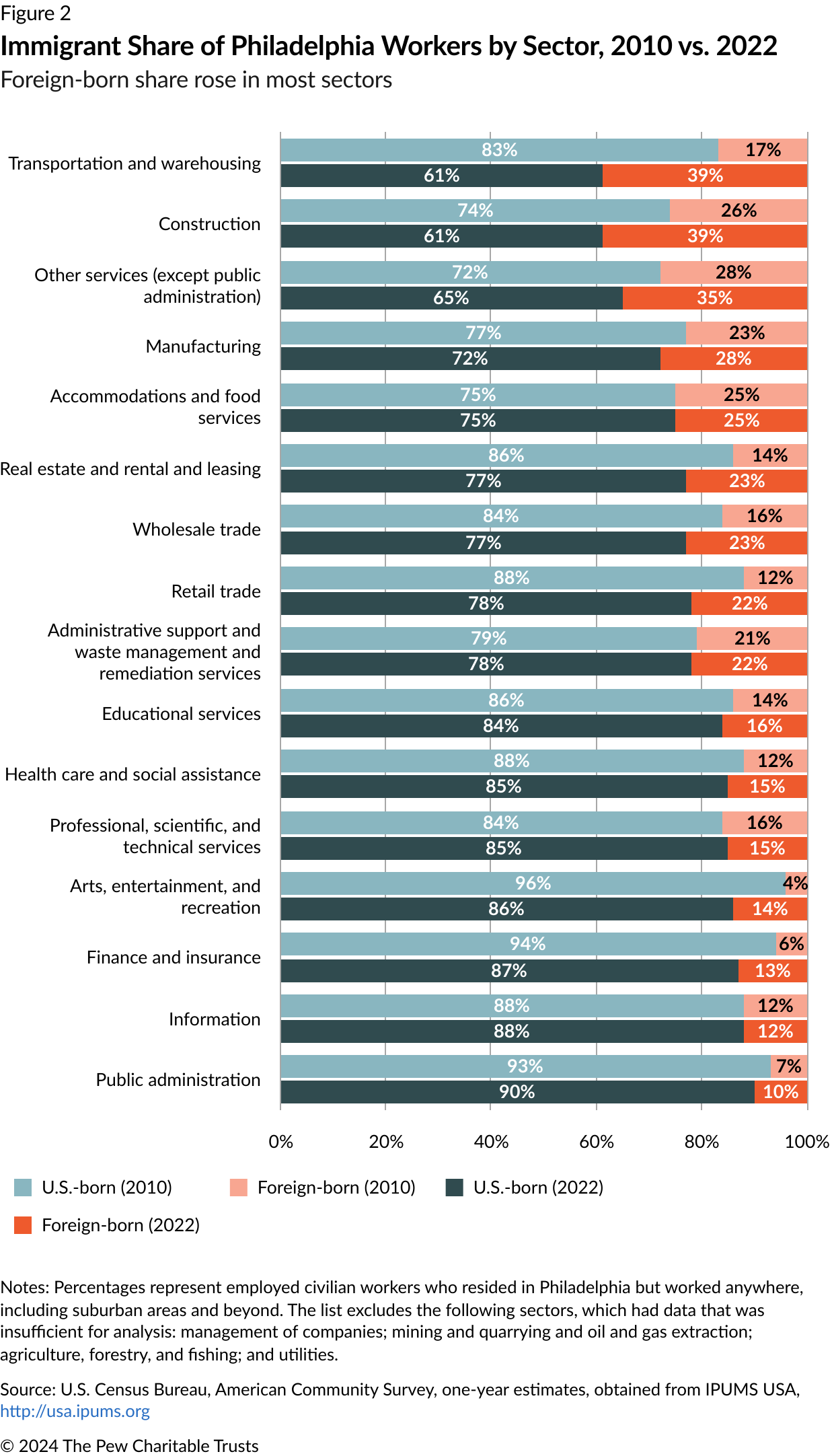

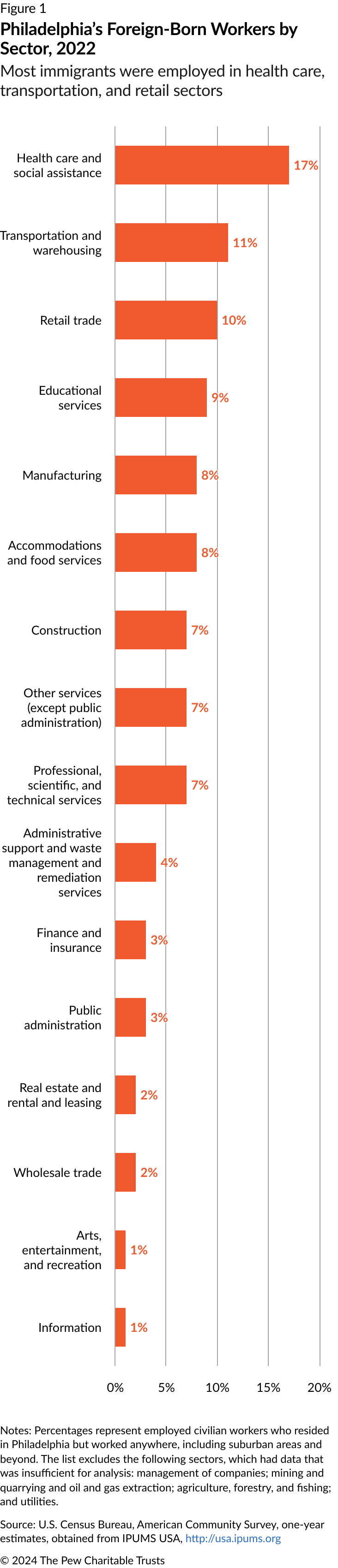

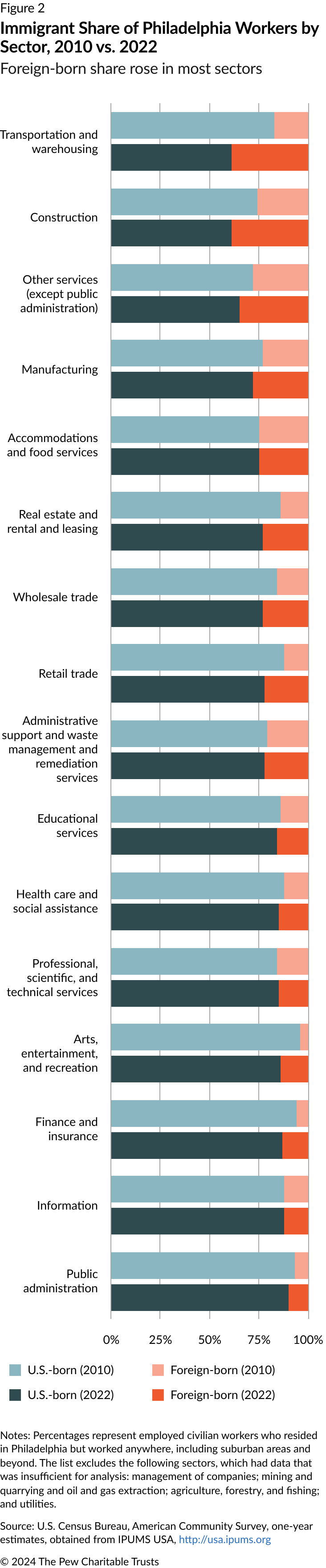

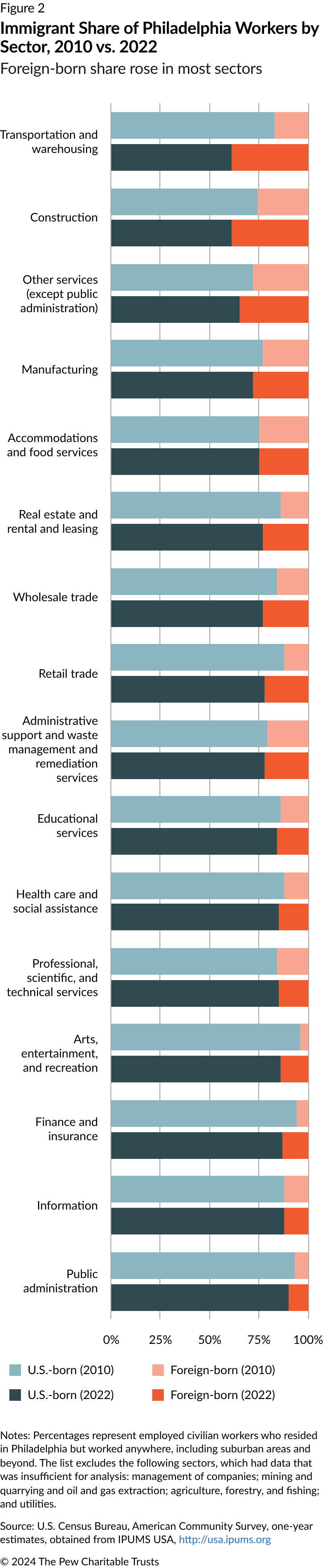

As of 2022, around 20% of employed Philadelphia residents were immigrants, more of whom were of prime working age (ages 25-54) than U.S.-born residents. Most had jobs in the health care and social assistance sector, and the fewest were employed in the wholesale trade; arts, entertainment, and recreation; and information sectors. (See Figure 1.) Philadelphia immigrants were particularly important to the region’s transportation and warehousing, construction, and other consumer services sectors, where they represented at least a third of all workers. (See Figure 2.) In construction, for example, they accounted for 77% of employment growth from 2010 to 2022. Those industries include many jobs that don’t require prior skills, college degrees, or English proficiency, as well as many that a majority of U.S.-born residents say they don’t want to fill, according to a Pew Research Center survey.

Investing in homes and businesses

Owning a home is not just the American Dream; it’s a tried-and-true way for immigrants to stoke the local economy and their own financial security. In the 2018-22 period, immigrants or their spouses represented 21% of all owner-occupants in Philadelphia, according to census data, exceeding their share of the population and signaling a desire to put down roots in the city. The share of immigrants who were owner-occupants was nearly the same as for U.S.-born residents: 51%. (Immigrants’ housing patterns and households are explored in other parts of this series.)

