Public Workers Preparing for Retirement

Top findings from a survey of Michigan’s state employees

Overview

State and local pension systems have adopted significant reforms in recent years in an effort to become fiscally sustainable. Today, policymakers across the country are considering additional changes to public retirement benefits as they work both to meet their commitments and help ensure the financial futures of their workers. The impact of these reforms on recruitment and retention of a talented workforce remains unclear, and the need to understand workers’ thoughts and attitudes about retirement benefits is growing.

In order to meet this need, The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Michigan Office of Retirement Services commissioned a survey of Michigan state workers (“Michigan survey”) in early 2015. SSRS, a national independent research company, conducted the survey to gain insight into how public employees enrolled in the state’s defined contribution plan (“Michigan state workers”) value their benefits, to gauge their expectations about retirement, and to see how well these benefits meet workers’ needs. Michigan has a long-established mandatory defined contribution retirement program for state employees, providing an excellent opportunity to examine public workers’ views on retirement benefits. A number of other states provide a mandatory or optional defined contribution plan for state workers, and most provide a mandatory or optional defined contribution plan plan for university employees.

Survey respondents included state employees who are health care and social work professionals, highly skilled workers such as engineers and lawyers, clerical workers, and skilled trade workers. Municipal workers and teachers were not part of the sample because they belong to separate retirement systems.

Michigan, along with Alaska and Oklahoma, has switched from a defined benefit pension plan to a mandatory defined contribution retirement plan for new state employees. Since 1997, all new eligible Michigan state employees have been enrolled automatically in the defined contribution plan. At the start of 2015, 32,575 state workers were enrolled in the plan.

In addition to providing the findings from the survey, this brief compares the results to Pew’s nationwide survey of state and local government workers (“national state and local workers”), conducted in collaboration with the Center for State and Local Government Excellence (“national survey”) in late 2013.

Key findings

The Michigan survey suggests seemingly conflicting attitudes about retirement, with many state workers expressing some unease about the future but also saying they plan to retire earlier than many other workers. Among the key findings:

- About three-quarters of Michigan state workers contribute enough to their account to receive the full employer match, and most of these workers said they cannot afford to contribute any money in addition to that amount.

- Michigan state workers generally report lower confidence than state and local government workers in other states that they will be able to receive their full Social Security benefits, and that they will have the resources to live comfortably in retirement. In addition, nearly all say they would like access to guaranteed income in retirement.

- Despite doubts over their future well-being, Michigan state workers generally expect to retire earlier than the average U.S. worker, and most said they are satisfied with their salary and retirement benefits.1

- Michigan state workers’ views on retirement and compensation differ by age. Younger workers generally see retirement planning as a lower priority and express a greater preference for higher salary, instead of more generous retirement benefits, than do those 30 and older.

How the Michigan plan works

Newly eligible Michigan state workers are automatically enrolled in the state’s pretax account, starting with a 3 percent default employee contribution. The state adds to that by providing a default contribution of 4 percent of salary and also matches the employee’s contribution dollar for dollar up to 3 percent. Together, this amounts to a total default contribution of 10 percent of salary: 3 percent from the employee and 7 percent from the state.2 Employees then may add to their contributions, up to the limits set by the Internal Revenue Service.3

Also by default, the contributions are invested in target date funds managed by State Street Global Advisors, with investments based on birth date and an anticipated retirement age of 65.

These Michigan workers are immediately vested in their own contributions and any earnings on those investments. After two years of service, they are 50 percent vested in the state’s contributions. That share rises to 75 percent after three years and 100 percent after four.

Participants over age 591/2 who are still actively employed by the state may begin withdrawing from their accounts without penalty. Upon retirement, Michigan state workers in the plan can choose among multiple payout options, including lump sum, installments (e.g., monthly, quarterly, or annually), or a combination of regular installments and a lump sum. The state provides employees who want to purchase an annuity with information on how to transfer their balances to an approved annuity provider. In addition to the defined contribution plan, Michigan state workers also participate in and contribute to Social Security.

