New Study Reveals True Size of Many U.S. Estuaries

Novel mapping could help government protect and restore habitats vital to wildlife, people, and economies

Many of the estuaries in the United States were once much larger than previously known, a critical finding as policymakers work to protect and restore these ecosystems. Estuaries—where a freshwater river or stream meets the ocean—provide nursery grounds and habitat for a huge range of birds, amphibians, mammals, and fish. These ecosystems also safeguard coastal communities from sea-level rise and offer opportunities for outdoor recreation, which can bolster local economies.

The finding on current and historical estuary size comes from a study, published in November in the journal Biological Conservation, exploring how 30 of the country’s estuaries have changed from as early as 1842 to today. The study determined that estuaries along the Pacific Coast have lost, on average, more than 60% of their tidal marshes since mapping began, while tidal marshes along the East Coast have decreased in size by 8% over that span. Conversely, some Gulf of Mexico estuaries have remained stable or grown over time—migrating landward into adjacent forests—while others in that region have barely shrunk at all.

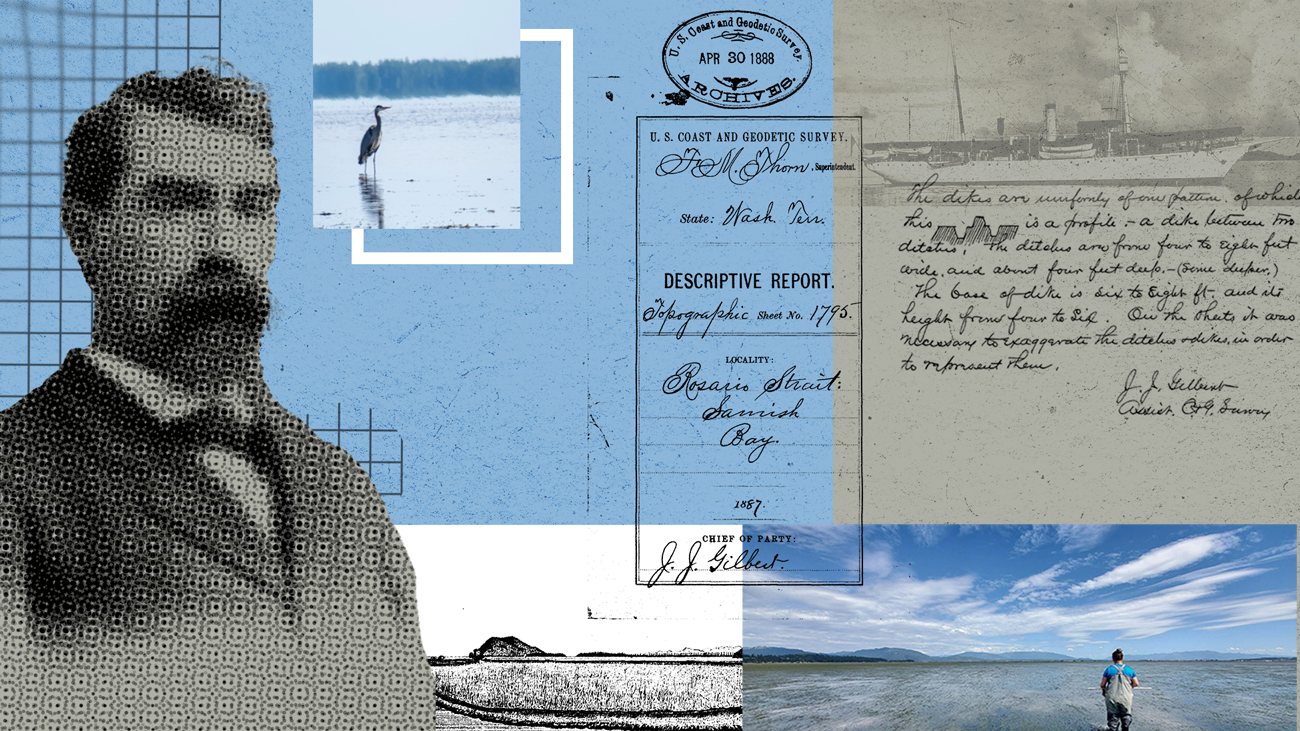

How An 1800s Mapping Pioneer Influenced a 2024 Estuary Study

More than 125 years after Captain John J. Gilbert meticulously mapped Washington state’s coast, his work is helping document profound changes in U.S. estuaries.

The National Estuarine Research Reserve System (NERRS) study incorporated maps created by cartographers such as Gilbert, who was 27 when he joined what came to be known as the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1864. Thomas Jefferson created the Survey—the country’s first civilian scientific agency—in 1806 to help sea captains avoid topographical hazards along the nation’s coasts.

In conducting their new study, NERRS experts pored over 28 of the Survey’s maps of areas that today are part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System. For example, some of Gilbert’s maps helped the study authors see how much of the present-day in Washington state’s Padilla Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve has been cut off from tidal flows. Gilbert spent at least 22 years of his nearly six decades with the Survey in Washington State.

Gilbert and other survey cartographers created an estimated 14,000 maps of U.S. coasts, inland waterways, and mountains. The first—of the Great South Bay shore on New York’s Long Island—dates to 1834.

