Substance Use Disorder Increases Risk of Suicidal Thoughts and Attempts

Expanding screening, lowering barriers to behavioral health care can help prevent suicide

Overview

Each year, suicide and drug- and alcohol-related deaths account for more than 200,000 lives lost and hundreds of billions of dollars in medical, economic, and societal costs.1

Multiple studies show that, compared with the general population, people who use alcohol or drugs, or have substance use disorders (SUD), are at increased risk of dying by suicide.2 For example, the risk of death by suicide increases 5.8 times for people with alcohol use disorder (AUD), 8.1 times for people with alcohol and drug use disorders, and 11.2 times for people with alcohol, drug, and tobacco use disorders.3

It is important to examine how substance use and SUD affect not only suicide deaths but also suicidal thoughts and attempts. In 2022, for every death by suicide, about 32 people attempted suicide and more than 250 people seriously considered it.4 If health care providers, public health practitioners, and social scientists can better understand these patterns, they can more effectively screen people for suicide risk, substance use, and SUD; identify people at heightened risk; and connect them to care that can help save lives.

To shed light on these dynamics, Dr. Hillary Samples and The Pew Charitable Trusts conducted research, published as “National Trends and Disparities in Suicidal Ideation, Attempts, and Health Care Utilization Among U.S. Adults.”5 They found that substance use and SUD increase the odds that adults think seriously about and attempt suicide, which is consistent with studies that link SUD with increased risk of suicide deaths.

Key Definitions

- Substance use. Ingesting, inhaling, injecting, or absorbing alcohol, tobacco products, drugs, and other substances that can cause harmful effects.

- Substance use disorder. A medical condition characterized by clinically significant impairments in health, social function, and control over substance use.

- Suicidal ideation. A range of contemplations, wishes, and preoccupations with death and suicide, also called suicidal thoughts. Most instances do not progress to attempted suicide.

Rising rates and increased odds: The impact of substance use and SUDs on suicidal thoughts and behaviors