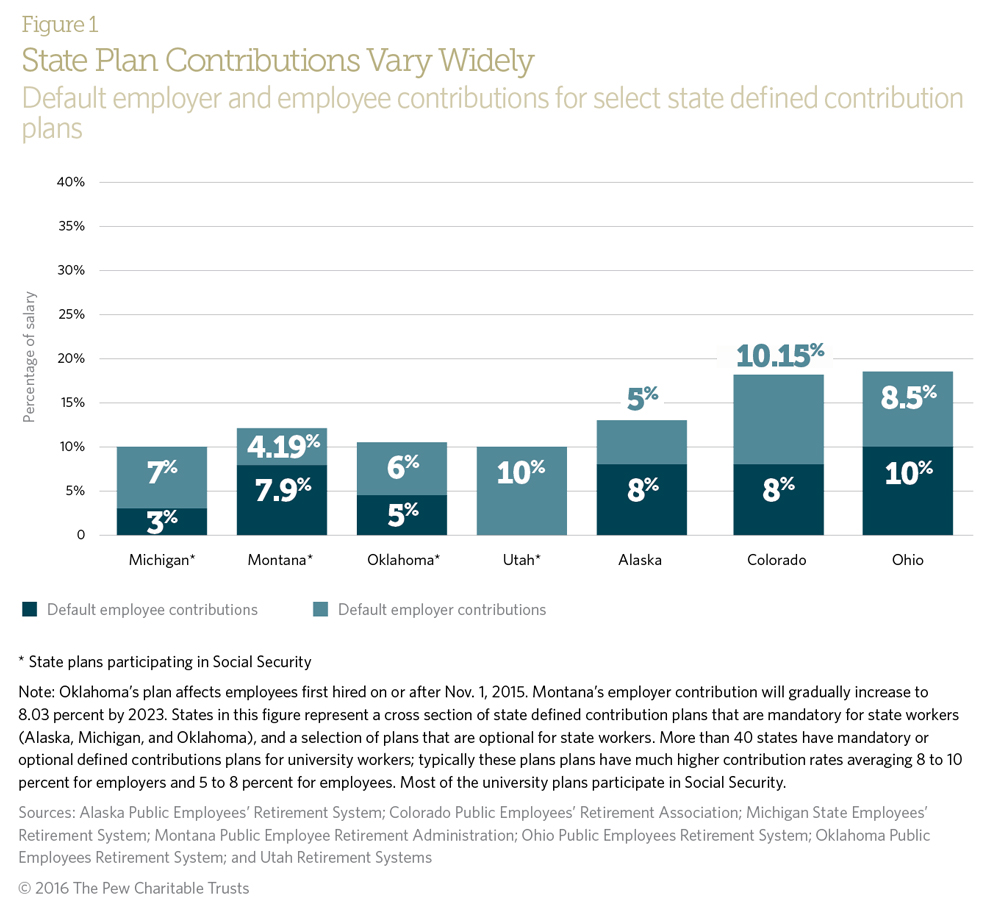

Several studies have found that most retirees need 70 to 80 percent of their final average salary in retirement from all sources of savings and benefits to maintain their pre-retirement standard of living.4 One analysis, based on achieving a replacement rate of about 80 percent of pre-retirement income, recommends a total annual savings rate of at least 12 percent of pay (18 percent for those not covered by Social Security).5 Figure 1 compares state contribution levels for a select sample of state defined contribution plans. Some states, like Michigan, have a mandatory defined contribution retirement plan, while others offer employees a choice between a defined contribution and a defined benefit plan.

State employees in Montana and Oklahoma receive smaller employer contributions than Michigan state workers, while Utah offers more generous state contributions.

