Public Safety Aspects of the Heroin Abuse Epidemic

Overview

Policymakers at all levels of government are attempting to address a nationwide increase in heroin abuse.1 Use of the drug has tripled over the past decade, paralleling widespread misuse of prescription opioids, and overdose deaths have increased nearly threefold in the past seven years.

Available research suggests that the most effective response to the growth in heroin abuse is a combination of law enforcement to curtail trafficking and limit the emergence of new markets; alternative sentencing to divert nonviolent drug offenders from costly incarceration; treatment to reduce dependency and recidivism; and prevention efforts that can help identify individuals at high risk for addiction. These strategies are most effective when tailored to the specific nature of the heroin problem in a given community. Research further suggests that increasing criminal penalties for heroin-related offenses is unlikely to reverse the growth in heroin use and tends to have a poor return on investment.

Heroin supply on the rise

Between 2007 and 2013, heroin seizures by federal, state, and local law enforcement increased 289 percent.2 (See Figure 1.) U.S. authorities attribute the increase to rising production in and trafficking from Mexico, which is probably related to a decline in marijuana prices that has made the manufacture of heroin more profitable.3 Mexico recently surpassed Colombia as the largest supplier of heroin to the United States; the two countries now provide more than 90 percent of the heroin in the United States.4

What Is Heroin?

Heroin is a highly addictive illegal drug derived from morphine, a naturally occurring opiate found in poppies primarily grown in four locations: Southeast Asia, Southwest Asia, Mexico, and Colombia.* Heroin’s effects are similar to those of prescription opioids, such as oxycodone, codeine, methadone, and fentanyl. Like many other chemical dependencies, heroin addiction is a chronic, relapsing brain disease with a wide range of medical consequences and severe withdrawal symptoms.†

*The term opiate refers to naturally occurring substances. The term opioid refers to synthetic and semisynthetic substances. Source: Drug Enforcement Administration, “Drug Fact Sheet: Heroin,” http://www.dea.gov/druginfo/drug_data_sheets/Heroin.pdf.

†U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, “Heroin Addiction” (October 2010), 2, http://www.report.nih.gov/NIHfactsheets/ViewFactSheet.aspx?csid=123.

Heroin use: Rare but increasing

Although less than 1 percent of Americans 12 and older—an estimated 681,000 people—have used heroin within the past year, the rate has tripled during the past decade, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.5

Heroin dependence also appears to be growing, with addiction to the drug making up 7.5 percent of all substance use disorders in 2013, up from 2.8 percent in 2003.6 (See Figure 2.) Nearly two-thirds of those who have used heroin in the past year say they are dependent on it—a much higher proportion than is found among users of cocaine, marijuana, hallucinogens, and other illicit drugs.7

One possible reason for the rise in heroin abuse is the drug’s connection with prescription opioids, which are abused much more widely. Nearly 80 percent of heroin users say they previously abused prescription opioids.8 For many users, changes in the prescription opioid market may have facilitated the transition to heroin. One study found that dependent opioid users were almost twice as likely to turn to heroin after one widely misused opioid brand, OxyContin, was reformulated in 2010 to reduce abuse by making the tablets more difficult to crush.9 In addition, heroin is cheaper and easier to obtain in some communities than black-market prescription opioids.10

Heroin use is prevalent among those entering prisons and jails

Incarcerated offenders are far more likely than the general population to have a history of heroin use. Approximately 8 percent of state prisoners and 6 percent of federal inmates reported using heroin or other opiates in the month before their offenses, according to U.S. Justice Department data from 2004 (the most recent year for which statistics are available).11 By comparison, 0.1 and 1.8 percent of the general population reported using heroin or opiates, respectively, within the past month that year.12

Heroin and opiate use among criminal offenders varies significantly by location. Data from the Office of National Drug Control Policy illustrate a declining trend in heroin use over the past decade among those arrested in Chicago and New York, while use has increased in Denver and Sacramento over the same period.13 This variance is probably due to drug market dynamics that change based on supply, demand, and other forces, such as prevention efforts.14

Heroin deaths have spiked in recent years

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 8,000 people died as a result of an unintentional heroin overdose in 2013, a 182 percent increase from 2008.15 During the same span, unintentional overdose deaths from prescription painkillers rose 13 percent, from 11,882 to 13,486.

