40 Years of Investment in Innovative Science

In this Issue:

- Winter 2025 View All Other Issues

- 40 Years of Investment in Innovative Science

- Looking Back on a Year of Milestones

- How U.S. Public Opinion Has Changed in 20 Years

- Finding Answers

- Two Decades Supporting the Arts in the Philadelphia Region

- Racial Inequities in Student Loan Repayment

- Americans Feel Good About Job Security—But Not Pay

- COVID-19’s Effects on Philadelphia’s Wage and Earnings

- ’Heights Philadelphia’ Prepares for College and Career

- The Silly Rule That’s Helping Keep Housing Costs High

- How Some Weather-Related Disasters Increase Risk of Others

- Return on Investment

- Many Americans Perceive a Rise in Dangerous Driving

- View All Other Issues

Four Decades of Investment in Innovative Science. By Karen Hopkin

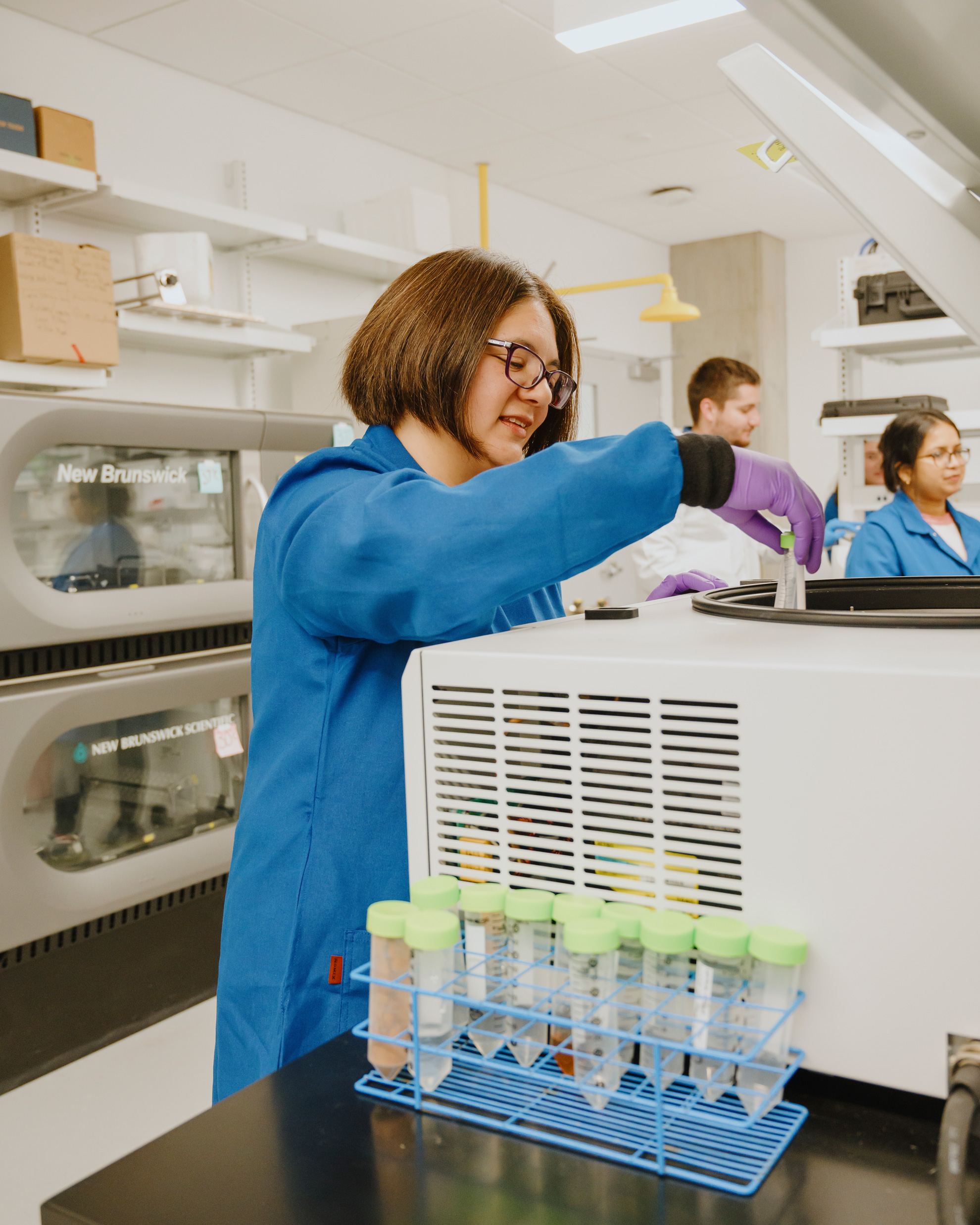

Pew biomedical scholars’ cutting-edge research helps advance science and public health

When David Mendoza-Cózatl, a 2006 Pew Latin American fellow in the biomedical sciences, got an email soliciting applications for the Pew Innovation Fund, he sprang into action. The program provides alumni from any of the Pew biomedical programs with funding to pursue collaborative, intensely interdisciplinary projects. Mendoza-Cózatl was hoping to explore the relationships that plants establish with bacterial communities—interactions that can benefit both parties. “My expertise is in plant biology,” he says. “But I know nothing about bacteria. So, I went to the Pew website and asked: Who works with the microbiome?”

Clarissa Nobile’s name came up, and Mendoza-Cózatl sent her a note. “I’ve always wanted to get more into the agricultural side of things,” says Nobile of the University of California, Merced, a Pew biomedical scholar from 2015. “So, I thought, why not?”

“That’s the power of Pew,” says Mendoza-Cózatl. “All it took was one email to establish our collaboration.” A few Zoom meetings later, the pair had refined their proposal, which focuses on how bacteria can facilitate a plant’s iron uptake. About 30% of the world’s population is iron deficient, so coming up with ways to enhance iron levels in crops “could be an agricultural game changer,” says Nobile. Pew agreed and awarded the pair an Innovation Fund grant in 2022.