Confidence in retirement security varies by age, income, and education

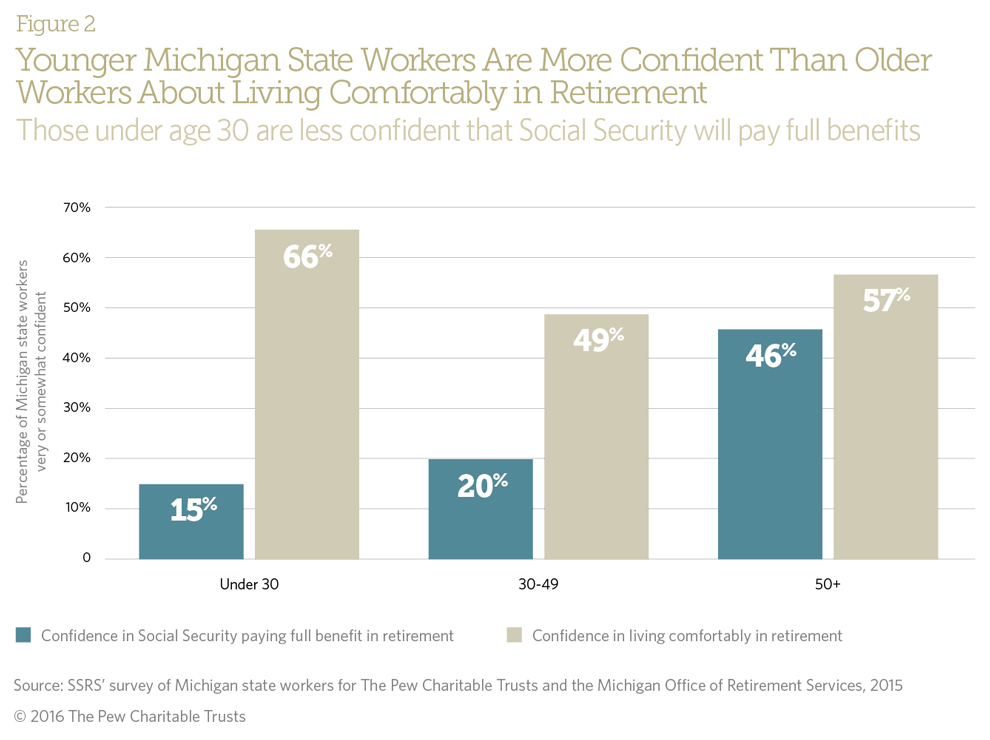

Michigan state workers expressed low levels of confidence when asked a range of retirement-related questions, most dramatically about whether the Social Security system would be able to fully pay their benefits in retirement. About a quarter (27 percent) said they were very or somewhat confident that Social Security would be able to provide them with their full benefits, while 71 percent said they were either not too or not at all confident in the program. Confidence in Social Security providing full benefits is lowest among younger workers, with only 15 percent of Michigan state workers under age 30 saying they were very or somewhat confident in the system, compared with 46 percent of those 50 and older.

Michigan state workers also voiced relatively low confidence about retirement security more generally and medical expenses. Just over half (54 percent) said they are very or somewhat confident that they will live comfortably in retirement, while 43 percent said they were very confident or somewhat confident in their ability to pay for medical expenses in retirement.

Retirement confidence among Michigan state workers follows a U-shaped pattern by age (see Figure 2), with confidence highest among younger and older workers and lowest for the middle-aged. About 66 percent of those under age 30 said they were somewhat or very confident, while 49 percent of 30- to 49-year-olds expressed confidence that they will have enough money to live comfortably in retirement. A greater number (57 percent) of those 50 and older said they feel confident about retirement, though that is still lower than for people in their 20s.

Confidence in the ability to pay for retirement also varies depending on income and education level, and is significantly lower for Michigan state workers with lower incomes and without a bachelor’s degree. About 46 percent of Michigan state workers earning less than $50,000 a year report being somewhat or very confident that they will have enough money in retirement, compared with 51 percent of those earning $50,000 to $99,999, and 71 percent of those making at least $100,000 a year. Meanwhile, about half (49 percent) of those with less than a college education are confident that they will live comfortably in retirement, compared with 57 percent of those with a college degree or more education.

Michigan state workers expect to retire earlier than workers nationwide, and almost all would like to receive some amount of their retirement benefit as guaranteed lifetime payments

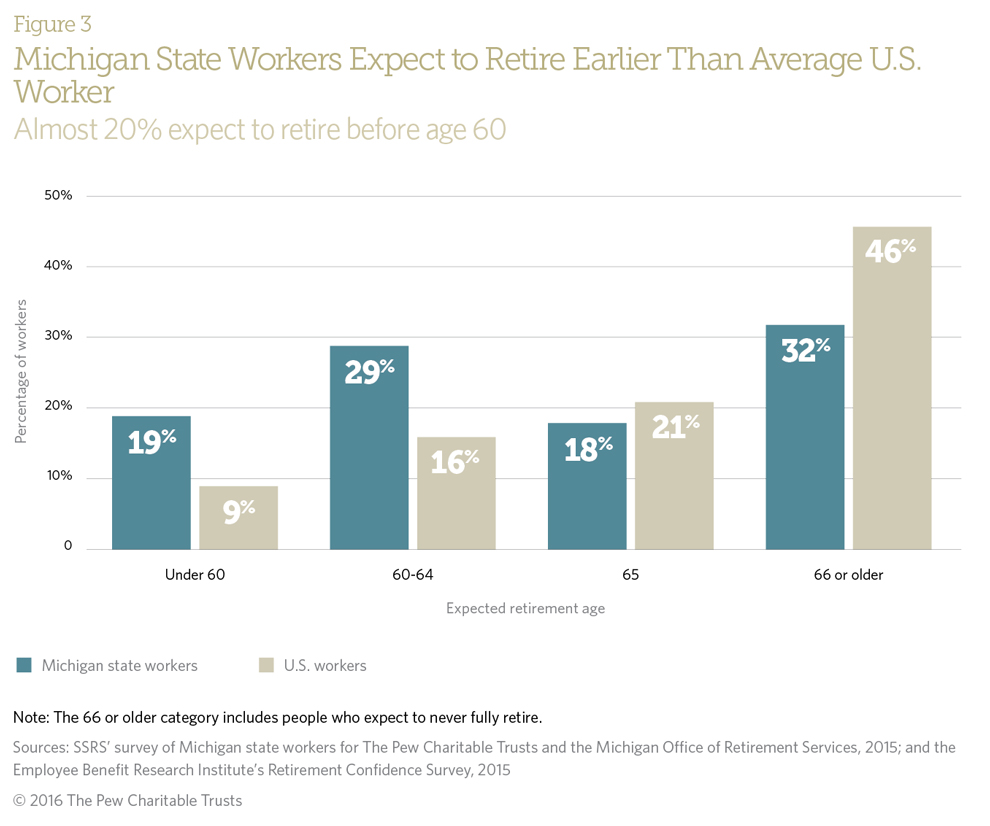

The expected age of retirement varies widely, but more Michigan state workers expect to be working after age 65 (32 percent) than retire before age 60 (19 percent). Nearly half expect to retire between ages 60 and 65, while 6 percent said they plan to never fully retire. In general, Michigan state workers plan to retire earlier than all workers nationwide. According to the Retirement Confidence Survey conducted in 2015, 9 percent of U.S. workers expect to retire before age 60, while 46 percent plan to retire after age 65.6 (See Figure 3.) Overall, 48 percent of Michigan state workers plan to retire before age 65, compared with 25 percent of all U.S. workers in the same survey.