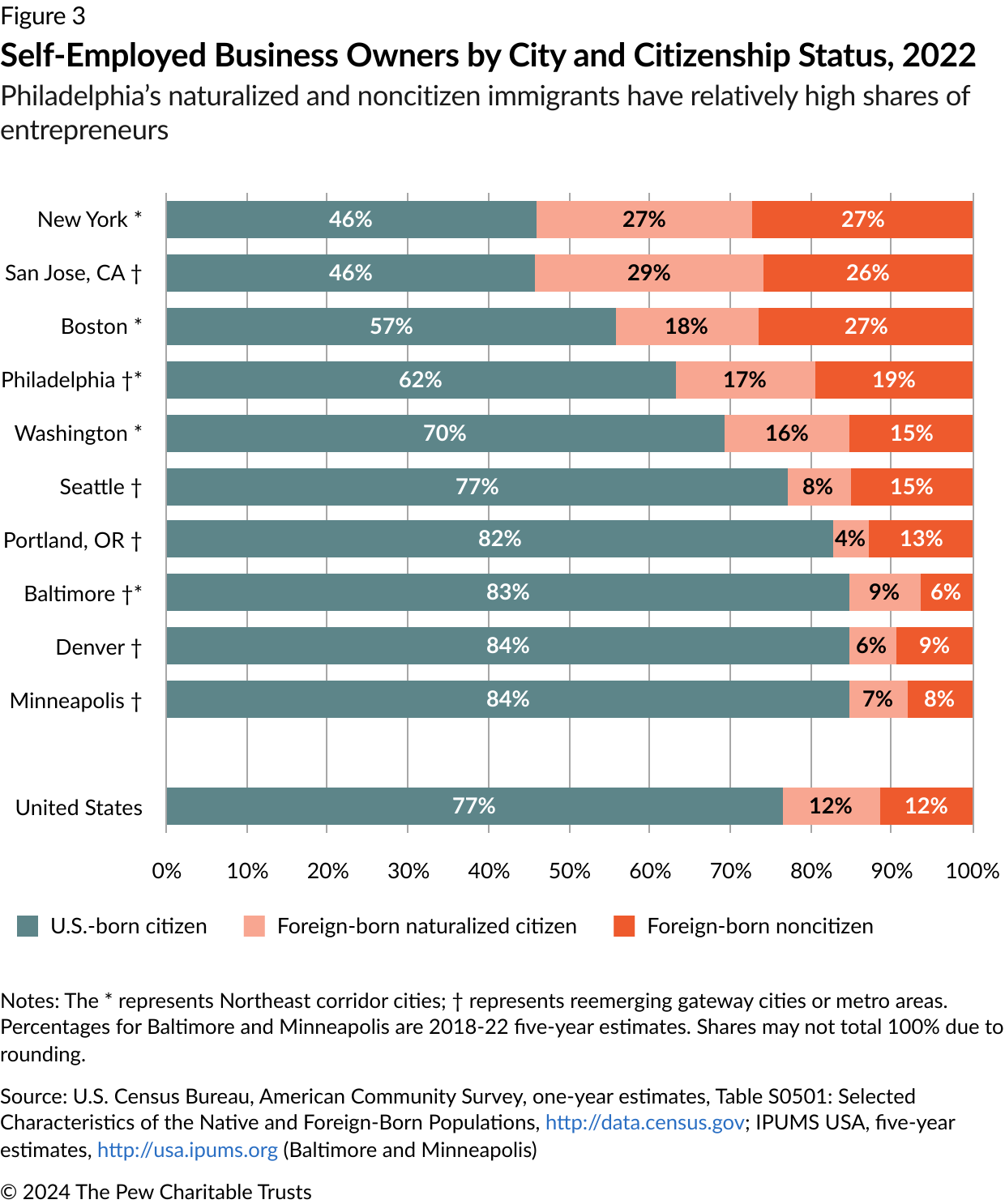

Philadelphia’s immigrants also stood out as entrepreneurs: In 2022, they accounted for 36% of the city’s 41,000 self-employed owners of unincorporated businesses (generally meaning “mom and pop” firms, usually sole proprietorships with just a few workers and located in neighborhood corridors, although not counting startup corporations). That was double their overall share of the population and higher than in many comparison cities. (See Figure 3.) Around half were noncitizens, some of whom may have gone into business because they lacked work authorization or had foreign college or professional credentials that were unrecognized in the United States. Whatever the reason, immigrant entrepreneurs play an outsize role in neighborhood commercial corridors and small businesses, which have been an underperforming pillar of Philadelphia’s economy.