Policy interventions

The heroin epidemic is not confined to a particular state or region: Between 2000 and 2009, 45 states reported public safety, health, and economic harm stemming from heroin use, according to an index developed by the Office of National Drug Control Policy.16 In response, state and federal policymakers have sought to address the problem through a variety of strategies.

Task forces

At least 15 states have task forces, made up of state lawmakers, police officials, and community leaders, directly focused on heroin abuse.17 The recommendations from these task forces often include allocating more funds to support prevention, expanding access to treatment, and enhancing criminal penalties for the possession, sale, and trafficking of heroin and opioids.

Legislative action

According to the Network for Public Health Law, at least 24 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws that expand the availability and permit the use of naloxone, a prescription drug shown to counter the effects of a heroin overdose.18 These policies typically allow medical professionals to prescribe naloxone while allowing nonmedical professionals, such as treatment counselors, to acquire it for use in emergencies.

Additionally, at least 21 states and the District have provided legal protections for good Samaritans who alert medical professionals to heroin and other drug overdoses even if they are using illegal drugs themselves.19

Some states have also sought to boost criminal penalties for heroin distribution. Louisiana, for example, enacted a law in 2014 that doubles the mandatory minimum prison sentence for heroin distribution from five to 10 years.20 However, most recent state proposals to boost heroin penalties have not become law. Illinois and Vermont were among the states that considered such proposals but ultimately declined to increase sentences for heroin offenses in 2014.21

Between 2007 and 2013, heroin seizures by federal, state, and local law enforcement increased 289 percent.

Federal involvement

In August 2014, then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder instructed federal law enforcement agencies to equip medical personnel and others with naloxone to address what he called the “public health crisis” of heroin and prescription opioid overdose.22 To support this effort, the Bureau of Justice Assistance developed a toolkit to provide information to law enforcement agencies establishing naloxone programs.23 Congress has also considered a variety of proposals to respond to rising heroin abuse, including bipartisan legislation that would, among other steps, expand youth education efforts, improve first responders’ access to naloxone, and create an evidence-based treatment and intervention initiative.24

Considerations for effective policy

Research suggests that a combination of targeted law enforcement, alternative sentencing, treatment, and prevention offers the best overall approach to reducing the use and consequences of heroin and other drugs. Using focused strategies to address heroin markets within specific communities or states can have dramatic effects. For example, if a heroin market is emerging, certain law enforcement tactics can prevent it from establishing a foothold. If a market is already established, prevention, harm reduction, and evidence-based sentencing strategies may provide a more effective response.

Nearly 80 percent of heroin users say they previously abused prescription opioids.

Law enforcement strategies. A 2014 report by the Police Executive Research Forum found that law enforcement agencies in several states are collaborating with other stakeholders to develop proactive approaches, such as diverting some offenders with substance use disorders into treatment.25 Another model involves the use of harm-reduction strategies, such as training law enforcement officers in overdose prevention, investing in community policing in neighborhoods with emerging heroin markets, and targeting particularly problematic dealers.26 Drug market interventions include dismantling open-air street markets through police collaboration with community organizations—a strategy that directly targets drug dealers, making clear that they face a heightened risk of punishment if they continue to distribute illicit drugs. This approach has been used in communities across the country, including Boston; High Point, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; Rockford, Illinois; New Orleans; and Flint, Michigan.27

Alternative sentencing strategies. States are increasingly turning to sentencing and corrections options tailored for drug offenders in lieu of long stays behind bars. Drug courts employ a combination of intensive supervision and treatment that supports sobriety, recovery, and reduced recidivism. A recent systematic review of drug courts operating in 30 states found that the combination of comprehensive services and individualized care is an effective way to treat offenders with serious addictions.28 Supervision strategies that closely monitor drug offenders in the community and provide specific, immediate consequences for compliance failures, such as Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation with Enforcement (HOPE) program, have also demonstrated success.29

