Restrictive Regulations Fuel New Mexico’s Housing Shortage

Available policy tools can help lower costs and unlock more availability

Median rents in New Mexico increased by 60% from October 2017 to October 2024, much more than the 27% recorded for the U.S. overall. The average price of a New Mexico home climbed even faster during that time, increasing by 70% and now topping $300,000.

Rising housing costs have helped to push up homelessness throughout the state. From 2017 to 2024, the number of people without homes increased by 87%, more than double the nation’s 40% rise. In Albuquerque, the number of unhoused people jumped by 108% over the same time period. Additionally, the share of chronically unhoused people in New Mexico increased from 33% in 2017 to 40% in 2024. Even relative to neighboring states that are also facing affordability challenges, such as Arizona (26% chronic unhoused) and Colorado (25%), New Mexico’s struggles stand out.

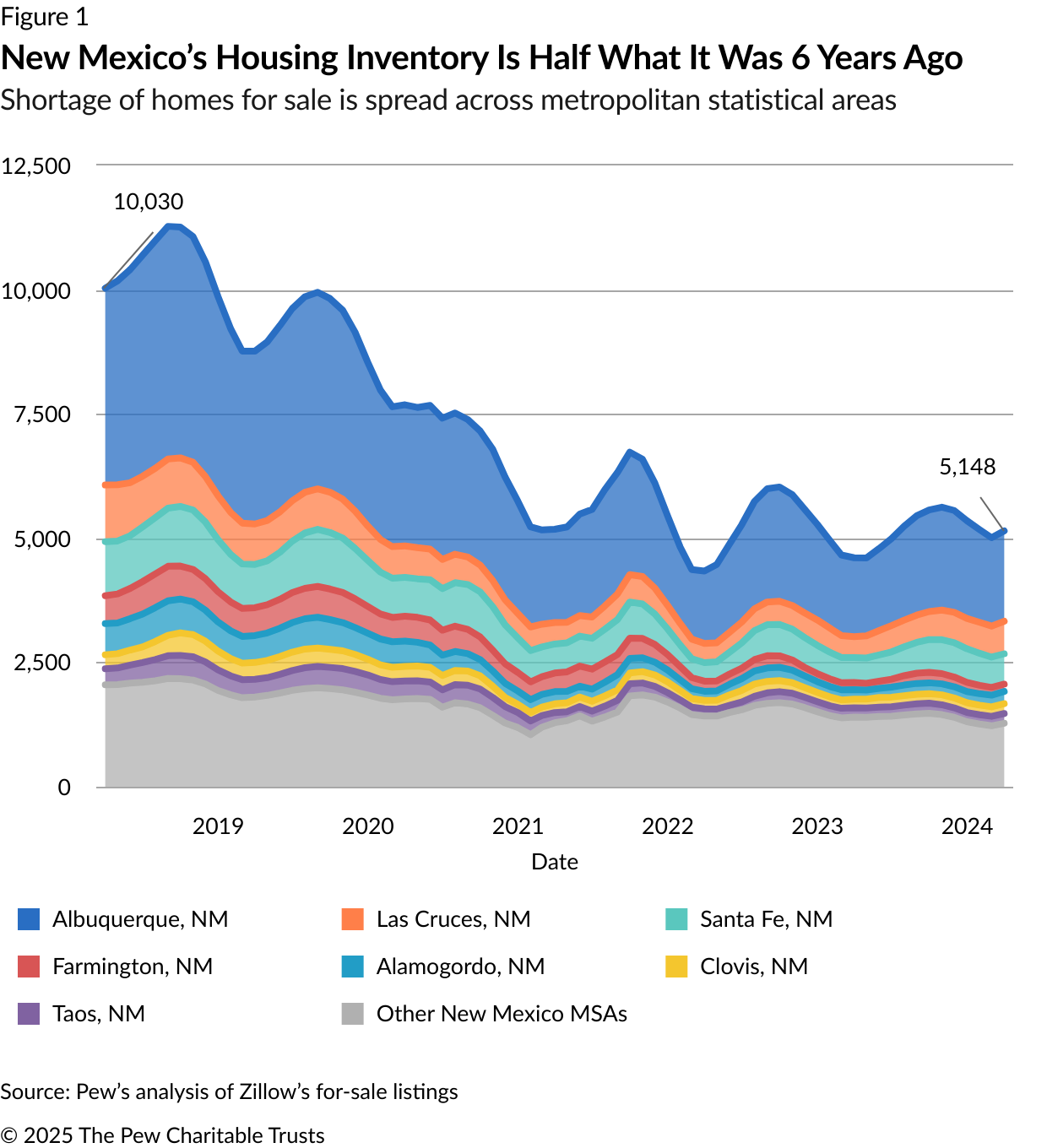

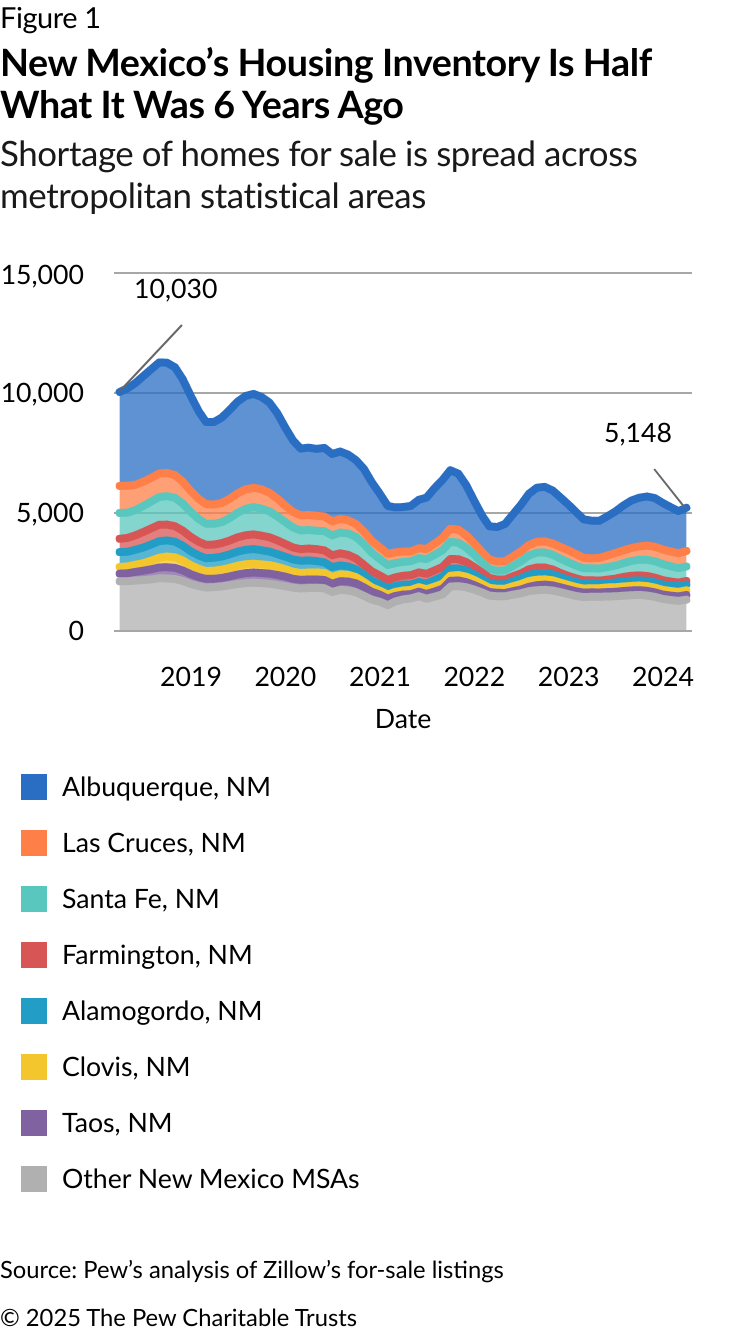

How can New Mexico policymakers at all levels slow the rise in housing costs? A drastic undersupply of housing has been a main cause of the affordability challenges. When supply is insufficient to meet residents’ needs, rental costs and home prices increase in response to the competition over a scarce resource. That scarcity has been growing in New Mexico. In March 2024, about half as many homes were available to buy as were available in March 2018 (Figure 1). With fewer homes for sale, average prices have climbed—up 78% in Albuquerque to $330,900. Prices in Santa Fe, meanwhile, have risen 68% since 2018 to nearly double the state level.

Many cities are afflicted by similar shortages. In many cases, strict land-use regulations have prevented new homes from being built. In cities and towns nationwide, such regulations have limited supply and caused rents and prices to rise.