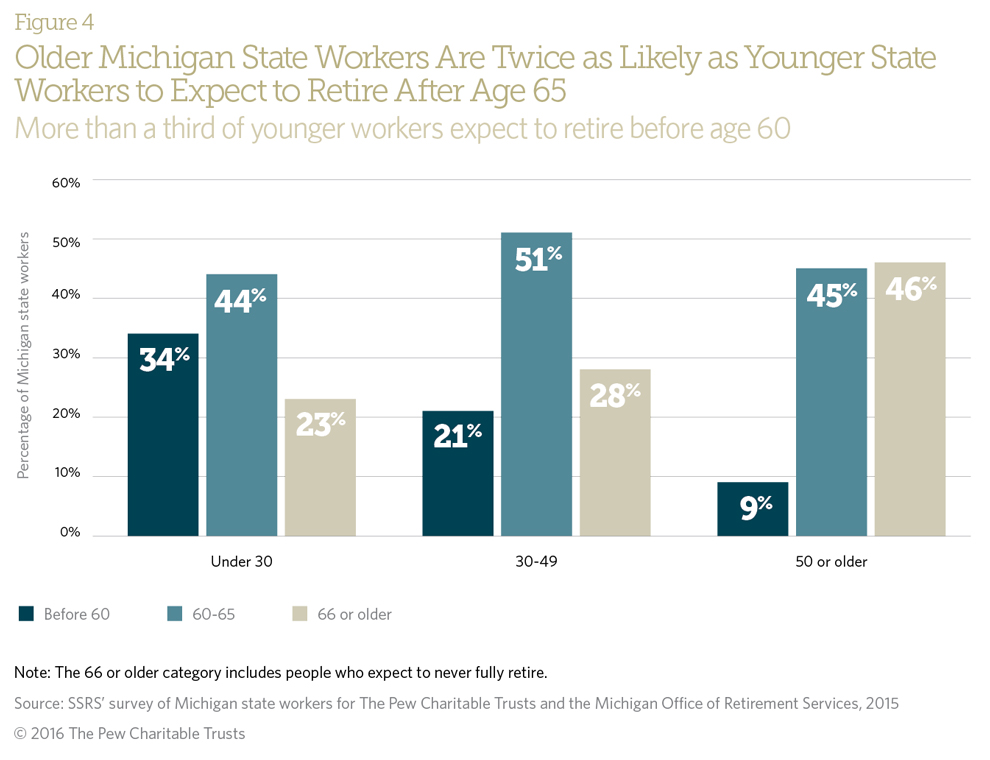

Michigan state workers are most likely to expect to retire between the traditional ages of 60 and 65, but the state survey suggests that younger workers are more likely to expect to retire earlier than older workers. Roughly 34 percent of those under age 30 expect to retire before age 60, while only 9 percent of those 50 or older plan to retire that early. (See Figure 4.) Michigan state workers 50 or older are twice as likely as workers under age 30 to expect to retire at age 66 or later (46 percent versus 23 percent).

Almost all Michigan state workers (92 percent) said they contribute to their retirement savings plan, and of those who do, 81 percent contribute enough—3 percent of pay—to get the maximum state match of 7 percent. Among those who contribute enough to receive the full match, about three-quarters said they contribute the most they can afford. This means most Michigan state workers are saving about 3 percent of their paychecks for retirement. Middle-aged workers, however, are most likely to say they are financially squeezed. Just 16 percent of those ages 40 to 49 said they can afford to contribute more, compared with 28 percent of workers under age 30 and 33 percent of those 65 and older.