Treatment strategies. Many states and localities are expanding drug treatment strategies to address heroin and other opioid abuse. In March 2015, Kentucky enacted a law that eliminates barriers to treatment in county jails and provides funding for evidence-based behavioral health or medication-assisted treatment for inmates with opiate addiction. It also allows local health departments to set up needle exchange sites, increases access to naloxone, and sends addicts who recover from overdoses into treatment rather than criminal prosecution.30 In Ohio, six county drug courts are participating in a state-funded pilot program that uses medication-assisted treatment for offenders with heroin and opioid addictions.31 In 2014, Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin (D) devoted his State of the State address to opiate addiction and has developed a model that pairs clinicians with treatment centers to provide coordinated care to residents addicted to opioids.32

Prevention strategies. A common strategy to prevent prescription painkiller abusers from becoming heroin users focuses on educating doctors and other prescribers about addiction risk factors. Providing prescribers with access to information about a patient’s history of drug addiction, tools to identify patients in need of drug treatment, and systemic support to collaborate with behavioral health professionals are central parts of a comprehensive plan to prevent opioid abuse and a subsequent transition to heroin use.33

Enhancement of criminal penalties

State and federal prisons held more than 300,000 drug offenders at the end of 2012.34 These offenders, in turn, were likely to serve more time behind bars than in the past. Drug offenders who left state prison in 2009 served an average of 2.2 years, an increase of 36 percent since 1990.35 Despite these statistics, research indicates that increasing criminal penalties for drug crimes has a limited ability to reduce demand.36

- Low deterrent value. Research shows that the chances of a typical drug dealer being caught during a transaction are about 1 in 15,000.37 With such low risk of detection, drug dealers on the street are unlikely to be deterred by the remote possibility of longer prison terms.

- Little impact on recidivism. Of the drug offenders who are convicted and sent to prison, approximately 75 percent return within three years of release.38 Studies show that for many offenders, serving longer sentences has little impact on recidivism and may even increase the likelihood of reoffending.39 Research has also found that many nonviolent drug offenders could be released up to two years sooner with no detriment to public safety.40

- Poor return on investment. An analysis in Washington state estimated that, in 2005, every taxpayer dollar spent incarcerating drug offenders returned just $0.35 in public safety and other benefits.41 This suggests that other states that have increased the use of incarceration or lengthened sentences for drug crimes may be receiving a similarly weak return on those investments.

Conclusion

Heroin abuse presents a growing challenge for policymakers at all levels of government. In 2013, federal authorities seized a record amount of heroin trafficked into the U.S., and the rate of domestic heroin use has tripled over the past decade, with lethal consequences: The number of annual heroin overdose deaths has increased 182 percent since 2008, 14 times the overdose rate for prescription drugs.

Policymakers are attempting to address the problem with a variety of approaches, such as expanding access to naloxone and encouraging good Samaritans to report heroin overdoses to authorities. Research indicates that deploying a combination of strategies—including targeted law enforcement and an improvement in the quality and availability of treatment—is most likely to reduce heroin abuse and its harmful effects.

Methodology notes

To gauge U.S. heroin use, abuse, and dependence, Pew relied on data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ National Survey of Drug Use and Health, an annual survey of approximately 70,000 Americans 12 and older. These figures should be viewed as conservative because some respondents may be unlikely to admit serious use of hard drugs and because many hard drug users are incarcerated or homeless and therefore unable to participate.

