Philadelphia's Evolving Immigrant Population Has Helped the City Grow

An influx of foreign-born residents has lifted the city, but will that trend endure?

Philadelphia’s immigrant population has been growing for three decades, while its U.S.-born population has declined in number since the 1950s. Those divergent, intertwined trends pose both big challenges and historic opportunities for local and regional leaders and residents.

Census data shows that, in the past two decades, immigrants were largely responsible for Philadelphia’s net growth in population following decades of deindustrialization and the movement of residents—including immigrants—mostly to suburban areas. From 2000 to 2022, the city’s foreign-born population rose by around 109,400, while its U.S.-born population dropped by about 59,700.

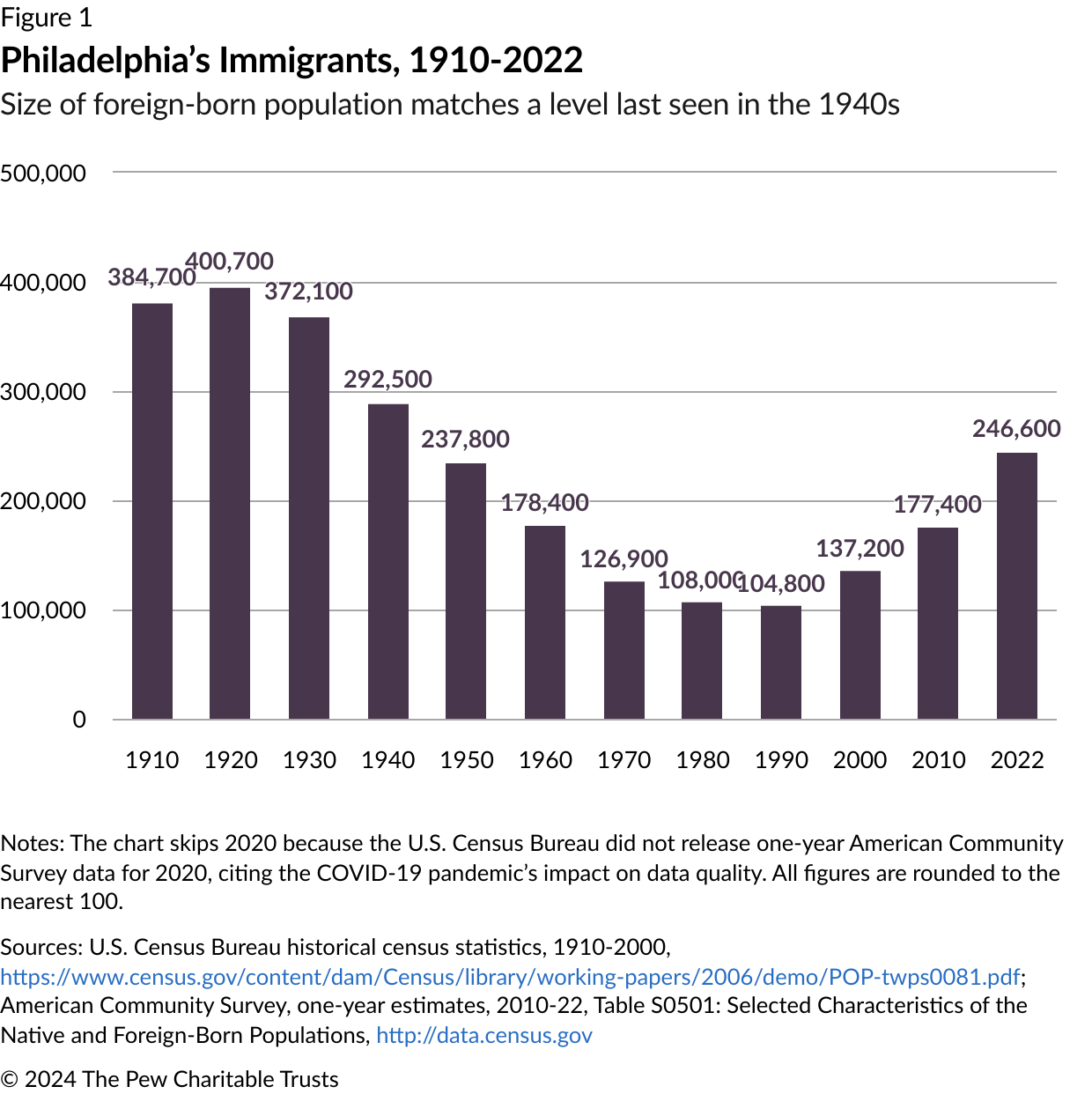

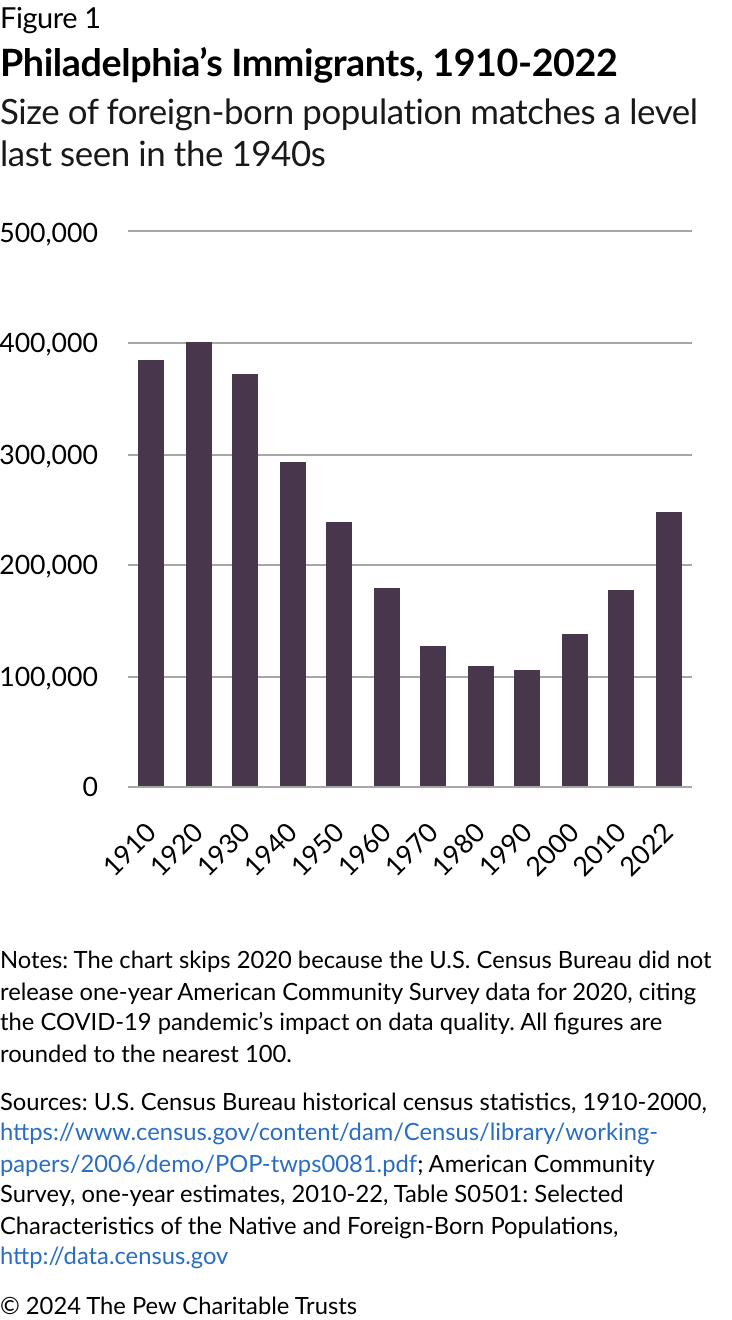

In the early 2000s, according to Brookings Institution research, the Philadelphia metro area transformed from a low-immigrant area to one of nine “re-emerging gateways,” with inflows resembling those of a century earlier. Though Philadelphia is still not a top U.S. destination for people born overseas, the city’s immigrant population has grown 80% since 2000, to around 246,600 in 2022, a level last reached in the 1940s. (See Figure 1.)