This partnership is just one example of the collaborative and cooperative spirit that continues to thrive as the Pew biomedical programs celebrate a major anniversary: It’s been 40 years since the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences was founded in 1985. In that time, the program, the first in the organization’s history to carry the Pew name, has supported more than 800 outstanding young researchers, many of whom have gone on to receive major scientific awards, including six Nobel Prizes. In the ensuing years, Pew’s biomedical programs continued to grow, expanding to include the Pew Latin American Fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences, which launched in 1991. In 2014 Pew and the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust partnered to launch the Pew-Stewart Scholars Program for Cancer Research. Three years later, in 2017, the Pew Innovation Fund began.

All of these programs bring together cohorts of talented early-career scientists—assistant professors in the case of scholars and postdocs in the case of fellows—and provide them with significant funding over two to four years. In addition, the programs bring these participants together for an intensive week of science and socializing every year. By doing so, The Pew Charitable Trusts not only supports promising young investigators at a critical juncture in their academic journeys, but also cultivates relationships, mentorships, and collaboration and exposes participants to a broad range of innovative ideas designed to ignite their curiosity and trigger rewarding new avenues of research. Those efforts ultimately deepen understanding of biological systems and pave the way toward improving human health.

“It’s the most impactful and meaningful philanthropic life sciences programs I’ve ever worked with,” says Craig Mello of the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, former National Advisory Committee chair to the program and a 1995 biomedical scholar. “It instills the importance of sharing ideas and reinforces the philosophy that the mission of science is to benefit humanity and make a positive impact on the world.”

The trick lies in supporting cohorts of imaginative, interdisciplinary individuals who are pioneers and leaders in their fields. “Over the past four decades, Pew has provided funding for the sorts of high-risk, high-reward projects that early-career faculty don’t typically have the luxury to carry out,” says Ana-Rita Mayol, the director of Pew’s biomedical programs. “This investment has helped to advance cutting-edge and award-winning science that’s made a real difference in people’s lives. And it has supported scientists who are community-minded and collaborative.”