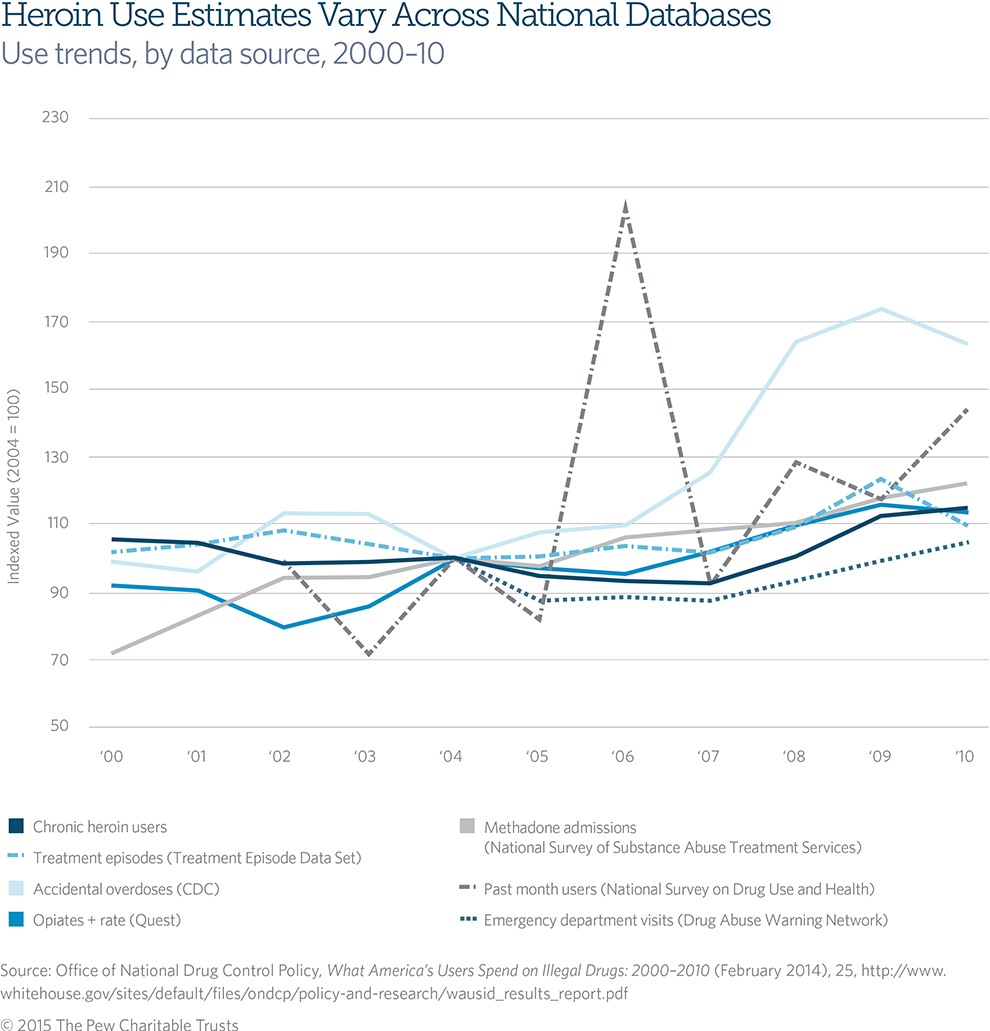

Researchers have tried to compensate for such underreporting by drawing information from other data sets, including treatment admissions, emergency room visits, overdoses, the Quest Diagnostics Drug Testing Index, and the Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program. The Rand Corp., for example, recently estimated the number of chronic heroin users by combining data from several of these sources. Figure 3 shows the variability in use estimates across data sources.42 The Rand researchers estimated that an accurate estimate of the number of daily or near-daily heroin users in 2010 was close to 1 million, more than 15 times the roughly 60,000 chronic users reported in the National Survey of Drug Use and Health the same year.43

Pew chose to rely on the survey, despite its likely underreporting, because it offers the most recent available information about domestic heroin use and includes data that are reliably and consistently collected.

Acknowledgments

The Pew Charitable Trusts’ public safety performance project would like to thank and acknowledge as an external reviewer the contribution of Eric L. Sevigny, Ph.D., associate professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina. Support for this brief was provided by Pew staff members Kathryn Zafft, John Gramlich, Craig Prins, Adam Gelb, and Darienne Gutierrez. We also thank Jennifer V. Doctors, Kristin Centrella, Bernard Ohanian, and Jennifer Peltak for editing, design, and Web support.

Endnotes

- Throughout this brief, the terms heroin “abuse,” “dependence,” and “addiction” are used interchangeably to describe compulsive drugseeking behavior that continues despite negative consequences. Heroin “use” refers to usage of the drug less than once a month or in a manner that does not characterize the same patterns as are evident in those who are addicted to the drug. More information can be found on the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s website on the science of drug abuse and addiction, http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/media-guide/science-drug-abuse-addiction-basics.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy, National Drug Control Strategy Data Supplement (2014), Table 71, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/ndcs_data_supplement_2014.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Drug Enforcement Administration, National Drug Threat Assessment Summary (2013), 5, http://www.dea.gov/resource-center/DIR-017-13%20NDTA%20Summary%20final.pdf; and Nick Miroff, “Tracing the U.S. Heroin Surge Back South of the Border as Mexican Cannabis Output Falls,” The Washington Post, April 6, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/tracing-the-usheroin-surge-back-south-of-the-border-as-mexican-cannabis-output-falls/2014/04/06/58dfc590-2123-4cc6-b664-1e5948960576_story.html.