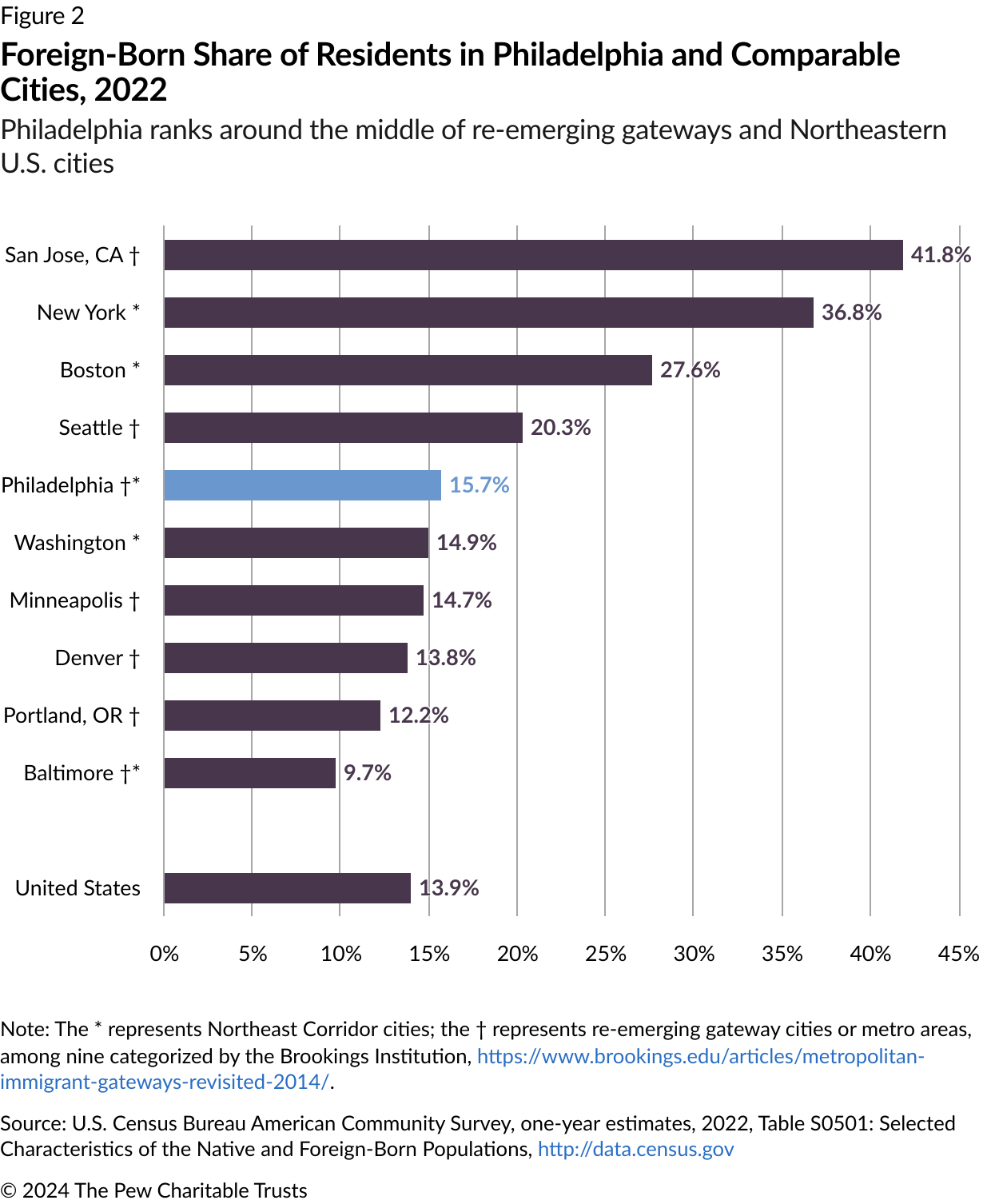

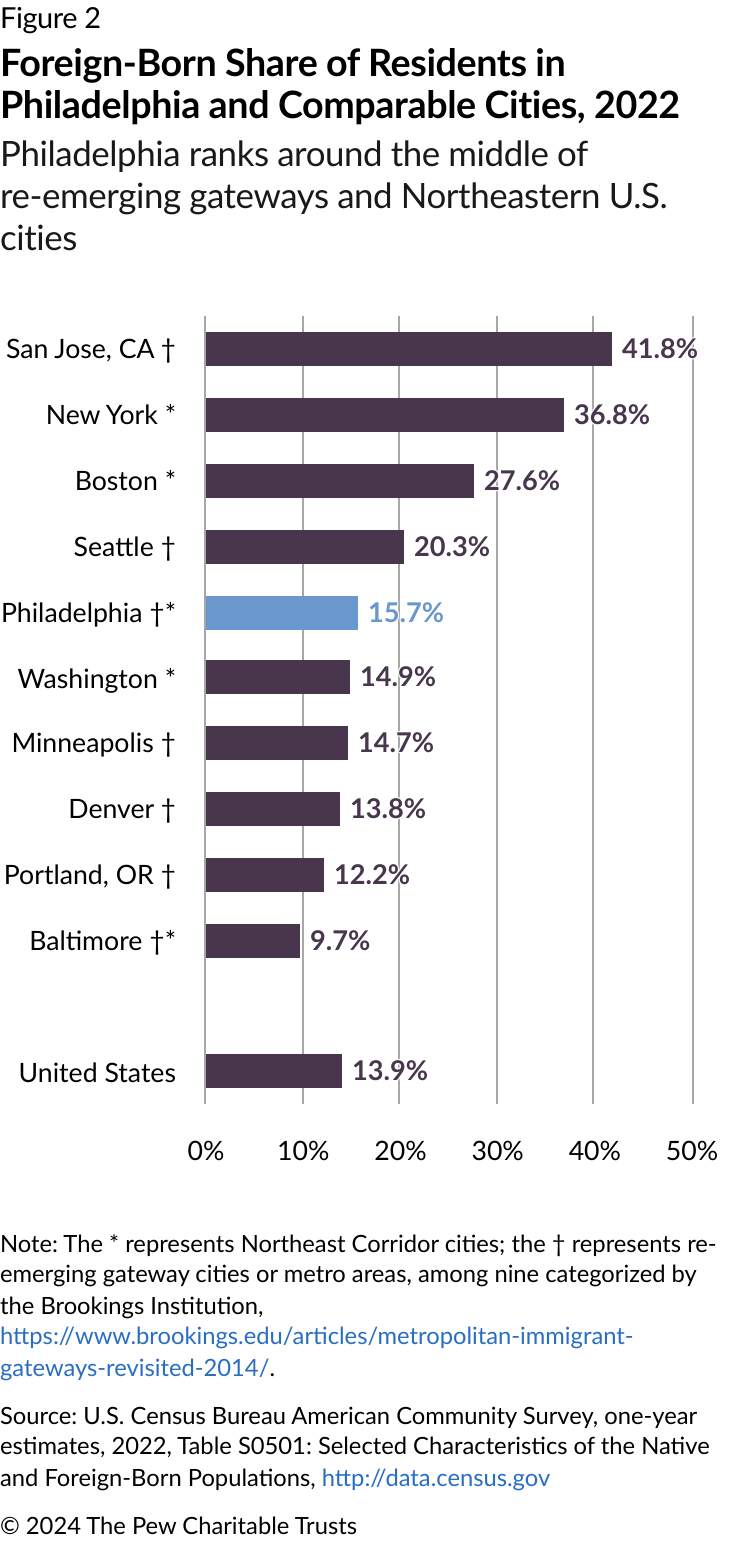

With the immigrant share of its population at 15.7% in 2022, Philadelphia was also back above the national average after three decades below it—and the city has risen relative to comparison cities used in this analysis, now around the midpoint among them. (See Figure 2.) That said, when accounting for each city’s total population, Philadelphia’s 15.7% share was still on the low side; the population-weighted average of seven re-emerging gateways was 19.5%; five Northeast Corridor cities, 30.9%; and all comparison cities combined, 29.1%.

In contrast, Philadelphia’s U.S.-born population has been shrinking for more than half a century. It peaked at 1.83 million in 1950 and has trended downward ever since, reaching 1.32 million in 2022, the lowest since 1910. The city’s overall growth from 2006 to 2020 was due mostly to immigrants and partly to U.S.-born Millennials. Its pandemic-related decline from 2020 to 2022 would have been steeper without immigrants, whose numbers had risen—but by less than before.

Given those demographic realities, a key question for the city may be whether foreign-born residents (also known as first-generation Americans) and the U.S.-born children of immigrants (second-generation Americans) will become a sustainable source of long-term growth for the population and the economy, as they were a century ago. Seminal research in 2017 under the auspices of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, using decades of demographic data, found that second-generation Americans have, on average, been the strongest contributors per capita to national and state economies and tax bases, compared with both previous and subsequent generations. On balance, their tax payments more than made up for the net cost in taxes for public services, especially public education, typically incurred by their immigrant parents. Research by Pew Research Center, the Cato Institute, and others has confirmed that first-generation Americans, on average, tend to struggle in low-income conditions their whole lives but set up second-generation Americans for enormous progress in socioeconomic terms, just as much today as in previous periods.