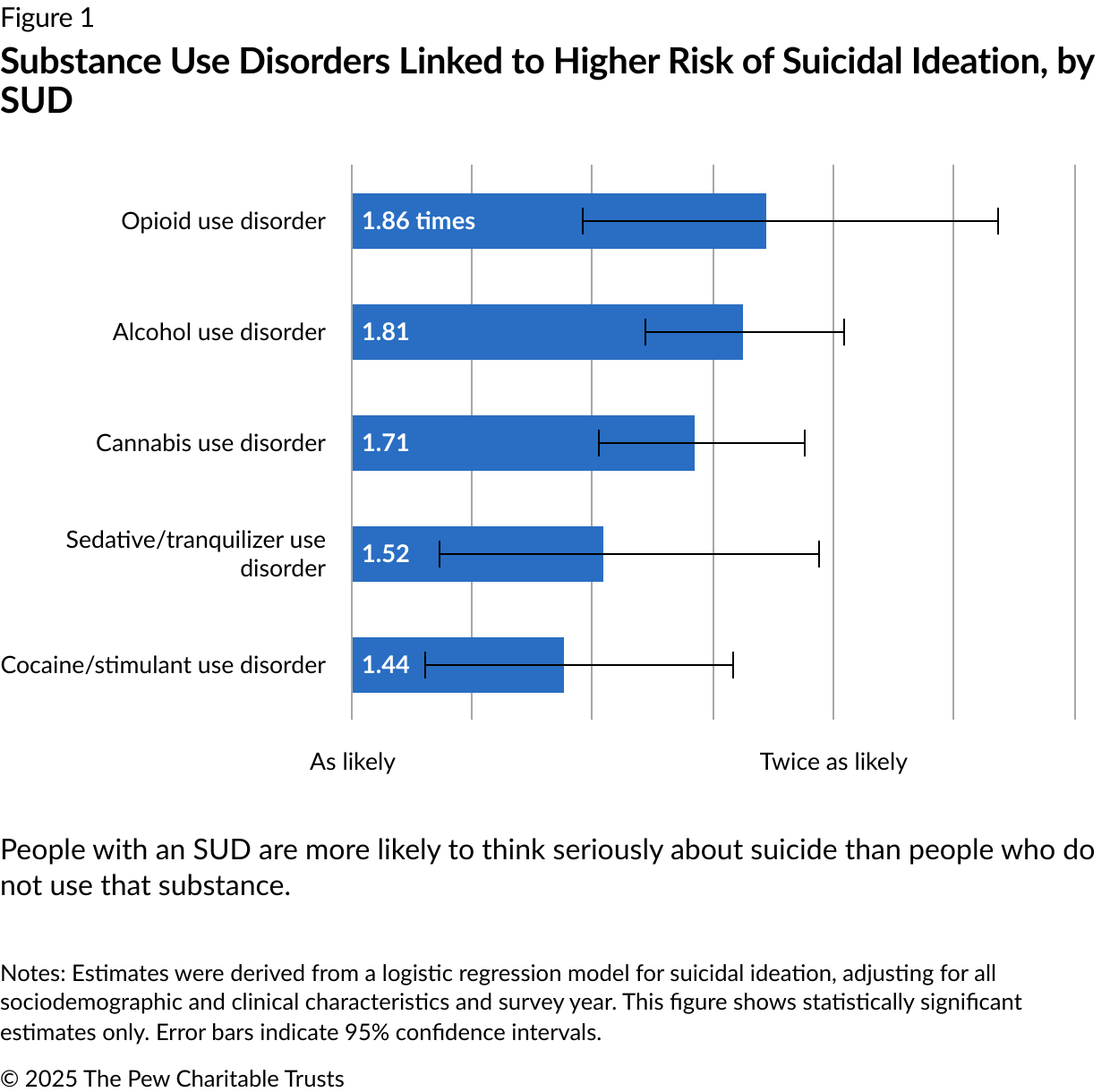

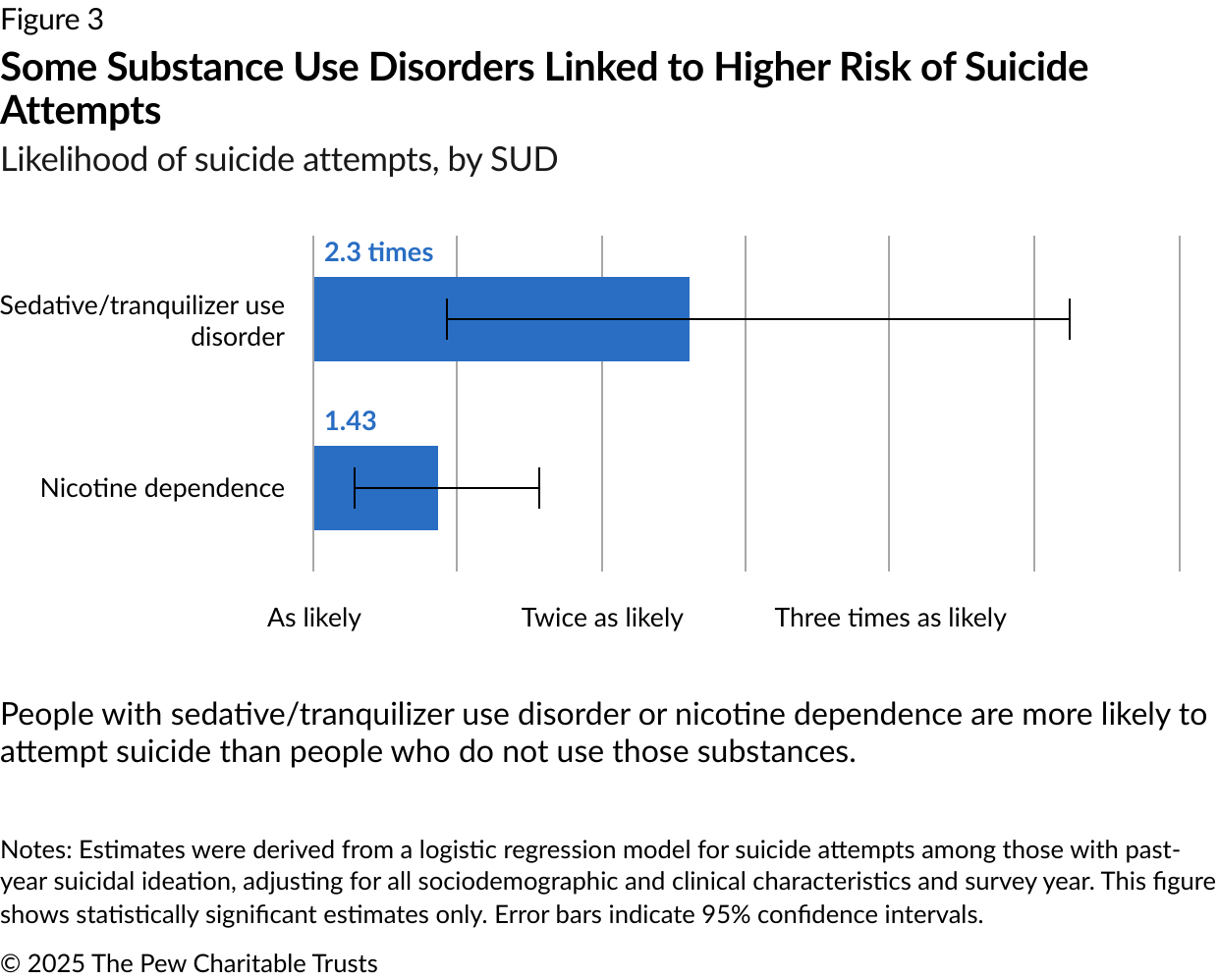

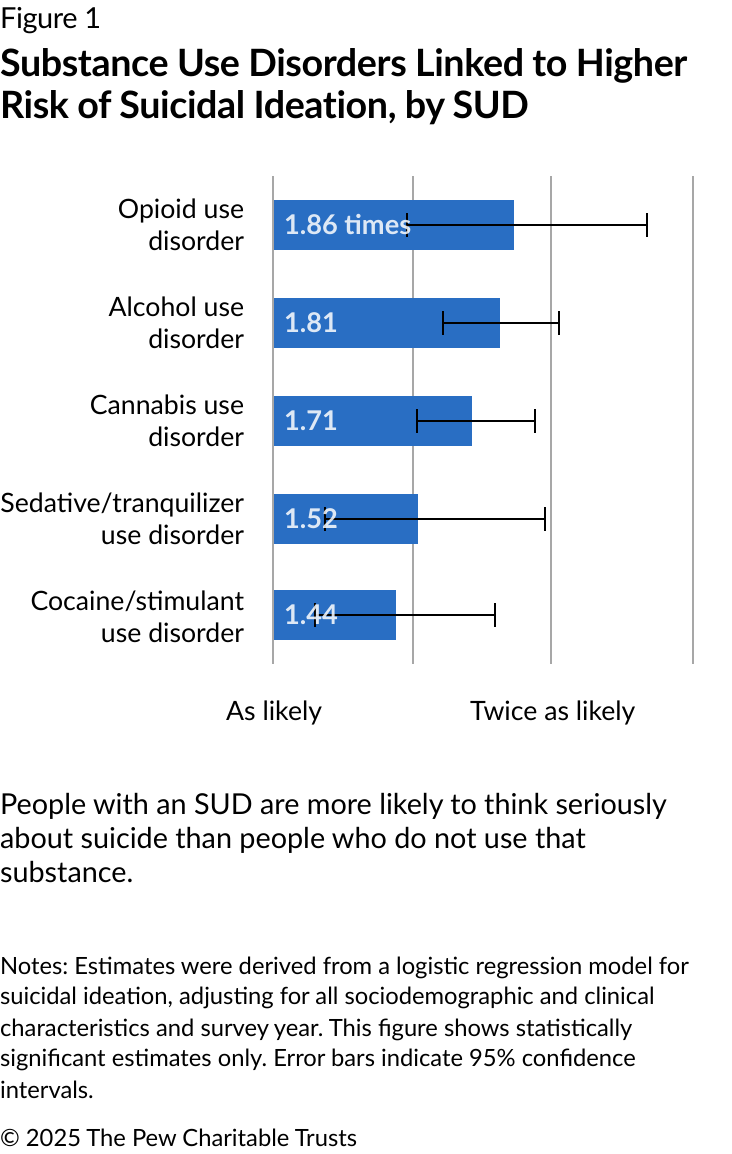

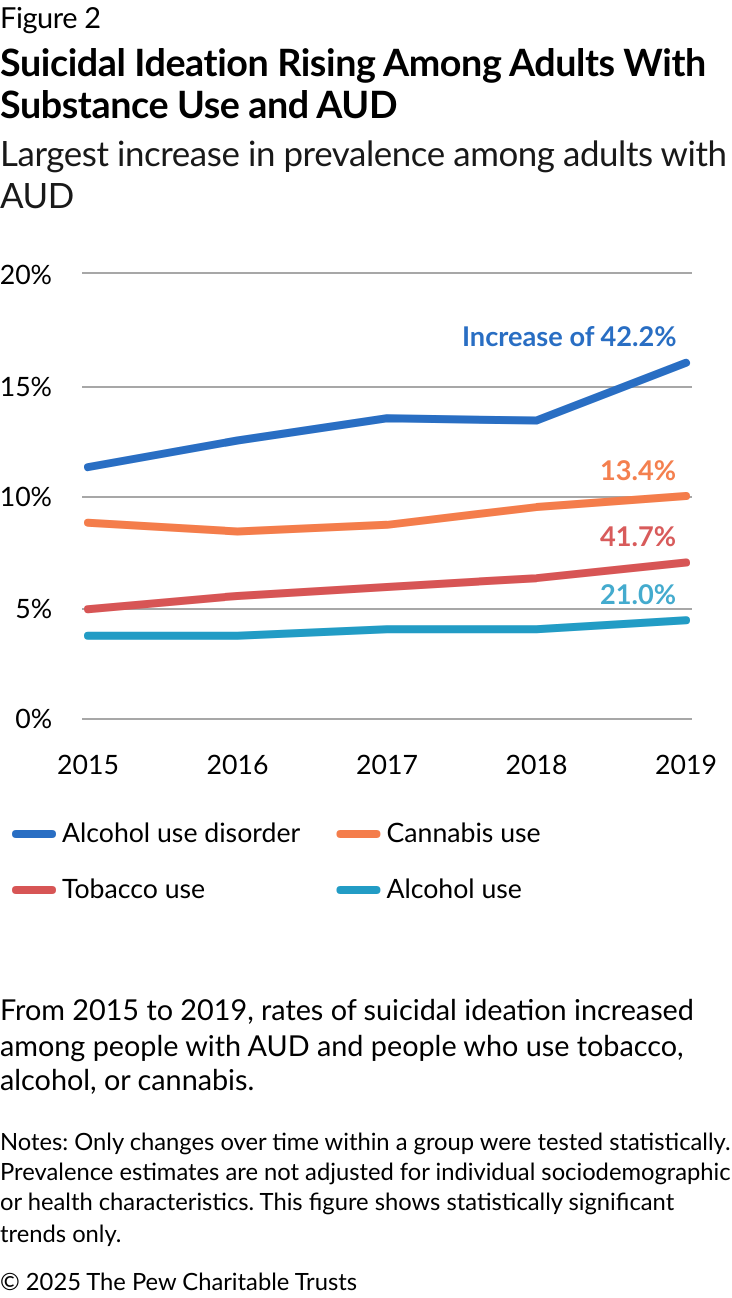

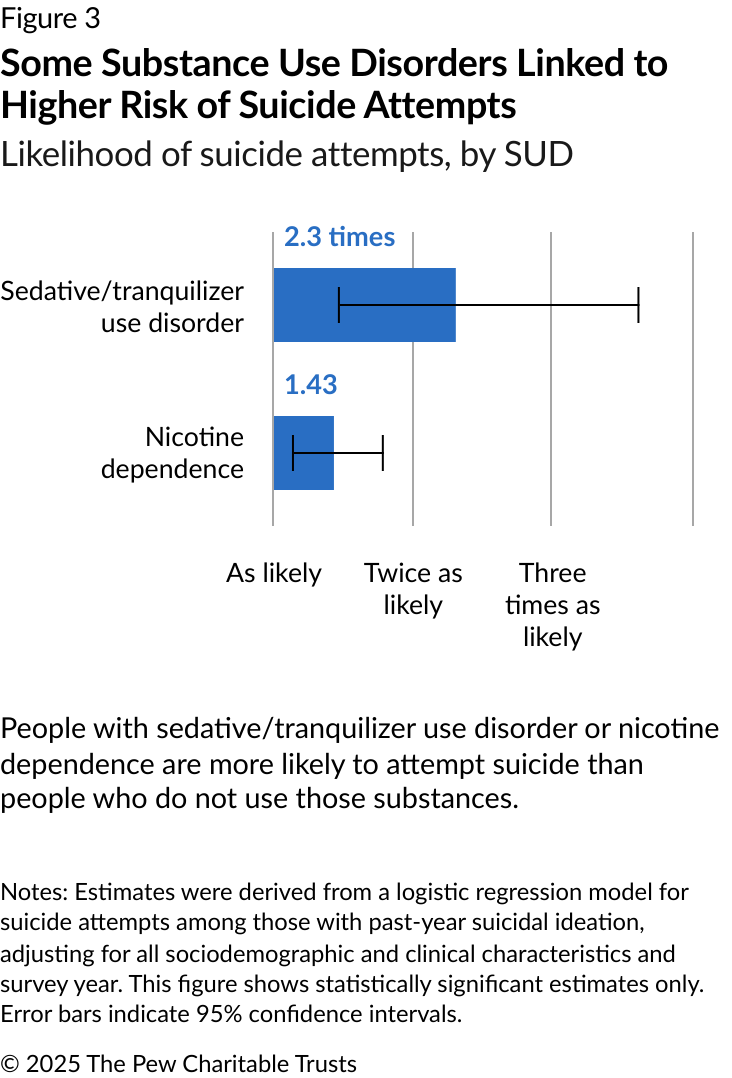

The following charts show that, from 2015 to 2019:

- Adults in the U.S. with alcohol, opioid, cocaine/stimulant, sedative/tranquilizer, or cannabis use disorders were more likely to think seriously about suicide than those without the disorders.

- The prevalence of suicidal ideation rose among adults with AUD and those who use alcohol, tobacco, or cannabis.

- Adults with sedative/tranquilizer use disorder or nicotine dependence were more likely to attempt suicide than those who do not use those substances.

The results are based on Dr. Samples’ analysis of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2015-19 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. The data and methodology were published in the journal Psychiatric Services, and an interactive overview of the data is available on Pew’s website.

The prevalence of suicide attempts from 2015 to 2019 did not increase or decrease significantly among people who thought seriously about suicide and reported any substance use or SUD.