Going the extra mile to bring these investigators together each year lays the groundwork for them to make enduring professional and personal connections. “Pew creates a real cohort, a real community that continues even after you leave,” says Lee Niswander of the University of Colorado, Boulder, a 1995 biomedical scholar who took over for Mello as chair in 2024. Attending the meetings, she says, “opens up amazing intersections that you wouldn’t establish otherwise.” Such novel combinations can give rise to truly groundbreaking research.

Pew’s investment in each of its individual grantees is life-changing from the start. “When you have an organization as prestigious as Pew say, ‘We think your work is worthy of being recognized,’ it gives you the confidence to tackle difficult projects that other people are telling you are too risky,” says Song Tan of Pennsylvania State University, a 2001 biomedical scholar.

And the added funding (anywhere from $130,000 to $300,000 over the course of the grants) certainly helps. “At that point in my career, I didn’t have any grants for the work on RNA interference,” says Mello, who went on to win a Nobel Prize for discovering this process, commonly called RNAi, which has since been developed into a tool for selectively blocking the activity of target genes. “It was just too totally off the map. So, Pew had a huge impact on my science—and on the whole RNAi field.”

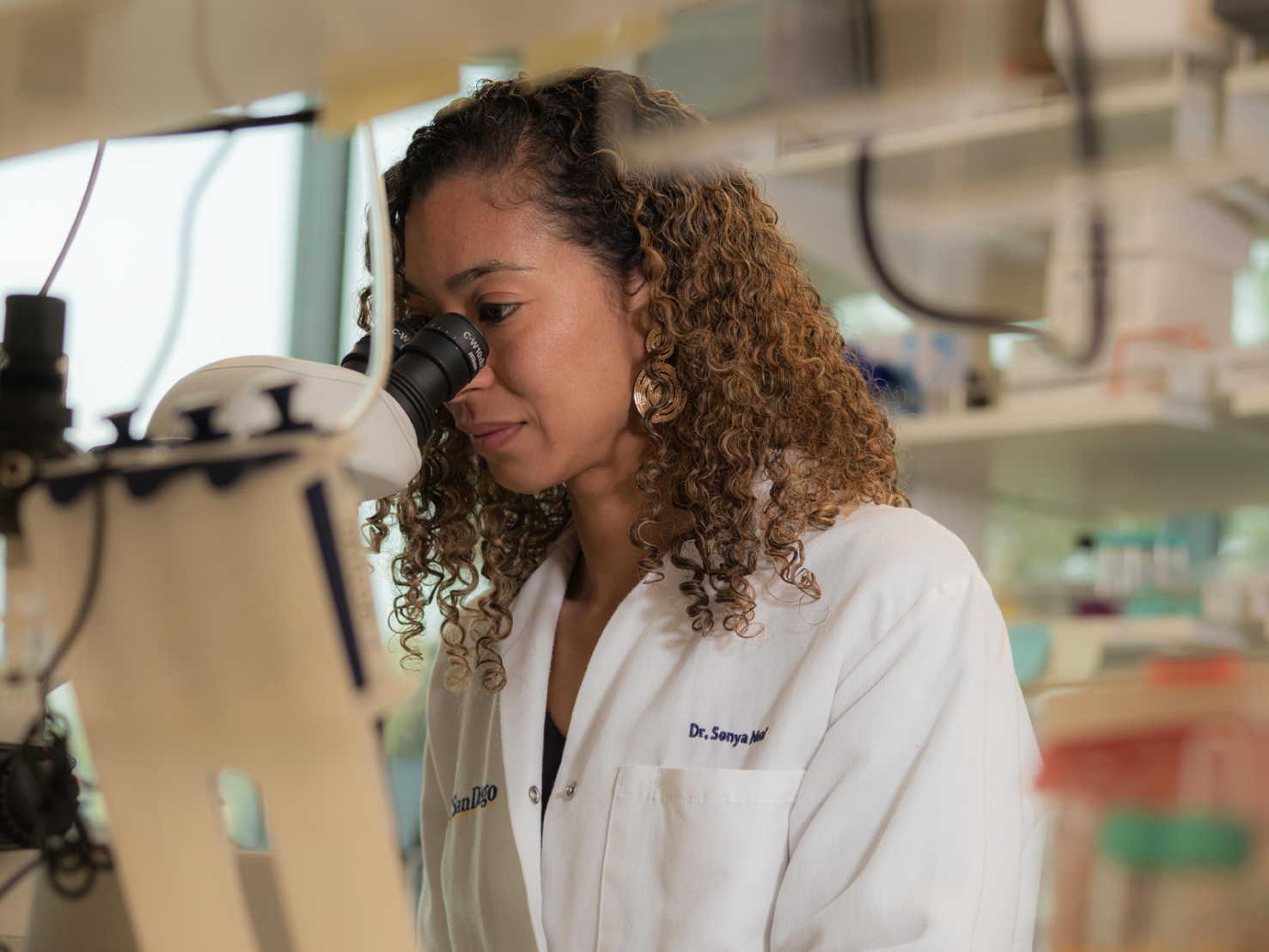

Receiving a Pew scholarship also boosts grantees’ visibility at a time when making connections is crucial. “I got five invitations to give seminars that first year alone,” says Sonya Neal of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), a 2020 biomedical scholar. “Once you start giving these talks, it’s like a domino effect that just explodes to the point where everyone knows about your work.”

Receiving a Pew scholarship also boosts grantees’ visibility at a time when making connections is crucial. “I got five invitations to give seminars that first year alone,” says Sonya Neal of the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), a 2020 biomedical scholar. “Once you start giving these talks, it’s like a domino effect that just explodes to the point where everyone knows about your work.”