“These maps give you a glimpse into the past, and it’s astounding how accurate and detailed some of them are,” said Andrea Woolfolk, stewardship coordinator of the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve in Monterey Bay, California, and one of the study’s two historical mapping experts.

The Survey set an ambitious goal of mapping the entire U.S. coastline, and these maps became the government’s and the maritime industry’s standard tool for understanding coastal environments at the time.

“Judging by his work, Gilbert was a masterful surveyor and cartographer,” Tom Schroeder, a former University of Washington professor who researched the Survey, wrote on his website.

“Notebooks in his lucid handwriting illustrate his qualities of thoughtful observation and decisive accuracy.” Schroeder, who stumbled across Gilbert’s maps at the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, D.C., while conducting an amateur study of San Juan County’s forests, is not connected to the NERRS study.

In his adventuresome career, Gilbert also took command of the steamship Pathfinder, which he piloted on surveys in Alaska and the Philippines in the early 1900s. In 1906, he returned to his native Virginia and rose to the post of inspector of hydrography and topography for the Survey.

Gilbert died in 1929 in Washington, D.C., at 84, eight years after retiring from the Survey, from a stomach ailment he contracted during his mapping travels. “Although some of the modern-day methods and instruments were lacking, he was able to produce substantially as accurate and thorough results as are possible today,” his obituary in The Evening Star of Washington, D.C., noted.

The Survey commissioned a ship named for Gilbert in 1930, which mapped the U.S. East Coast until 1962. The Survey was absorbed into the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in 1970, where its work continues today.

—T.W.

By understanding the true historical and potential size of estuaries, governments can make more informed decisions about conservation and restoration. The National Estuarine Research Reserve System led the study, which was funded by the National Estuarine Research Reserve System Science Collaborative.

The three-year study integrated historical and contemporary maps and data to chart how the estuaries that constitute the National Estuarine Research Reserve System have changed over time. The system is overseen by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management, which partners with state governments and other entities to designate and manage reserves throughout the U.S. and its territories. The system comprises 15 reserves on the East Coast; five on the West Coast; five along the Gulf of Mexico; one each in Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico; and two along the Great Lakes in areas that share many characteristics of estuarine ecosystems.

Healthy estuaries are economic, cultural, recreational, and environmental powerhouses around the globe. Up to 75% of the nation’s commercial fish catch spend some part of their lifespan in these habitats, which include seagrasses, mangroves, forests, and salt marshes. (Separately, The Pew Charitable Trusts is a co-founder of the South Atlantic Salt Marsh Initiative, which works to identify and address threats to salt marshes in the Southeast.) Estuaries face numerous threats, including climate change, encroaching development, and pollution and runoff.

“Our communities depend on the healthy natural infrastructure of estuaries to protect people and places,” Dr. Jeff Payne, director of NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management, wrote on an agency Web page summarizing the study. “Research like this provides the information managers need as they decide where to prioritize land and habitat protection.”

Innovative mapping reveals estuaries’ potential

The study’s authors combined tidal- and land-elevation data in a technique known as “elevation-based mapping,” a powerful way to visualize where estuaries are today and where they could be if artificial barriers to tides—such as dams, dikes, and other developments—were removed. The research team combined that data with historical analysis of topographic maps developed from 1842 to 1926, which helped identify estuarine habitats that had disappeared or were diminished because they were cut off from tidal flows.

For example, as early as 1886 in the estuary that would eventually become Padilla Bay Reserve in Washington state, extensive diking already was eroding habitats. The study determined that approximately half of the present-day reserve within the reach of tides has been cut off from natural tidal exchange, shrinking the estuary, making it less productive, and threatening its resilience.

This research determined that contemporary maps do not accurately reflect how far estuarine wetlands once extended, especially those that are forested. For example, nearly two-thirds of the tidal forests the study detected are not found in the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s National Wetlands Inventory—regarded as the country’s preeminent wetlands mapping resource.

“This is a critical finding: These East [Coast] and Gulf Coast estuaries are much more vast than what is mapped,” said Kerstin Wasson, research coordinator at California’s Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, and the study’s lead researcher. “We can’t protect estuaries if we don’t know where they are.”

The study’s researchers concluded that “comparing multiple, complementary mapping methods provides valuable new insights into past, current, and potential future estuary extent.”

Policymakers can use mapping to guide climate adaptation

The findings also highlight the need to tailor climate resilience strategies to regional conditions. For example, in places where diking, agriculture, and other commercial uses degraded wetlands, restoring tidal exchange could reestablish some lost habitats. In other locations where wetland habitats are moving landward, protecting and managing habitat migration corridors could restore these habitats and preserve their benefits.

“While more research is needed to understand the extent of wetland habitats, this mapping effort provides powerful insights for the coastal and Great Lakes communities who depend on these estuaries,” NOAA noted.

Tom Wheatley oversees The Pew Charitable Trusts’ work to increase resiliency for biodiversity and vulnerable communities in the Southeast and to support and expand the National Estuarine Research Reserve System as part of Pew’s U.S. conservation project.