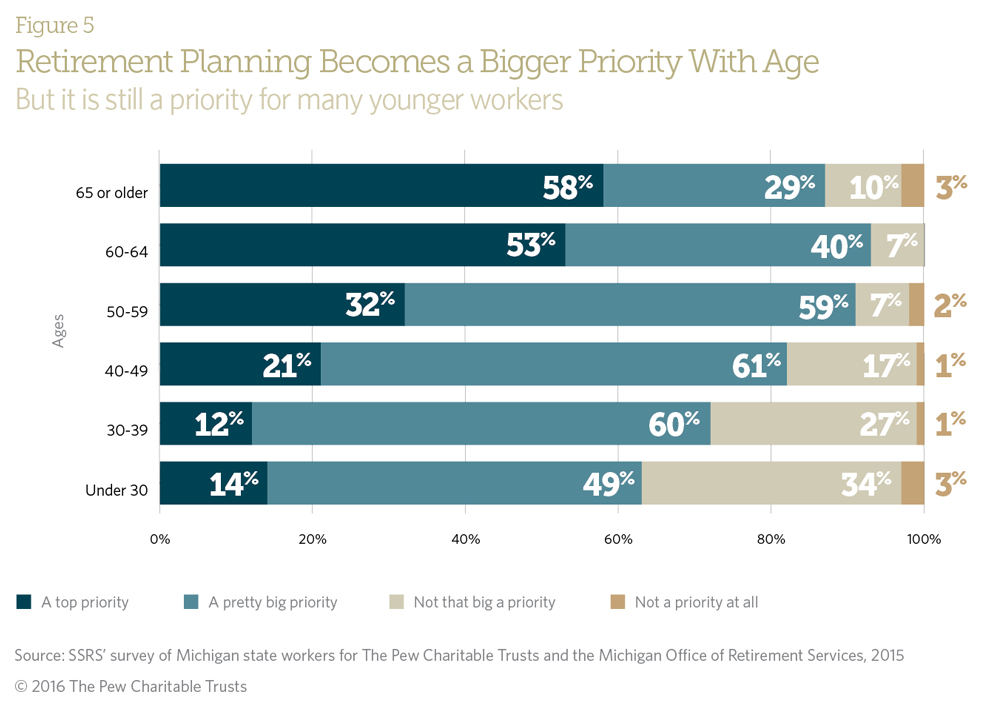

Only 22 percent of Michigan state workers listed retirement planning as a “top” priority, though a majority (57 percent) said it is a “pretty big” priority. Older state workers are more likely to use retirement planning services and to say that saving is a priority, though a majority of younger workers said it is a top or pretty big priority. Just 7 percent of 60- to 64-year-olds and 10 percent of workers 65 and older said that retirement planning was “not that big” a priority, compared with 27 percent of those ages 30 to 39 and 34 percent of those under age 30.

Despite the importance that Michigan state workers placed on retirement planning, many expressed uncertainty about how to best manage their retirement finances. They were more than two times as likely to say they prefer to manage their retirement investments themselves as have that done by their employer (67 percent to 31 percent). Still, only 5 percent said they were very confident in their own investing skills. Michigan state workers were more evenly divided when asked if they prefer that their retirement investments be managed by investment professionals (52 percent) or themselves (46 percent). Overall, the vast majority said they want to receive their retirement benefit either partially (42 percent) or entirely (47 percent) as a series of guaranteed lifetime payments. Only 11 percent answered that they want to receive their retirement benefit entirely as a lump sum.

Michigan state workers are generally satisfied with their compensation, and a majority would prefer more generous retirement benefits in exchange for lower salaries

Michigan state workers are generally satisfied with their salaries and benefits; 25 percent said they are very satisfied with their salary level, while more than half said they were somewhat satisfied (54 percent). About 17 percent said they are very satisfied with their retirement benefits, and 51 percent said they are somewhat satisfied. About 60 percent are very or somewhat satisfied with both salary and benefits.