For Philadelphia, a return to population growth may hinge partly on whether the city keeps gaining immigrants and can hold onto U.S.-born children of immigrants, which is far from certain, given U.S.-born residents’ history of leaving the city. The picture so far is mixed: The second generation’s share of Philadelphia’s population over the past two decades has held steady, around 10% to 12%, although more second-generation Americans were teens and young adults during that period than in the past, according to Pew’s analysis of federal Current Population Survey data. The combined first- and second-generation share was around 28% in 2018-22, a period when immigration was curtailed by federal restrictions and the COVID-19 pandemic.

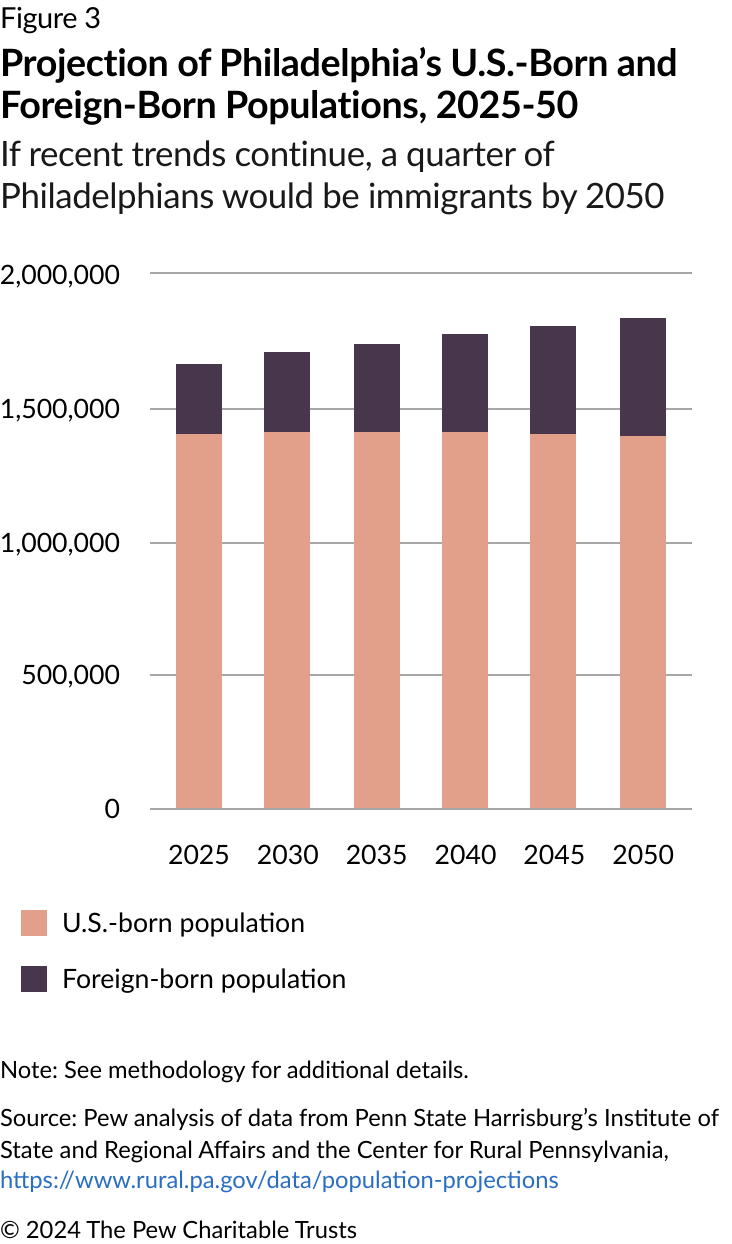

Immigrants themselves are a different story. If pre-pandemic trends continue, they could help lift the city’s population over 1,836,000 by 2050, based on Pew’s analysis of projections by Penn State Harrisburg’s Institute of State and Regional Affairs and the Center for Rural Pennsylvania. The U.S.-born population is projected to be essentially flat during this period. (See Figure 3.) Importantly, these projections do not include scenarios in which immigration drops—as it did from 2017 to 2020—or accelerates. The Penn State projections align with projections for the nation produced by the Congressional Budget Office and the U.S. Census Bureau.

Thomas Ginsberg is a senior officer and Maridarlyn Gonzalez is a senior associate with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ Philadelphia research and policy initiative.