Earnings mostly low, some high

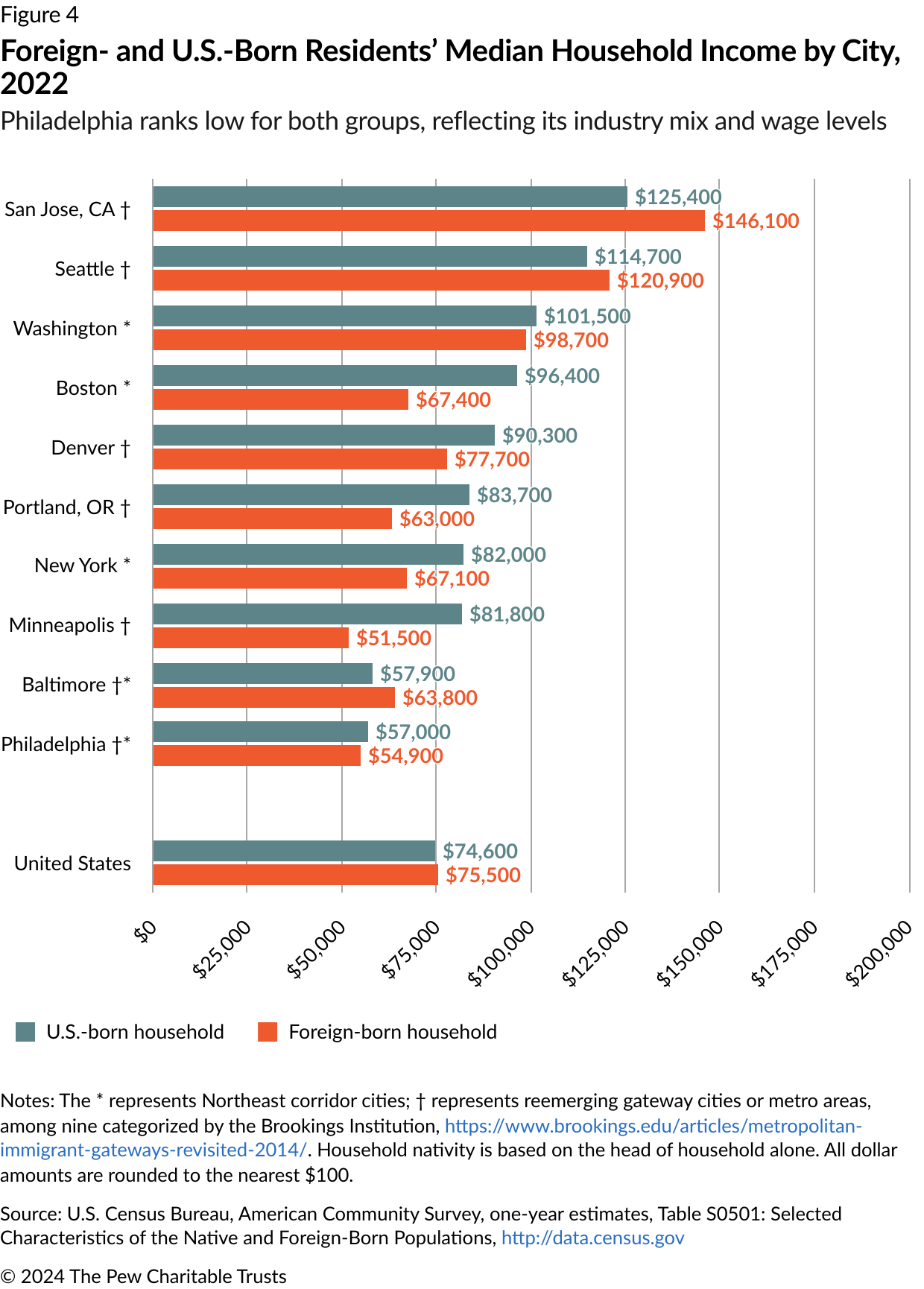

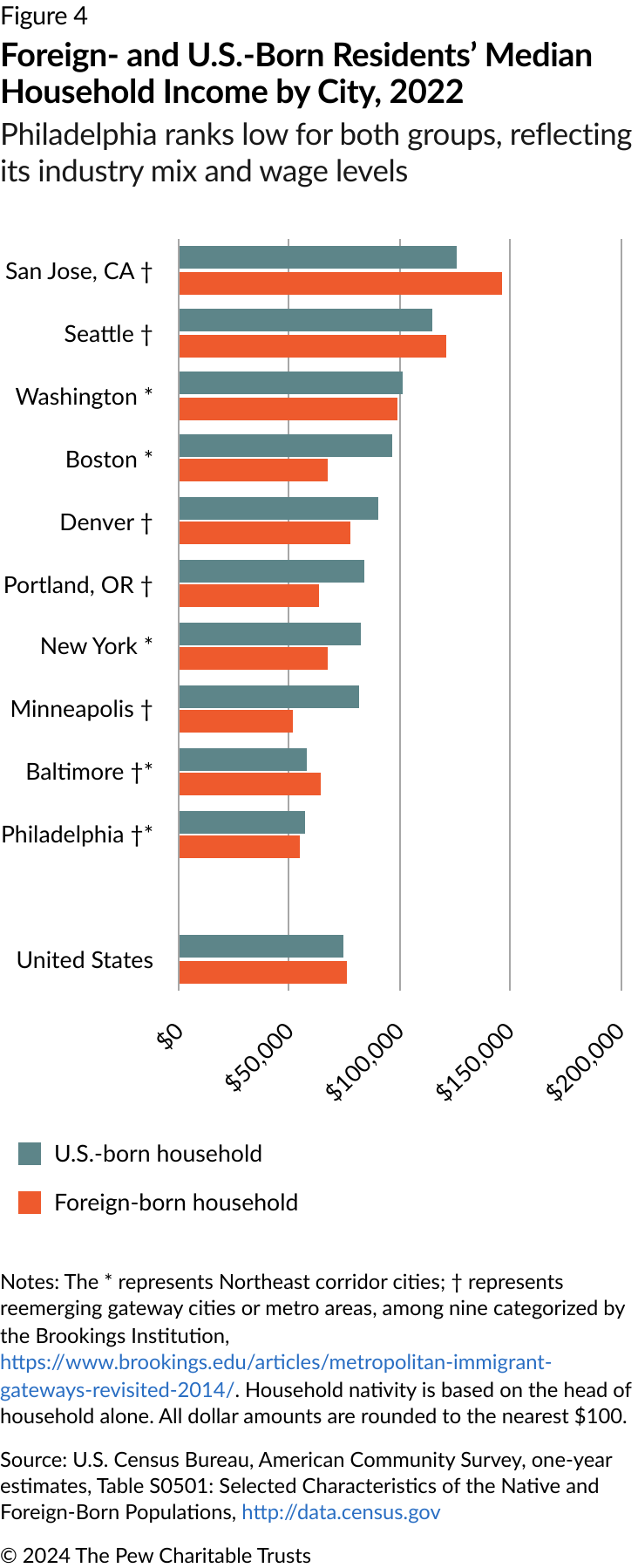

Either as workers or as business owners, immigrants in Philadelphia, as a group, earned less than immigrants in the comparison cities and the country as a whole, with a median household income of $54,900 in 2022. Their low incomes were on par with Philadelphia’s U.S.-born residents, who also have relatively low incomes, driven by many factors, including the lower cost of living and the mix of industries and jobs compared with other big cities. (See Figure 4.)

Consequently, many immigrants live in poverty. Although their poverty rate declined from 2010 to 2022 (from 24.7% to 19.6%), similarly to the U.S.-born rate (from 27% in 2010 to 22.1% in 2022), immigrants’ rising share of Philadelphia’s overall population has also left them with a bigger share of the city’s poor population: 14.5% in 2022, up from 11% in 2010. Immigrants’ poverty rate in 2022 was also above most comparison cities’ rates.

At the other end of the spectrum are highly skilled, high-earning immigrants. Around a quarter of foreign-born Philadelphians earned $75,000 or more in the 2018-22 period. One source of these workers has been Philadelphia’s major universities, which host thousands of international students and researchers each year on temporary visas and, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, are among the top producers of tech entrepreneurs. Federal data for 2006 to 2017, analyzed by Econsult