- Miroff, “Tracing the U.S. Heroin Surge.”

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, RTI International, Results From the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables (2013), Tables 7.2A and 7.2B, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabsPDFWHTML2013/Web/HTML/NSDUH-DetTabsSect7peTabs1to45-2013.htm.

- Ibid., Table 7.40A.

- Ibid., Tables 1.1A and 5.14A. Percentage is calculated by dividing number of past-year heroin users who acknowledge dependence (Table 5.14A) by overall number of past-year users (Table 1.1A).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, CBHSQ Data Review: Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the United States (August 2013), abstract, http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/DR006/DR006/nonmedical-pain-reliever-use-2013.htm.

- Theodore J. Cicero, Matthew S. Ellis, and Hilary L. Surratt, “Effect of Abuse-Deterrent Formulation of OxyContin,” New England Journal of Medicine (July 12, 2012): 187–189, http://www.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/NEJMc1204141.

- Nora D. Volkow, “America’s Addiction to Opioids: Heroin and Prescription Drug Abuse,” testimony to Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control (May 14, 2014), http://www.drugabuse.gov/about-nida/legislative-activities/testimony-to-congress/2014/americasaddiction-to-opioids-heroin-prescription-drug-abuse.

- Christopher J. Mumola and Jennifer C. Karberg, Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisoners, 2004, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (October 2006), 2, http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudsfp04.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, RTI International, Results From the 2013 National Survey, Table 7.3B.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2013 Annual Report, Arrestee Drug Abuse Monitoring Program II (January 2014), http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/adam_ii_2013_annual_report.pdf.

- John Strang et al., “Drug Policy and the Public Good: Evidence for Effective Interventions,” The Lancet 379 (Jan. 7, 2012): 71–83.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Specific Drugs Involved in Drug Poisoning Deaths, 2008–2013, Table 40, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/heroin_deaths.pdf.

- Eric L. Sevigny and Michaela Saisana, Developing the U.S. Drug Consequences Indices, 2000–2009, Office of National Drug Control Policy (August 2013), 35, http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ developing_the_us_drug_consequences_indices_2000-2009_ august_2013.pdf.

- Robert Morrison, Colleen Haller, and Rick Harwood, “State Substance Abuse Agencies, Prescription Drugs, and Heroin Abuse: Results From a NASADAD Membership Inquiry,” National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors Inc. (2014), http://nasadad.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/NASADAD-Prescription-Drug-and-Heroin-Abuse-Inquiry-Full-Report-Final.pdf.

- Network for Public Health Law, Legal Interventions to Reduce Overdose Mortality: Naloxone Access and Overdose Good Samaritan Laws (November 2014), https://www.networkforphl.org/_asset/qz5pvn/network-naloxone-10-4.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Louisiana Regular Session, Act 368 (2014), http://www.legis.la.gov/legis/ViewDocument.aspx?d=912757&n=SB87%20Act%20368.

- Amber Widgery, National Conference of State Legislatures, e-mail to Pew, Sept. 12, 2014.

- U.S. Department of Justice, “Attorney General Holder Announces Plans for Federal Law Enforcement Personnel to Begin Carrying Naloxone” (July 31, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/attorney-general-holder-announces-plans-federal-law-enforcement-personnelbegin-carrying.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, “Law Enforcement Naloxone Toolkit,” https://www.bjatraining.org/tools/naloxone/Naloxone%2BBackground.

- Senator Rob Portman, “Portman, Whitehouse Introduce Bipartisan Legislation to Combat Drug Addiction and Support Recovering Addicts,” press release (Sept. 17, 2014), http://www.portman.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/press-releases?ID=c038a4e2-8bba-4821-a38c-dd1546165565.

- Police Executive Research Forum, “New Challenges for Police: A Heroin Epidemic and Changing Attitudes Toward Marijuana” (August 2014), http://www.policeforum.org/assets/docs/Critical_Issues_Series_2/a% 20heroin%20epidemic%20and%20changing%20 attitudes%20toward%20marijuana.pdf.