Some of those seminar invites come from fellow scholars. “We see each other at conferences, follow each other on social media, track each other’s careers, and cheer for each other’s successes,” says UCSD’s Kim Cooper, a 2015 biomedical scholar and Innovation Fund investigator. “I deeply respect and appreciate the Pew program for the community it builds.”

A large part of that community-building takes place at Pew’s annual gatherings. These meetings provide a healthy mix of intellectual engagement and outdoor adventure, a structure that encourages the scholars and fellows to get to know one another socially, outside of an academic setting. “The Pew meetings are the best I’ve ever been to,” says Nuo Li of Duke University, a 2018 biomedical scholar who also has an Innovation Fund grant. In addition to hearing about an incredibly broad swath of biomedical science from investigators at the top of their fields, Li valued the opportunity to exchange ideas and get advice about how to manage a successful lab. At one meeting, Li says, “I remember kayaking through the Florida mangroves with Jesse Goldberg.” As a 2014 biomedical scholar, Goldberg was a few years ahead of Li in his career trajectory and was able to offer assurance and suggestions for navigating regulatory hurdles and other setbacks. “It helped me put things into perspective,” says Li. “I left the meeting refreshed and invigorated and excited to focus on my science.”

But most importantly, the breadth of the scholars’ and fellows’ collective expertise guarantees exposure to a range of exciting new ideas and technologies. “That inspires me to apply more novel, cutting-edge techniques to our work,” says Christina Towers of the Salk Institute for Biological Studies (a 2022 Pew-Stewart scholar). At a recent meeting, Towers, who studies cancer cell metabolism, was encouraged by the neuroscientists in her cohort to try using optogenetics—a popular method for controlling the activity of nerve cells—to manipulate the metabolic reactions of cancer cells in mice. “It was definitely outside my wheelhouse,” she said. “But talking to the neurobiologists made me feel like it was within reach, so now my lab is developing this tool to pursue a new set of interesting biological questions.”