Solutions Inc. for Campus Philly, shows the Philadelphia metro region has benefited but at a lower rate than other regions: An average 25% of Philadelphia-area graduates chose to stay in the region on a special temporary visa extension, known as optional practical training, below the average 34% in the comparison metro areas. That retention rate, representing an average of 200 individuals per year over the 2006-17 period, reflects the Philadelphia area’s mix of available jobs and degrees granted, as well as its allure and job prospects compared with other cities. It does not include international graduates who may have come to Philadelphia from other metro areas.

Local taxes

Most city residents—immigrants or natives—rely on tax-funded services and infrastructure like streets and schools, police and fire, and in some cases support programs for low-income residents. Parsing the usage by foreign- or U.S.-born residents was beyond the scope of this analysis. But it was possible from census data to make a rough estimate of each group’s share of the city’s wage tax (wage and salary income), school income tax (interest, dividend, and rental income), property tax (residential real estate value), and net profits tax (self-employed business owners’ business income).

Immigrants would owe those taxes just like U.S.-born residents do, regardless of their legal status; noncitizens and unauthorized immigrants who lack a Social Security number may pay tax using an individual tax identification number.

Census data shows that immigrants’ share of all wage and salary income in Philadelphia in the 2018-22 period was about 17%, which could approximate their share of the city’s wage tax. Immigrants accounted for around 5% of interest, dividend, and rental income reported by all city residents, which could be similar to their share of the school income tax. They accounted for 23% of personal earnings from a business, which may approximate their share of the city’s net profits tax on self-employed owners. And their share of residential property taxes was around 15%, based on a census question asking all households how much property tax they paid in the previous year. (See methodology for details.) These estimates do not take into account tax exemptions, nonresident income, or unreported income.

Philadelphia’s growing immigrant population has given the city’s economy and public finances a significant boost, reflected in the jobs they fill, the homes they buy, the businesses they create, and the taxes they pay. At the same time, additional costs come with integrating many people with different languages, skills, and cultures.

Learn more about the demographics of foreign-born workers and entrepreneurs, and read other installments in this series about immigrants’ countries of origin and how they are diversifying Philadelphia.

Thomas Ginsberg is a senior officer and Maridarlyn Gonzalez is a senior associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Philadelphia research and policy initiative.