- Jonathan P. Caulkins and Peter Reuter, “Towards a Harm-Reduction Approach to Enforcement,” Safer Communities 8 (January 2009): 9–23, http://www.ukdpc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Article%20%20 Safer%20Communities%20Special%20 Issue_%20Law%20enforcement%20to%20reduce%20drug%20harms.pdf.

- Nicholas Corsaro et al., “The Impact of Drug Market Pulling Levers Policing on Neighborhood Violence,” Criminology & Public Policy 11, no. 2 (2012), http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2012.00798.x/pdf.

- Ojmarrh Mitchell et al., “Drug Courts’ Effects on Criminal Offending for Juveniles and Adults” (Feb. 2, 2012), http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/74.

- Angela Hawken and Mark Kleiman, Managing Drug Involved Probations With Swift and Certain Sanctions: Evaluating Hawaii’s HOPE (Dec. 2, 2009), National Institute of Justice, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/229023.pdf.

- Kentucky State Legislature, S.B. 192 (2015), https://legiscan.com/KY/drafts/SB192/2015.

- Mary Beth Lane, “Court Uses Vivitrol to Aid Addicts’ Recovery,” The Columbus Dispatch, April 20, 2015, http://www.dispatch.com/content/stories/local/2014/03/16/court-uses-vivitrol-to-aid-addicts-recovery.html.

- Governor Peter Shumlin, State of the State Address (Jan. 8, 2014), press release, http://governor.vermont.gov/newsroom-state-of-statespeech-2013; and Vermont Agency of Human Services, Department of Health and Department of Vermont Health Access, Care Alliance for Opioid Addiction, http://healthvermont.gov/adap/treatment/documents/CareAllianceOpioidAddiction.pdf.

- Researched Abuse, Diversion, and Addiction-Related Surveillance System, “RADARS® System Fifth Annual Scientific Meeting: Abuse Deterrent Formulations of Prescription Drugs” (April 28, 2011), http://www.thblack.com/links/rsd/RADARS%28R%29%20 System_2011%20Annual%20Meeting%20Summary.pdf.

- E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2013, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (September 2014), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p13.pdf.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, Time Served: The High Cost, Low Return on Prison Terms (June 2012), 3, http://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2012/06/06/time-served-the-high-cost-low-return-of-longer-prison-terms.

- Jonathan P. Caulkins, “The Need for Dynamic Drug Policy” (2006), http://repository.cmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=heinzworks; and Mark A.R. Kleiman, “Toward (More Nearly) Optimal Sentencing for Drug Offenders,” Criminology & Public Policy 3, no. 3 (July 2004), 435–440, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B6taQDF0rdAwYnJNTDU2bDVBNFU/edit.

- David Boyum and Peter Reuter, An Analytic Assessment of Drug Policy, American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research (2005), http://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/-an-analytic-assessment-of-us-drug-policy_112041831996.pdf.

- Matthew R. Durose, Alexia D. Cooper, and Howard N. Snyder, Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010, U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (April 2014), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rprts05p0510.pdf. 10

- Daniel S. Nagin, Francis T. Cullen, and Cheryl L. Jonson, “Imprisonment and Reoffending,” Crime and Justice 38, no. 1 (2009): 115–200, https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/abstract.aspx?ID=264336; Paul Gendreau et al., “The Effects of Community Sanctions and Incarceration on Recidivism,” Forum on Corrections Research 12, no. 2 (May 2000): 10–13, https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/Publications/ abstract.aspx?ID=185806; and Donald P. Green and Daniel Winik, “Using Random Judge Assignments to Estimate the Effects of Incarceration and Probation on Recidivism Among Drug Offenders,” Criminology 48, no. 2 (Oct. 28, 2009): 357–387, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1477673.

- The Pew Charitable Trusts, Time Served.

- Oregon Criminal Justice Commission, “Report to the Legislature” (January 2007), 11, http://library.state.or.us/repository/2013/201309271137355.

- Office of National Drug Control Policy, What America’s Users Spend on Illegal Drugs: 2000-2010 (February 2014), http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/wausid_results_report.pdf.

- Jonathan P. Caulkins et al., “Cocaine’s Fall and Marijuana’s Rise: Questions and Insights Based on New Estimates of Consumption and Expenditures in U.S. Drug Markets,” Addiction 110, no. 5 (July 14, 2014): 728–736, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25039446.