Scholars also bring a range of ideas and experiences from a broad swath of institutions. “Pew values diversity in their programs,” says Nobile, who was the first Pew biomedical scholar at the University of California, Merced, the newest institution in the UC system, where nearly three-quarters of the students are the first in their family to attend college. “Going to Pew meetings and interacting with people from a variety of backgrounds in terms of experience, expertise, fields, different kinds of institutions, and different countries has really been transformative.”

Sitting in on talks from wide-ranging and unfamiliar fields can definitely get the creative juices flowing. Roozbeh Kiani, who studies systems neuroscience at New York University (biomedical scholars class of 2016), was transported by a presentation on modeling the spread of the Zika virus. “Looking at those slides, I thought, ‘Forget about the countries, forget about the map, just focus on those lines connecting one node to another,’” he says. “They reminded me of the complex neural networks that make up the human brain.” Inspired by that unexpected flash of insight, Kiani developed a statistical method for deducing the architecture of a neural network based on the activity of just one of its constituent neurons—information that could someday be used to manipulate a network’s activity to, say, replace painful memories, alter perceptions, or reduce the damage caused by a stroke. Being able to make that kind of intellectual leap, from tracking pandemics to tracing neural networks, is something that Kiani says “pretty much happens only at Pew meetings.”

In addition to novel intellectual connections, Pew meetings foster personal connections that lead to fruitful collaboration. Based on the relationship they built at Pew meetings, Kiani and Li have elected to pool their resources and expertise to examine the neural mechanisms that allow monkeys and mice to make decisions—and change their minds. By identifying mechanisms that apply across this evolutionary span, Li says their project, which is supported by an Innovation Fund grant, could yield findings that are relevant to the workings of the human mind. “I wouldn’t have seen this coming when I started my lab eight years ago,” says Li. “Pew has certainly shaped the trajectory of my research and given my work more purpose.”

Tan agrees with the importance of cultivating relationships. “The camaraderie and trust you build at Pew meetings is key to collaboration,” he says. Almost two decades after they met, Tan launched a joint project with Cheng-Ming Chiang (a 1996 biomedical scholar and currently a member of the advisory committee). Chiang studies BRD4, a protein that plays a key role in gene regulation in both normal cells and cancer cells. He has been working on finding small molecules that will disrupt BRD4’s interaction with cancer-promoting proteins without compromising its ability to bind to chromosomal DNA, or chromatin, and to regulate the activity of normal genes. That’s where Tan comes in.

Tan’s specialty is determining the structures of large complexes of gene-regulatory proteins with chromatin. He’s attempting to show how BRD4 binds to chromatin and other proteins. Figuring out how to selectively disrupt specific BRD4 interactions could hold the key to developing targeted cancer therapeutics with fewer side effects.

“I have been talking to structural biologists for the past five or six years,” says Chiang. “And nobody wanted to collaborate, because they thought the project was too risky.” Although the BRD4 study is not currently funded by Pew, it’s exactly the type of work Pew typically supports. “They encourage unconventional thinking, and they like to see proposals that are high risk and high impact,” says Chiang.

To pursue such projects, scholars team up with other scholars, fellows, and even the advisors. “My lab is highly collaborative,” says Neal. “I’m always looking for new technologies to apply to our model systems because we’re a question-driven lab, and I feel like a diversity of approaches helps us move forward.” And the Pew meetings are ripe with opportunity. “I have no shame,” laughs Neal. “When I hear about an exciting new technology, I just run up to that person and say, ‘Oh my gosh, can we talk more about how I can adopt this in my lab?’ It just inspires me to innovate.”

Neal recently teamed up with Towers to develop techniques that will allow her to explore how the proteins she studies fuel the progression of pancreatic cancer. “Knowing exactly how this works could provide new therapeutic targets for pancreatic cancer,” says Neal, who bonded with Towers over lunch at a Pew meeting. The two decided, then and there, to join forces. “It’s funny because we work right across the street from each other,” says Towers. “But we had never had a conversation about our science. The Pew meeting was the catalyst.”