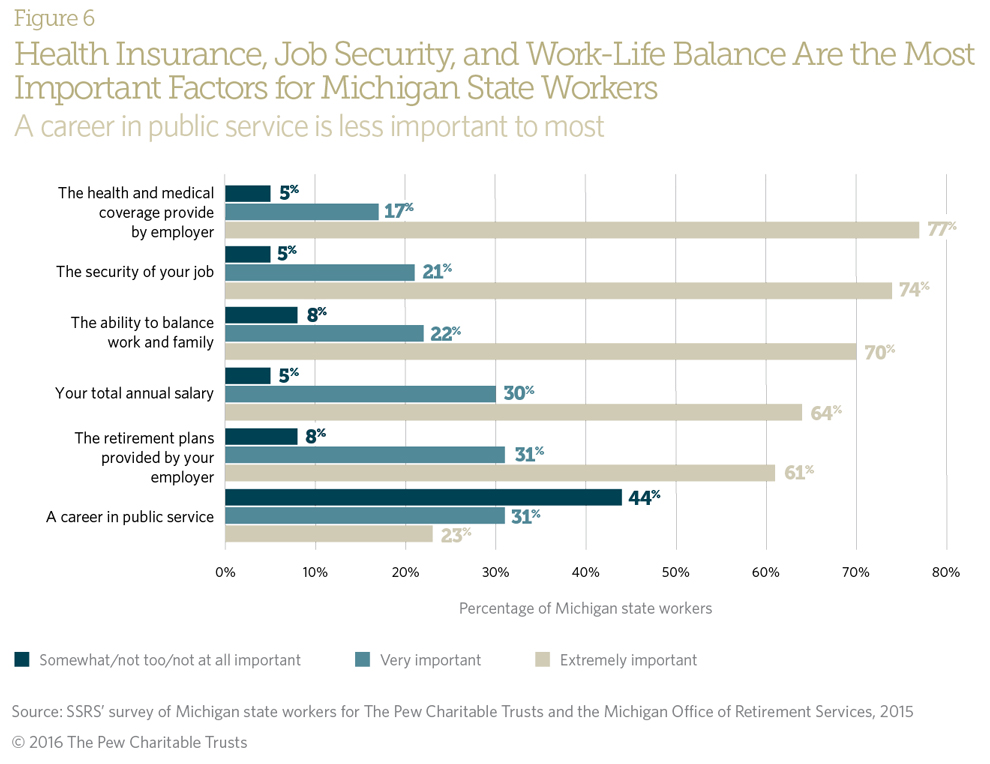

The survey asked respondents to rate the importance of various factors linked to work benefits and compensation. The state workers could rank each as extremely important, very important, somewhat important, not too important, or not at all important. Over 90 percent listed health coverage, salary, job security, retirement benefits, and work-life balance as either very or extremely important. (See Figure 6.) Most listed health coverage (77 percent), job security (74 percent), and work-family balance (70 percent) as extremely important factors. Salary and retirement plans were not far behind; 64 percent and 61 percent, respectively, listed these factors as extremely important.

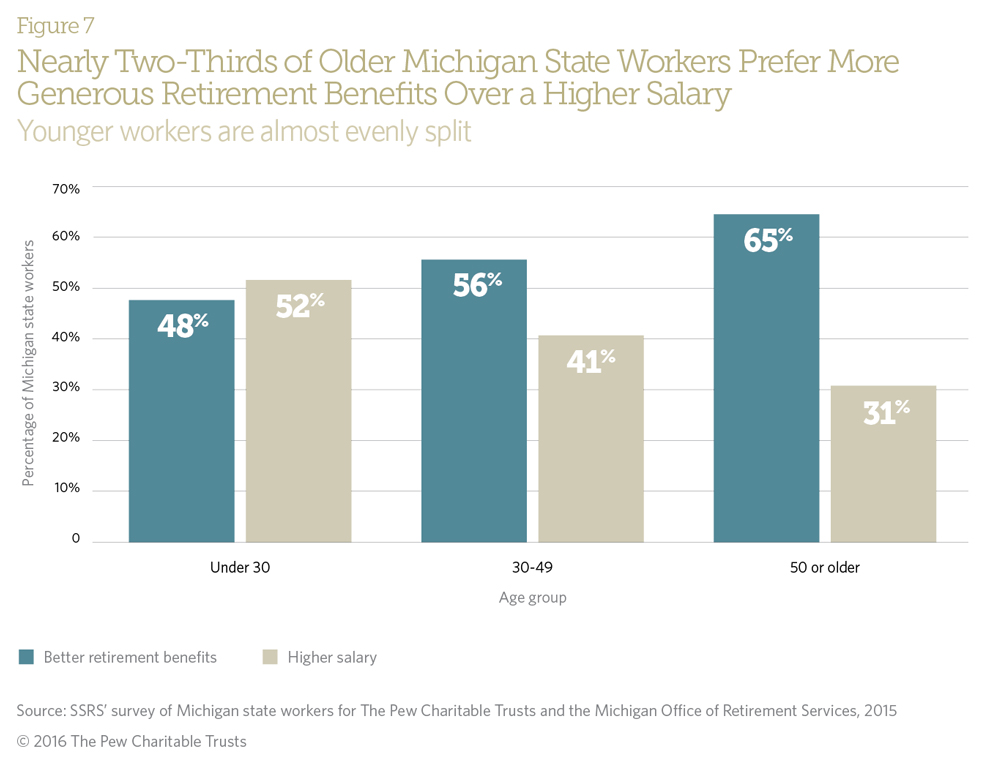

While younger Michigan state workers prefer higher salaries over generous retirement benefits, nearly half would rather have better benefits

Michigan state workers by a wide margin said that before working in the public sector, they expected the government to offer better retirement benefits than private employers (65 percent to 8 percent). A majority said they prefer more generous retirement benefits over higher salary. However, those with incomes under $50,000 are significantly more likely than those with incomes over $100,000 to say they prefer a job with a higher salary and fewer retirement benefits (46 percent compared with 33 percent) Furthermore, a slight majority of younger workers (52 percent) expressed a preference for higher salaries in exchange for less generous retirement benefits. (See Figure 7.) Michigan state workers who are at least age 50 are about two times more likely to say they would rather have more generous retirement benefits than higher salaries with less generous retirement benefits (65 percent versus 31 percent).