New Mexico provides a prime example. In major cities such as Albuquerque, height restrictions and similar policies limit the kind of housing that can be built. Other Albuquerque policies, such as restrictive parking requirements, might not explicitly limit the amount of housing that can be built, but they still raise construction costs or require more land and essentially function as a cap on units. Although Albuquerque has added 31,400 jobs in the past three years, the city has permitted fewer than 9,000 units of housing over the same period.

In addition to the burden imposed by development standards, exclusionary zoning adds an additional hurdle to building more homes. The term refers to various explicit or implicit policies that effectively limit access to certain neighborhoods based on race, ethnicity, or income. These policies often work by banning or severely restricting multifamily or smaller-sized single-family homes.

Much residential land in New Mexico’s urban areas has long been reserved for single-unit detached homes; in Albuquerque, more than two-thirds of all parcels allow only single-family detached homes, the most expensive form of housing. Such housing often has additional land-use regulations, such as parking requirements, that further limit the amount of land available for housing. Currently, 79% of the housing inventory in Albuquerque and Santa Fe is this type.

Relaxing such exclusionary zoning to make it easier to build more townhomes or duplexes not only would reduce costs by increasing supply but also would respond to the housing needs of New Mexico’s population demographics. Given that 66% of state households contain either one or two people, New Mexico’s housing stock has far fewer starter homes, townhomes, and apartments than needed.

Although New Mexico policymakers amended the state’s building code in 2023 to increase maximum building heights, they have not taken the sorts of steps seen in other Western states—such as Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Montana, Oregon, Utah, and Washington—to allow more homes. All eight of those states have guaranteed most or all property owners the right to build an accessory dwelling unit (ADU)—a small home usually in a basement, backyard, or garage—on the same lot as a single-family home. Colorado allows apartments near all transit stops in metro areas. California, Hawaii, and Montana allow multifamily homes on all commercially zoned property, while Arizona does so on a portion of such property.

Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington also recently began allowing micro-units, where residents live in small private units but share some common areas such as kitchens and often bathrooms. The Pew Charitable Trusts has found that converting vacant commercial buildings into micro-units rather than conventional apartments can be more viable—and that micro-units are an especially effective strategy to create low-cost housing near jobs and commerce while reducing homelessness. Most of these Western states have enacted at least one type of reform to streamline permitting, an effective step to speed up housing construction.