Limited access to mental health care

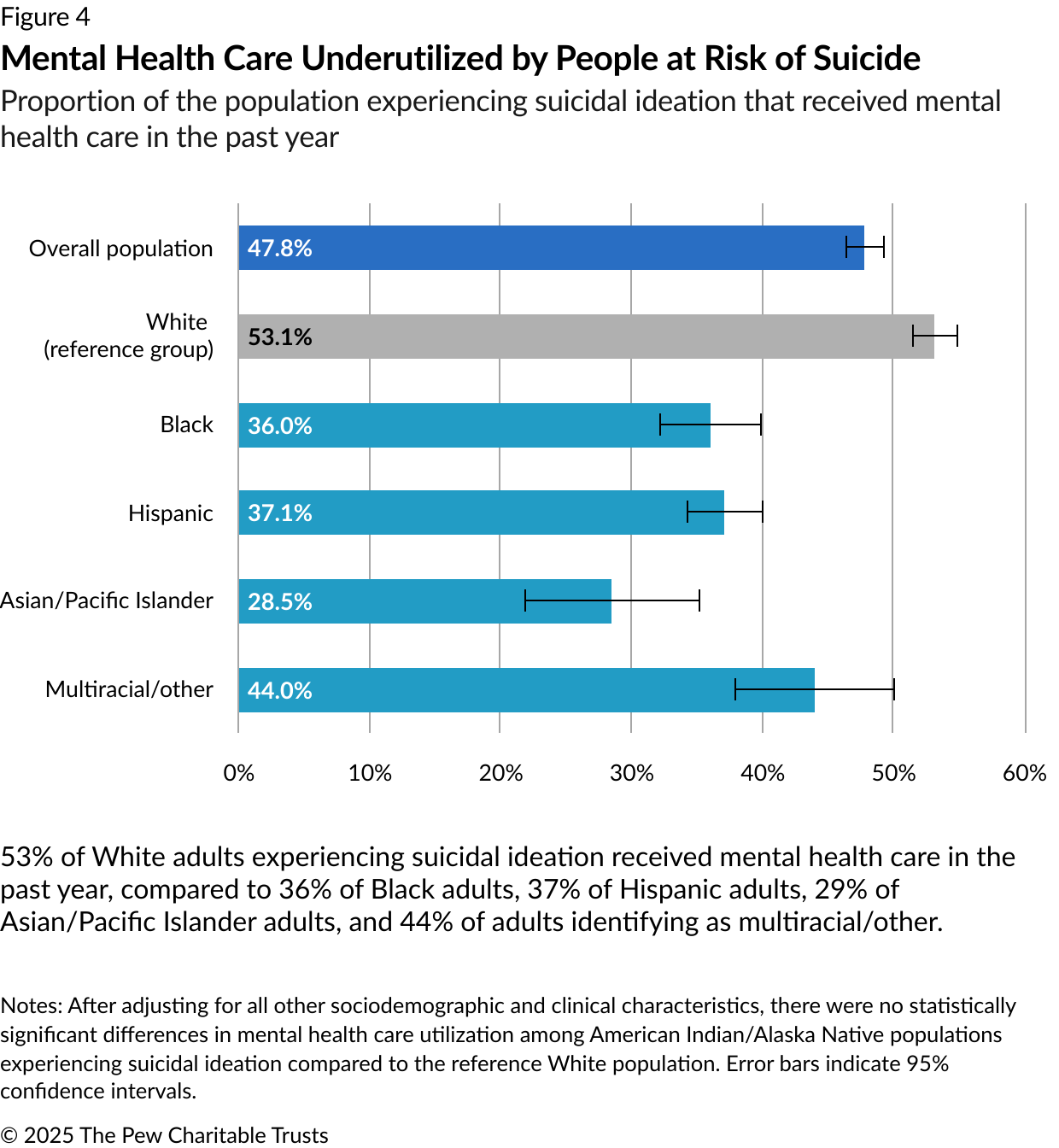

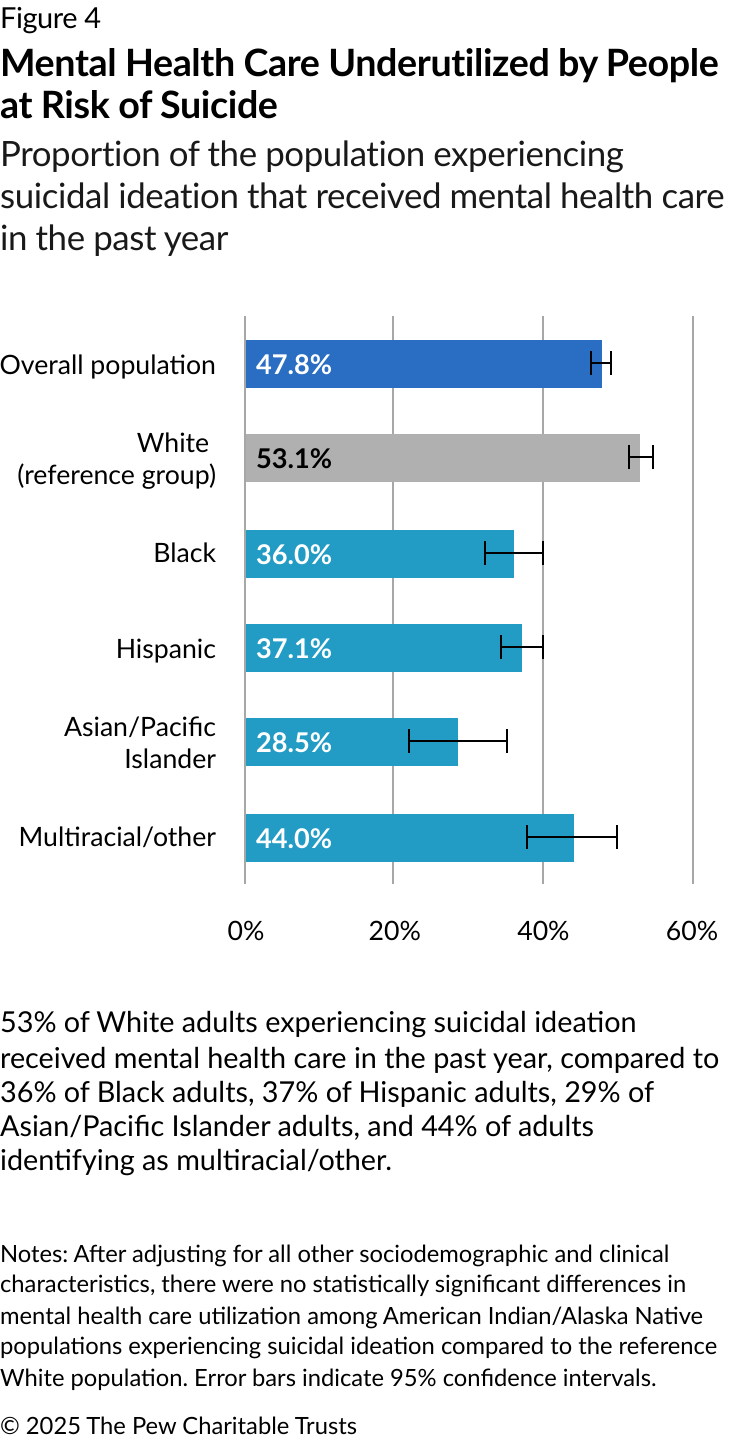

For people who thought seriously about suicide, 87% had received general health care within the past year, but only 48% received mental health care. Black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and multiracial adults accessed mental health care less often than White adults. Members of some racial and ethnic groups who thought seriously about suicide were less likely to receive mental health care than White adults, yet they were more likely or increasingly likely to attempt suicide.

Adults identifying as Black and Asian/Pacific Islander adults were 1.59 times and 1.93 times as likely as White adults, respectively, to attempt suicide. In addition, from 2015 to 2019, suicide attempts increased 48% among Black adults and 82% among adults identifying as multiracial/other, compared with a 33% decrease among White adults.

The suicide risk-substance use connection

The National Institute on Drug Abuse estimates that at least 5% of the 92,000 fatal drug overdoses in 2020 were intentional.6 There are many reasons people with SUDs are at increased risk of self-harm, including:

- Underlying health issues. People with depression, anxiety, or other mood disorders often develop SUDs, and vice versa.7 Together, these conditions increase the risk of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and mortality. In 2022, of 84.2 million adults in the U.S. with a SUD or mental illness, 21.5 million—or about 1 in 4—had both.8

- Stress, isolation, and bias. SUDs can cause serious physical and mental stress by damaging the brain, creating financial and legal problems, and straining personal relationships.9 Racism can also exacerbate harm by contributing directly to feelings that spur suicidal thoughts and behavior, and by driving health inequities that limit access to health insurance and care for people identifying as Black, Hispanic, American Indian/Alaska Native, and/or Asian American/Pacific Islander.10

- Impaired judgment. Drug and alcohol use impair judgment and impulse control, which can increase the risk of a suicide attempt or death, because people can act on suicidal impulse in minutes.11