Meanwhile, just down the hall at UCSD, Cooper had been talking with Elizabeth Villa, a 2017 biomedical scholar, about taking a closer look inside chondrocytes, bone-building cells that swell up to 20 times their original size. Cooper was certain that Villa’s skills with microscopy could shed light on how they achieve this remarkable feat, and also thought the project seemed a natural fit for an Innovation Fund grant. “But the Innovation Fund is limited to Pew alumni, so we had to wait for Elizabeth to ‘graduate’ to apply,” says Cooper.

When Villa texted her to say they’d gotten the grant, Cooper replied with a celebratory string of emojis and tears in her eyes. “This came through at a time when I really needed a win,” she says. Midcareer can be particularly challenging, because investigators are no longer eligible to apply for early-career support. “Knowing that people at Pew still believed in my ideas—not just at the beginning but through the arc of my career—that meant a lot,” she says.

“The Innovation Fund is a way for our grantees to rekindle connections with each other, and for Pew to reinvest in them,” says Mayol. And grantees take that investment seriously. “Because Pew has given us so much, I think a lot of us come out wanting to give back to Pew,” says Neal. Former scholars recommend other scholars and fellows for faculty positions, volunteer for the program’s advisory committee, and continue to support the program by nominating outstanding candidates—year after year. “I’m trying to be a Pew superspreader and everyone knows it,” laughs Neal.

And of course they continue to carry out the sort of science that Pew first encouraged them to do. “Although I had Pew funding several decades ago, it still influences what I do today,” says Tan. “Pew makes you want to be a better scientist and tackle problems that have true impact. I am so grateful to be part of the Pew family.”

Karen Hopkin is a longtime science writer based in Boston.

A Brief History of The Pew Biomedical Programs

Since 1985, when the Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences announced its first class of innovative scientists, the program has supported groundbreaking research by early-career scientists working to improve human health. Today, Pew’s biomedical programs offer awards through three different program branches and an Innovation Fund. Over the course of 40 years, the community of scholars and fellows participating in Pew’s programs have won an array of prestigious honors— there have been six Nobel Prize winners, five Lasker Award recipients, 12 MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship awardees, and two Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences winners, among others.

1985: Pew selects its first class of biomedical scholars

The Pew Scholars Program in the Biomedical Sciences awarded funding to its first class of 19 scientists in 1985. The following year, the program held its first annual meeting in Phoenix—and each year since, it has brought together members of Pew’s scientific community.

1991: Pew awards its first class of Latin American fellows

Early Pew scholars, all working in the United States, recognized the opportunity to expand their community and support science beyond this country’s borders. This led to the development of the Pew Latin American Fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences, which debuted in 1991 and funds talented scientists from Latin America for two years of postdoctoral training in the United States. Nearly 70 percent of fellows accept additional funding and return to their home country to establish their own labs.

2014: Launch of the Pew-Stewart Scholars Program for Cancer Research

Pew partnered with the Alexander and Margaret Stewart Trust to launch the Pew-Stewart Scholars Program for Cancer Research in 2014 to support early-career scientists seeking to uncover treatments and cures for cancer.

2017: Pew creates the Innovation Fund

As a vote of confidence in the power of collaborative, interdisciplinary research, Pew created the Innovation Fund in 2017 to encourage partnerships among alumni of Pew’s biomedical programs. Each year, pairs of researchers are selected as Innovation Fund investigators; they receive $270,000 over three years for joint research projects.

Noteworthy

Pew Scholar Uses New Technology to Study Preeclampsia

Trust in Science: From Lab to Life

In this episode, Pew Research Center’s Alec Tyson analyzes the latest polling on trust in science, while Donna Dang and Rebecca Goldburg from The Pew Charitable Trusts discuss the importance of conservation and biomedical research to improve the health of our planet and communities.