Most Michigan state workers said they do not expect to leave their jobs any time soon. About three-quarters (77 percent) expected to work for their current employer until retirement. Among workers under age 30, 53 percent expected to stay until retirement. Among the younger state workers anticipating a job change, about half expected to leave for the private sector.

There are some challenges to comparing Michigan state workers to national state and local workers across the U.S.

The Michigan survey was conducted as a follow-up to Pew’s 2013 national survey of state and local government workers. Several methodological considerations may limit comparisons between the surveys.

First, the Michigan survey was largely administered online, with a small percentage of respondents completing paper copies; the national survey, on the other hand, was conducted via telephone. Research has demonstrated that the survey mode can influence respondents’ answers, particularly on attitudinal questions for which respondents may feel pressure to answer in a more positive light in telephone interviews.7 This difference could have affected results. Second, Michigan state workers knew that their employer was a sponsor of the survey, which may have led them to answer certain questions more positively or negatively; neutral research organizations carried out the national survey.

In addition, all participants in the Michigan survey were state employees, but the national survey included teachers and local government workers. The surveys were conducted over a year apart, with the national survey fielding in the fall of 2013 and the Michigan survey in early 2015. Lastly, Michigan state workers are in a defined contribution retirement system, while most national state and local workers in the earlier survey were in defined benefit or pension plans.

Michigan state workers are similar in many ways to state and local workers nationwide, but they generally express lower retirement confidence and are less satisfied with their retirement benefits

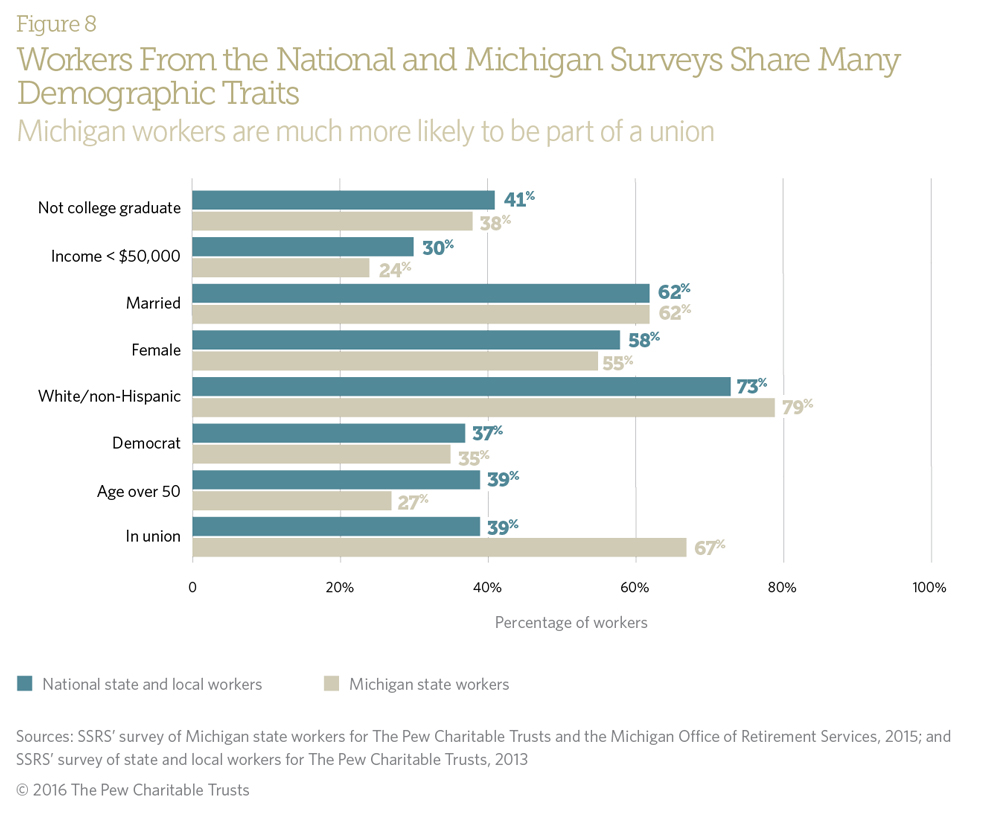

With those challenges in mind, a comparison of the Michigan and the national survey samples suggests that Michigan state workers and state and local workers across the country are similar in terms of such demographics as education, gender, marital status, race and/or ethnicity, and political affiliation. The national state and local worker sample is substantially older, however, and Michigan state workers are much more likely to be members of a union.