- Access to lethal means. A person with access to prescription and illicit drugs as well as firearms—known as lethal means—is at greater risk of dying by suicide.12

Recommendations

Expand screening for suicide risk and substance use disorder. Health care providers can play an important role in screening for suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Research shows that about half of people who die by suicide see a health care professional in the month before their death.13

The Joint Commission, which accredits about 70% of U.S. hospitals, requires every accredited behavioral health facility to screen each patient for suicide risk.14 However, it requires general health care facilities to screen only when patients are seeking care primarily for behavioral health conditions. If someone is experiencing suicide risk and visits a hospital for physical health reasons, that person might not be screened for suicide risk.15

A 2017 study of eight hospital emergency departments found that universal screening—an evidence-based practice that includes screening of all patients for suicide risk regardless of the reason for their visit—followed by evidence-based interventions reduced total suicide attempts by 30%. According to a nationally representative survey of accredited nonpsychiatric hospitals conducted by Pew and The Joint Commission in 2023, 35% do not have a comprehensive universal suicide screening protocol. To improve identification of and care for people experiencing suicide risk, Pew advocates for universal screening in all U.S. hospitals.16

Health care providers can also improve their patients’ health and well-being by screening patients for SUDs and connecting them to necessary services. However, research indicates that such widespread screening does not happen and that even mental health specialists frequently underdiagnose SUD.17 All hospitals should make screening for SUDs a routine part of the care for all patients in both behavioral and general health care settings. Pew also supports the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force’s recommendation that primary care clinicians screen every adult for “unhealthy drug use” regardless of why they are seeking care.18

Increase access to care for substance use disorder and suicide risk. Medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and other interventions can be helpful for people experiencing behavioral health issues, but many people who need these treatments do not receive them. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration reported that, in 2022, nearly half of adults age 18 and older with any mental illness were not treated for it, and more than 85% of adults who needed SUD treatment did not get it.19

Stigma remains strongly associated with substance use and suicide, which impedes people from seeking care.20 Additionally, health care providers often do not receive specific training in suicide and SUD prevention and care, which hinders their ability to provide effective interventions and treatment.21 Primary care physicians, nurses, and other providers report that they are reluctant to screen for SUD and suicide risk and then refer patients to addiction treatment and other behavioral health services because they lack knowledge, training, support, or time.22 And federal and state policies limit when and where patients can receive medications for SUD, such as methadone, which is approved to treat opioid use disorder.23

During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal agencies temporarily expanded telehealth services for behavioral health. For example, doctors were allowed to prescribe buprenorphine, a medication for treating opioid use disorder, by phone or video—and this process proved to be very effective.24 And more people had greater access to suicide prevention and interventions.25

Telehealth accounted for a negligible proportion of behavioral health claims in January 2020 but grew to more than half of claims within a few months, and people continue to rely on it for behavioral health services more often than they did before the pandemic.26 In addition, although many state Medicaid programs pay for telehealth at the same rates as in-person care, it is not clear how many of these programs cover SUD-related services.27 Without assurances of sufficient reimbursement rates, providers may be unwilling or unable to offer telehealthbased treatment for people with SUDs.28

Although many states have made some of these telehealth-related policies permanent, the federal government has not.29

Policymakers can help more people receive lifesaving treatment by eliminating state-level restrictions on some medications for opioid use disorder, requiring health care providers to be trained in suicide prevention and SUD treatment and management, making federal telehealth flexibilities permanent, and setting Medicaid reimbursements for telehealth at the same levels as in-person care.

Provide safety counseling for people at risk for suicide. Once a provider screens a patient and assesses that the person is at risk for suicide, provider and patient can collaboratively develop a safety plan, which is a brief document written in the person’s own words with information that the person can use during a suicidal crisis.30 The plan should include any warning signs for that individual, as well as coping strategies, sources of support to contact, and steps to keep the environment safe by restricting access to lethal means, such as prescription and illicit drugs as well as firearms.

Tailor care to reflect different populations’ distinct health needs, cultures, and languages. Disparate rates of suicidal behavior, substance use disorder, and access to mental health care point to deep-seated inequities in society and the health system.31 Research is needed for better understanding of the disparities in risk factors and to inform the development of culturally responsive interventions that address populations’ unique needs and risk factors.32 Health care providers should then be trained to provide these evidence-based prevention and treatment services.

If you or someone you know needs help, please call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or visit 988lifeline.org and click on the chat button.

Endnotes

- National Center for Health Statistics, “U.S. Overdose Deaths Decrease in 2023, First Time Since 2018,” news release, May 15, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2024/20240515.htm. “Suicide Data and Statistics,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Oct. 29, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html. “A Look at the Latest Alcohol Death Data and Change Over the Last Decade,” Heather Saunders and Robin Rudowitz, KFF, May 23, 2024, https://www.kff.org/mental-health/issue-brief/a-look-at-the-latest-alcohol-death-data-and-change-over-the-last-decade/. “Drugs, Brains, and Behavior: The Science of Addiction,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2011, https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/introduction. Mengyao Li et al., “Medical Costs of Substance Use Disorders in the U.S. Employer-Sponsored Insurance Population,” JAMA Network Open 6, no. 1 (2023): e2252378-e78, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.52378. “How Illicit Drug Use Affects Business and the Economy,” Office of National Drug Control Policy, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/ondcp/ondcp-fact-sheets/how-illicit-drug-use-affects-business-and-the-economy. Erminia Fardone et al., “Economic Benefits of Substance Use Disorder Treatment: A Systematic Literature Review of Economic Evaluation Studies from 2003 to 2021,” Journal of Substance Use & Addiction Treatment 152 (2023): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.josat.2023.209084.