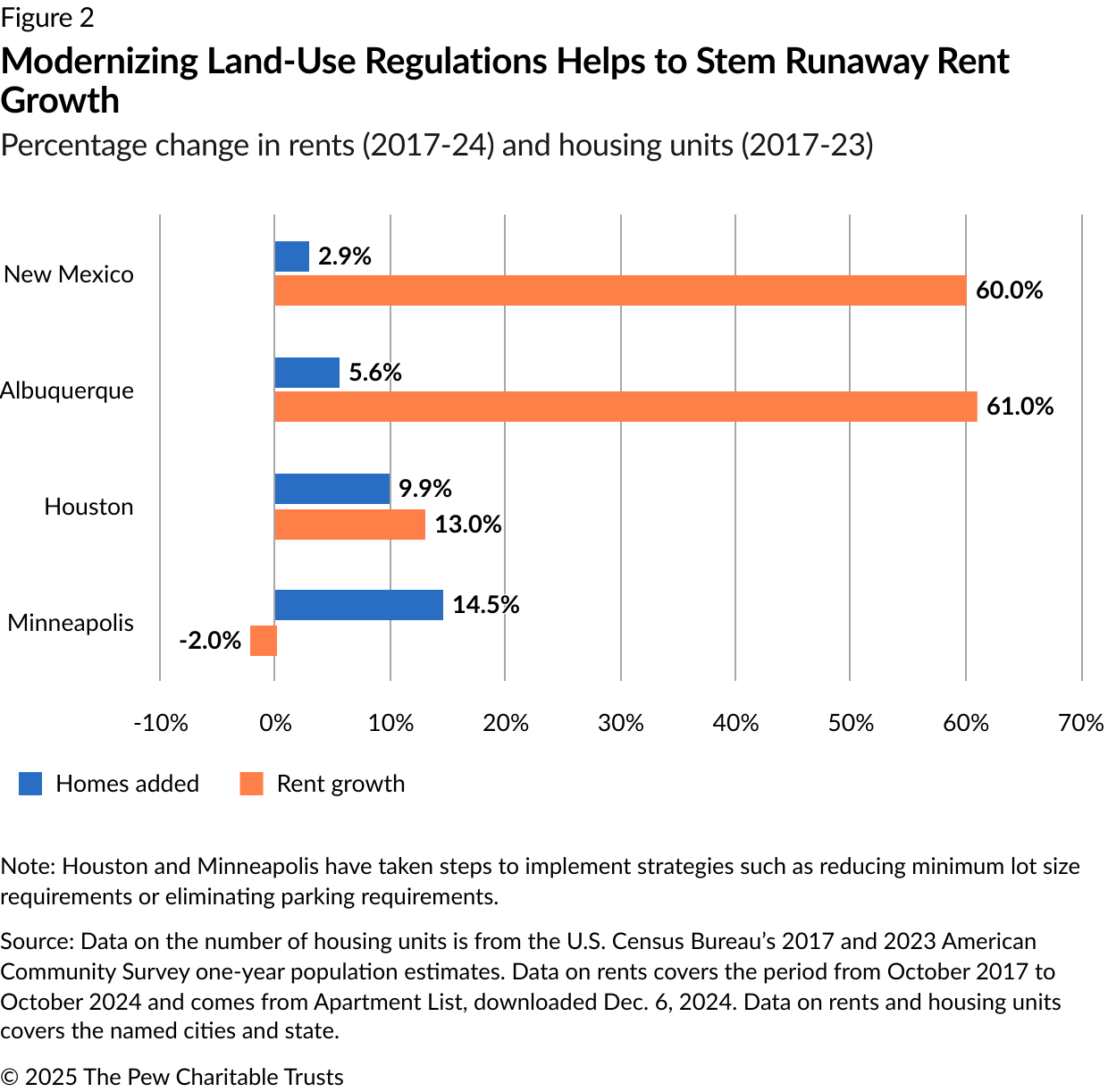

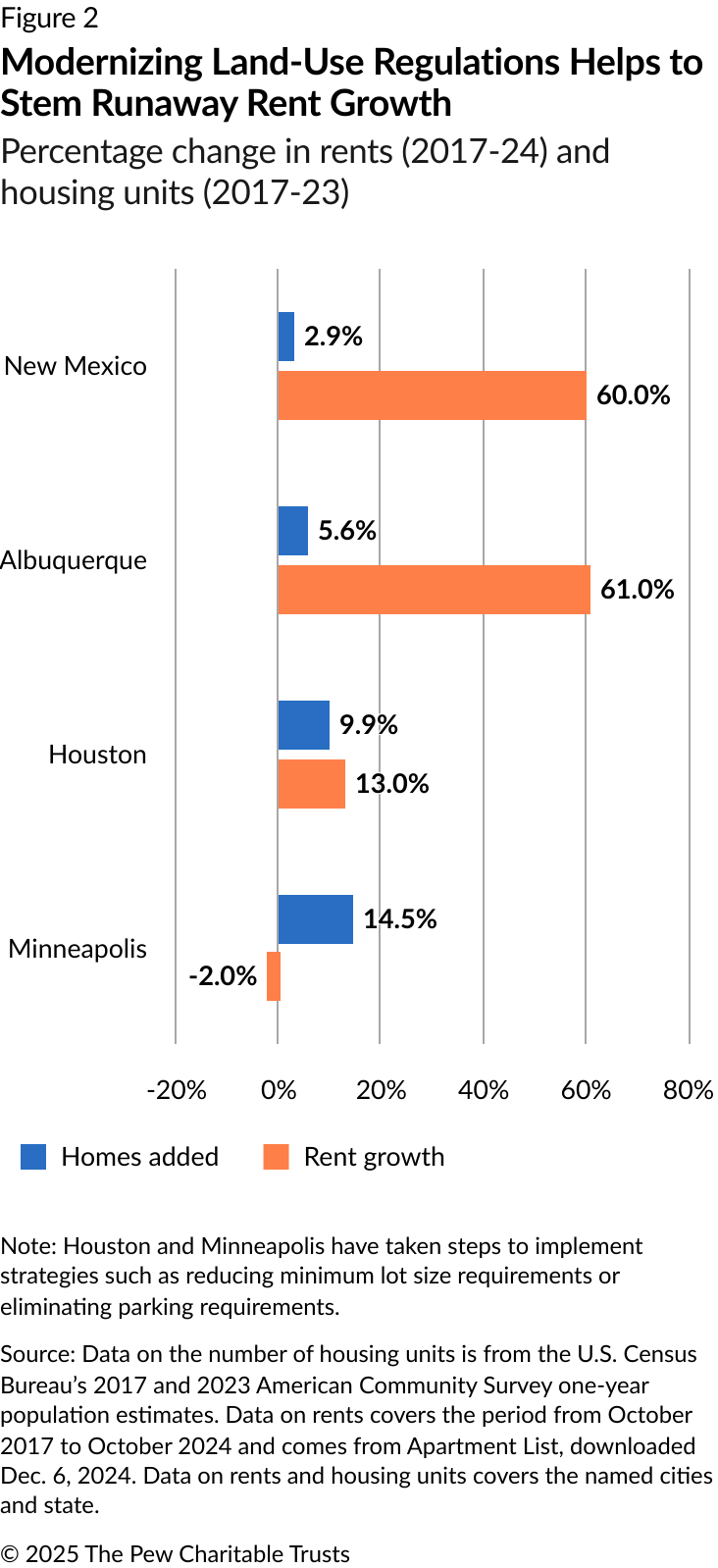

Some city actions elsewhere also provide valuable blueprints. Houston and Minneapolis, for example, have implemented ambitious strategies that have helped to improve affordability and are correlated with decreased homelessness. Houston reduced its minimum lot size requirement and created a town house boom—with 34,000 new units from 2007 to 2020 that were affordable for those around the local family median income. Minneapolis made building easier, in part by eliminating parking requirements, and allowing multifamily housing on all commercial and transit corridors. The city saw a sharp 14.5% increase in the number of homes added from 2017 to 2023, building at about six times the rate of New Mexico (Figure 2).

A 2023 Pew analysis found that zoning reforms such as these have improved affordability. Albuquerque and surrounding Bernalillo County have recently made it easier to build casitas, a type of ADU, to help increase housing supply. But this relatively small step falls short of the comprehensive reforms needed to stem Albuquerque’s huge rent spike.

Housing availability is critical to New Mexico’s Native American population, the fourth-largest in the United States. Of the 200,000 Native Americans across 23 tribes who call New Mexico home, concerning numbers face housing issues, especially overcrowding and low-quality housing that lacks plumbing and complete kitchens. Although overcrowding—having more than one person per room per household—applies only to 2% of U.S. households, a U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development report shows that 16% of Native American and Alaskan Native households live in overcrowded conditions.

Tribal areas and off-reservation counties that have high Native American populations with the most overcrowding are concentrated in the poorest regions nationwide, including areas of New Mexico and Arizona as well as the Plains states and Alaska. Although some Native Americans have cultural preferences for multigenerational living, a 2017 survey found that 80% of Native Americans in overcrowded homes would like to have more space to themselves. Additionally, research has linked overcrowding to increased stress, risk of infectious disease, and child development issues.

Zoning reform could address this issue in several ways, especially for Native Americans living off-reservation. According to research by the New Mexico Mortgage Finance Authority, the state’s high rates of overcrowding in specific regions, particularly in northwest counties such as McKinley and Cibola, can be partially attributed to a lack of affordable housing alternatives, though other factors—for example, cultural practices and family dynamics—could also play a role.

Policies that would directly increase the supply, such as allowing more apartments and townhomes or easing height or lot restrictions, would make it easier to build more and improve affordability. Land reform on tribal lands could also clarify zoning complexities and increase needed housing development.

Loosening zoning regulations could also benefit Native Americans facing homelessness. Although Native Americans made up 10% of New Mexico’s population in 2023, they accounted for 19% of the state’s homeless. Zoning reform could target one of the main drivers of displacement: high rents. When the supply of housing increases, the decreased competition for each home makes it harder for landlords to raise tenants’ rents.

Under current conditions of housing scarcity, Pew’s analysis of data from the real estate marketplace company Zillow finds that rents rose 62% from September 2017 to September 2024 in the lowest-income quarter of U.S. ZIP codes, compared with 44% in the highest-income quarter of ZIP codes. But in markets where a large supply of new apartments has helped to push down rents—including Phoenix, Salt Lake City, and Austin, Texas—rents have fallen the most for older, low-cost apartments. Added supply especially benefits lower-income residents.

Housing costs are usually the largest expense for families, and New Mexico’s housing shortage is raising those costs even higher. But reforms in other states show a path to success by allowing more and lower-cost housing to be built.

Alex Horowitz is a project director, Seva Rodnyansky is a manager, and Dennis Su is an associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.