- Mina M. Rizk et al., “Suicide Risk and Addiction: The Impact of Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders,” Current Addiction Reports 8, no. 2 (2021): 194-207, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7955902/. Casey Crump et al., “Comparative Risk of Suicide by Specific Substance Use Disorders: A National Cohort Study,” Journal of Psychiatric Research 144 (2021): 247-54, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0022395621006166.

- Frances L. Lynch et al., “Substance Use Disorders and Risk of Suicide in a General U.S. Population: A Case Control Study,” Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 15, no. 1 (2020): 14, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-020-0181-1.

- “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results From the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt42731/2022-nsduh-nnr.pdf.

- Hillary Samples et al., “National Trends and Disparities in Suicidal Ideation, Attempts, and Health Care Utilization Among U.S. Adults,” Psychiatric Services (2024): https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ps.20230466.

- “Suicides by Drug Overdose Increased Among Young People, Elderly People, and Black Women, Despite Overall Downward Trend,” National Institutes of Health, news release, Feb. 2, 2022, https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/suicides-drug-overdose-increased-among-young-people-elderly-people-black-women-despite-overall-downward-tren.

- Thomas M. Kelly and Dennis C. Daley, “Integrated Treatment of Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders,” Social Work in Public Health 28 (2013): 388-406, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3753025/. Stephen Ross and Eric Peselow, “Co-Occurring Psychotic and Addictive Disorders: Neurobiology and Diagnosis,” Clinical Neuropharmacology 35, no. 5 (2012): 235-43, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22986797/.

- “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

- Mina M. Rizk et al., “Suicide Risk and Addiction: The Impact of Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorders.” Dennis C. Daley, “Family and Social Aspects of Substance Use Disorders and Treatment,” Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 21, no. 4 (2013): S73-s76, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4158844/. “Isolation and Addiction,” Addiction Center, https://www.addictioncenter.com/addiction/isolation/.

- S.M. Kogan et al., “Childhood Adversity and Racial Discrimination Forecast Suicidal and Death Ideation Among Emerging Adult Black Men: A Longitudinal Analysis,” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology (2024): https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fcdp0000641. D.W. Hollingsworth et al., “Experiencing Racial Microaggressions Influences Suicide Ideation Through Perceived Burdensomeness in African Americans,” Journal of Counseling Psychology 64, no. 1 (2017): 104-11, https://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fcou0000177. David R. Williams and Toni D. Rucker, “Understanding and Addressing Racial Disparities in Health Care,” Health Care Financing Review 21, no. 4 (2000): 75-90, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4194634/. Austin S. Kilaru et al., “Incidence of Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Following Nonfatal Overdose in Commercially Insured Patients,” JAMA Network Open 3, no. 5 (2020): e205852-e52, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5852. Latoya Hill, Samantha Artiga, and Anthony Damico, “Health Coverage by Race and Ethnicity, 2010-2022,” KFF, 2024, https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity/. Barbara Andraka-Christou, “Addressing Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder,” Health Affairs 40, no. 6 (2021): 920-27, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/abs/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02261. Janet R. Cummings et al., “Race/Ethnicity and Geographic Access to Medicaid Substance Use Disorder Treatment Facilities in the United States,” JAMA Psychiatry 71, no. 2 (2014): 190-96, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3575. Rit Shukla et al., “American Indian and Alaska Native Substance Use Treatment: Barriers and Facilitators According to an Implementation Framework,” Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment 155 (2023): 209095, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37277023/. Callie L. Wang et al., “Substance Use Disorders and Treatment in Asian American and Pacific Islander Women: A Scoping Review,” American Journal on Addictions 32, no. 3 (2023): 231-43, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36573305/.

- Michael Esang and Saeed Ahmed, “A Closer Look at Substance Use and Suicide,” American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal 13, no. 6 (2018): 6-8, https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/abs/10.1176/appi.ajp-rj.2018.130603. Eberhard A. Deisenhammer et al., “The Duration of the Suicidal Process: How Much Time Is Left for Intervention Between Consideration and Accomplishment of a Suicide Attempt?,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 70, no. 1 (2009): 19-24, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19026258/.

- “Brief Interventions That Can Make a Difference in Suicide Prevention,” American Academy of Pediatrics, https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/blueprint-for-youth-suicide-prevention/strategies-for-clinical-settings-for-youth-suicide-prevention/brief-interventions-that-can-make-a-difference-in-suicide-prevention/?srsltid=AfmBOorepPI5_DwB7G2-9vqWCPIPN5WmhPnmr4zuQOyuCK-uCaA2b64i. “With Gun Suicides at High, Safety Measures Should Be Discussed With At-Risk Patients,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/01/23/with-gun-suicides-at-high-safety-measures-should-be-discussed-with-at-risk-patients.

- Brian K. Ahmedani et al., “Health Care Contacts in the Year Before Suicide Death,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 29, no. 6 (2014): 870-77, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3.

- “Hospital Accreditation Fact Sheet,” The Joint Commission, https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/fact-sheets/facts-about-hospital-accreditation/.

- “FAQs: Ligature and/or Suicide Risk Reduction—Screening Requirements (HAP/CAH),” The Joint Commission, https://www.jointcommission.org/standards/standard-faqs/hospital-and-hospital-clinics/national-patient-safety-goals-npsg/000002240/.

- “Universal Screening Can Help Identify People at Risk for Suicide,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/01/25/universal-screening-can-help-identify-people-at-risk-for-suicide. Salome O. Chitavi et al., “Evaluating the Prevalence of Suicide Risk Screening Practices in Accredited Hospitals,” The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety (27 January 2025): https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2025.01.010. Link: https://www.jointcommissionjournal.com/article/S1553-7250(25)00040-6/fulltext

- Kevin A. Hallgren et al., “Prevalence of Documented Alcohol and Opioid Use Disorder Diagnoses and Treatments in a Regional Primary Care Practice-Based Research Network,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 110 (2020): 18-27, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31952624/. Pia M. Mauro et al., “Discussing Drug Use With Health Care Providers Is Associated With Perceived Need and Receipt of Drug Treatment Among Adults in the United States: We Need to Talk,” Medical Care 58, no. 7 (2020): 617-24, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32520836/. Tami L. Mark, Angélica Meinhofer, and Gary A. Zarkin, “Receipt of Substance Use Disorder Treatment Among Patients Visiting Psychiatrists,” Journal of Addiction Medicine 13, no. 3 (2019): 248-49, https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/fulltext/2019/06000/receipt_of_substance_use_disorder_treatment_among.16.aspx.

- “Unhealthy Drug Use: Screening,” U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, June 9, 2020, https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/drug-use-illicit-screening.

- “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.”

- “Stigma and Discrimination,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2022-06-01, https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/stigma-discrimination. “The Power of Lived Experience in Suicide Prevention,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/09/22/the-power-of-lived-experience-in-suicide-prevention.

- Janessa M. Graves et al., “Suicide Prevention Training: Policies for Health Care Professionals Across the United States as of October 2017,” American Journal of Public Health 108, no. 6 (2018): 760-68, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5944877/. “21 Million Americans Suffer from Addiction. Just 3,000 Physicians Are Specially Trained to Treat Them,” Susan Scutti, Association of American Medical Colleges, https://www.aamc.org/news/21-million-americans-suffer-addiction-just-3000-physicians-are-specially-trained-treat-them.

- Jennifer McNeely et al., “Barriers and Facilitators Affecting the Implementation of Substance Use Screening in Primary Care Clinics: A Qualitative Study of Patients, Providers, and Staff,” Addiction Science & Clinical Practice 13, no. 1 (2018): 8, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-018-0110-8. Melinda Campopiano von Klimo et al., “Physician Reluctance to Intervene in Addiction: A Systematic Review,” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 7 (2024): e2420837-e37, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.20837. Jared F. Roush et al., “Mental Health Professionals’ Suicide Risk Assessment and Management Practices,” The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 39, no. 1 (2018): https://econtent.hogrefe.com/doi/10.1027/0227-5910/a000478. Esther Adeniran et al., “A Scoping Review of Barriers and Facilitators to the Integration of Substance Use Treatment Services Into U.S. Mainstream Health Care,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence Reports 7 (2023): 100152, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772724623000227.

- Medications for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder, 42 C.F.R. Part 8, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2024, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/02/02/2024-01693/medications-for-the-treatment-of-opioid-use-disorder. “Overview of Opioid Treatment Program Regulations by State,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2022/09/overview-of-opioid-treatment-program-regulations-by-state.

- “Congress Should Permanently Extend Telehealth Flexibilities,” Marcelo H. Fernández-Viña and Sheri Doyle, The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/01/29/congress-should-permanently-extend-telehealth-flexibilities. “Telehealth Helps More Patients With Opioid Use Disorder Access Buprenorphine Treatment,” Marcelo H. Fernández-Viña, The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2023/04/06/telehealth-helps-more-patients-with-opioid-use-disorder-access-buprenorphine-treatment.

- “VA Telehealth Helps Veterans Get Suicide Prevention Treatment,” Treva Lutes, VA News, Oct. 8, 2023, https://news.va.gov/124530/va-telehealth-helps-veterans-suicide-prevention/.

- Norah Mulvaney-Day et al., “Trends in Use of Telehealth for Behavioral Health Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Payers and Employers,” American Journal of Health Promotion 36, no. 7 (2022): 1237-41, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9412131/. “Telehealth Demand: An Update Four Years After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Sanjula Jain, Trilliant Health, https://www.trillianthealth.com/market-research/studies/telehealth-demand-an-update-four-years-after-the-onset-of-the-covid-19-pandemic.

- “States Provide Payment Parity for Telehealth and in-Person Care,” National Academy for State Health Policy, Aug. 25, 2021, https://nashp.org/state-tracker/states-provide-payment-parity-for-telehealth-and-in-person-care/. “State Policy Changes Could Increase Access to Opioid Treatment Via Telehealth,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2021/12/state-policy-changes-could-increase-access-to-opioid-treatment-via-telehealth.

- Fernando A. Wilson et al., “An Examination of Private Payer Reimbursements to Primary Care Providers for Healthcare Services Using Telehealth, United States 2009-2013,” Center for Health Policy, 2016, https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/coph_policy_reports/27/.

- “State Telehealth Policy Trends: 2023 Year in Review,” American Medical Association, 2024, https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/ama-state-telehealth-policy-trends-2023.pdf. Jared Augenstein and Jacqueline Marks Smith, “Manatt Telehealth Policy Tracker: Tracking Ongoing Federal and State Telehealth Policy Changes,” Manatt, https://www.manatt.com/insights/white-papers/2024/manatt-telehealth-policy-tracker-tracking-ongoing.

- “Safety Planning Guide,” Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, https://sprc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/SafetyPlanningGuide-Quick-Guide-for-Clinicians.pdf.

- “Behavioral Health Needs Are Largely Unmet Across the U.S.,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, May 22, 2024, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2024/behavioral-health-needs-are-largely-unmet-across-the-us.

- “Black Adolescent Suicide Rate Reveals Urgent Need to Address Mental Health Care Barriers,” Farzana Akkas and Allison Corr, The Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2024/04/22/black-adolescent-suicide-rate-reveals-urgent-need-to-address-mental-health-care-barriers.