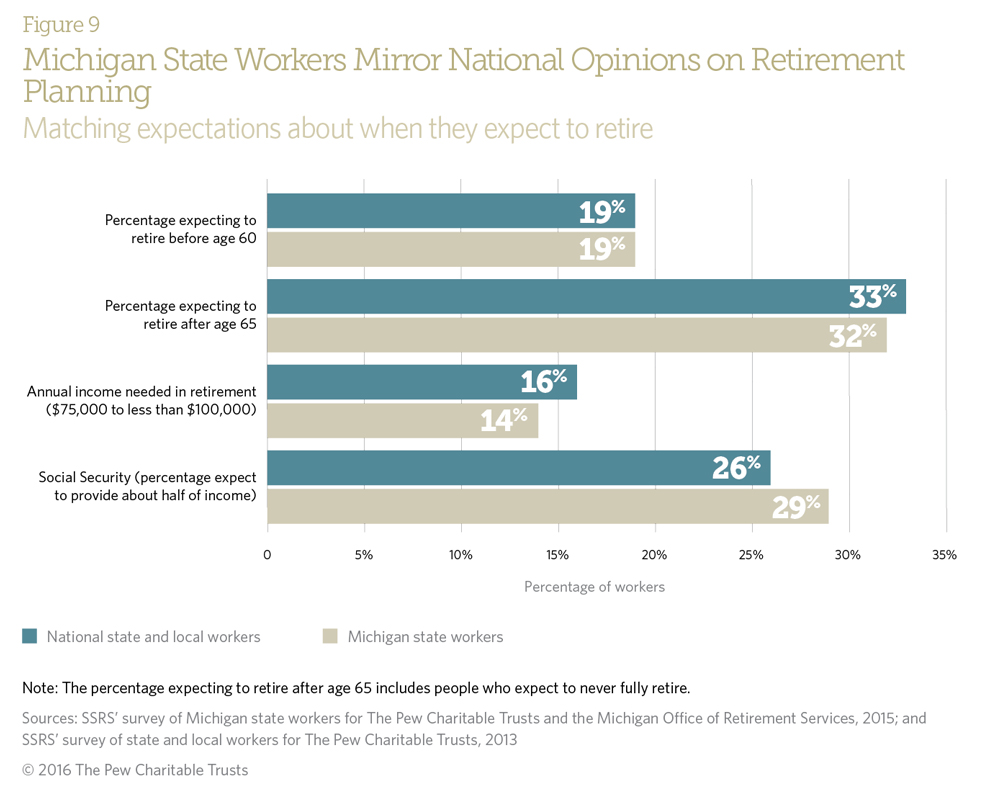

The two groups also report similar plans for retirement, including their expected retirement age, the income levels they think they will need in retirement, and how much they expect to rely on Social Security.

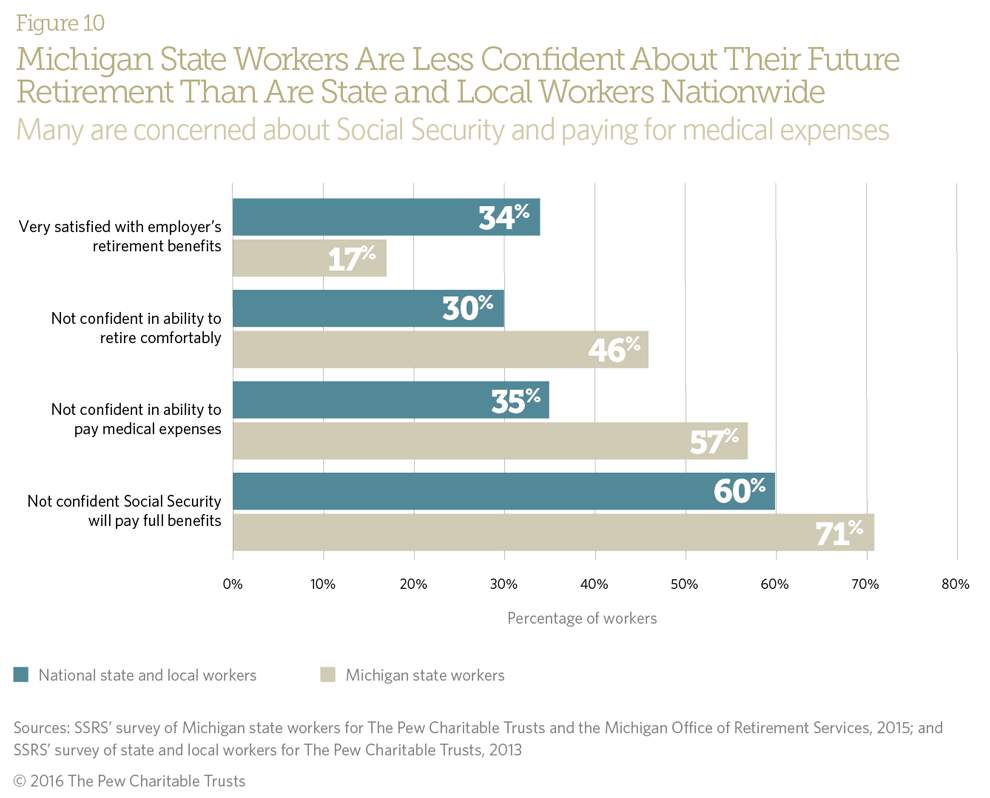

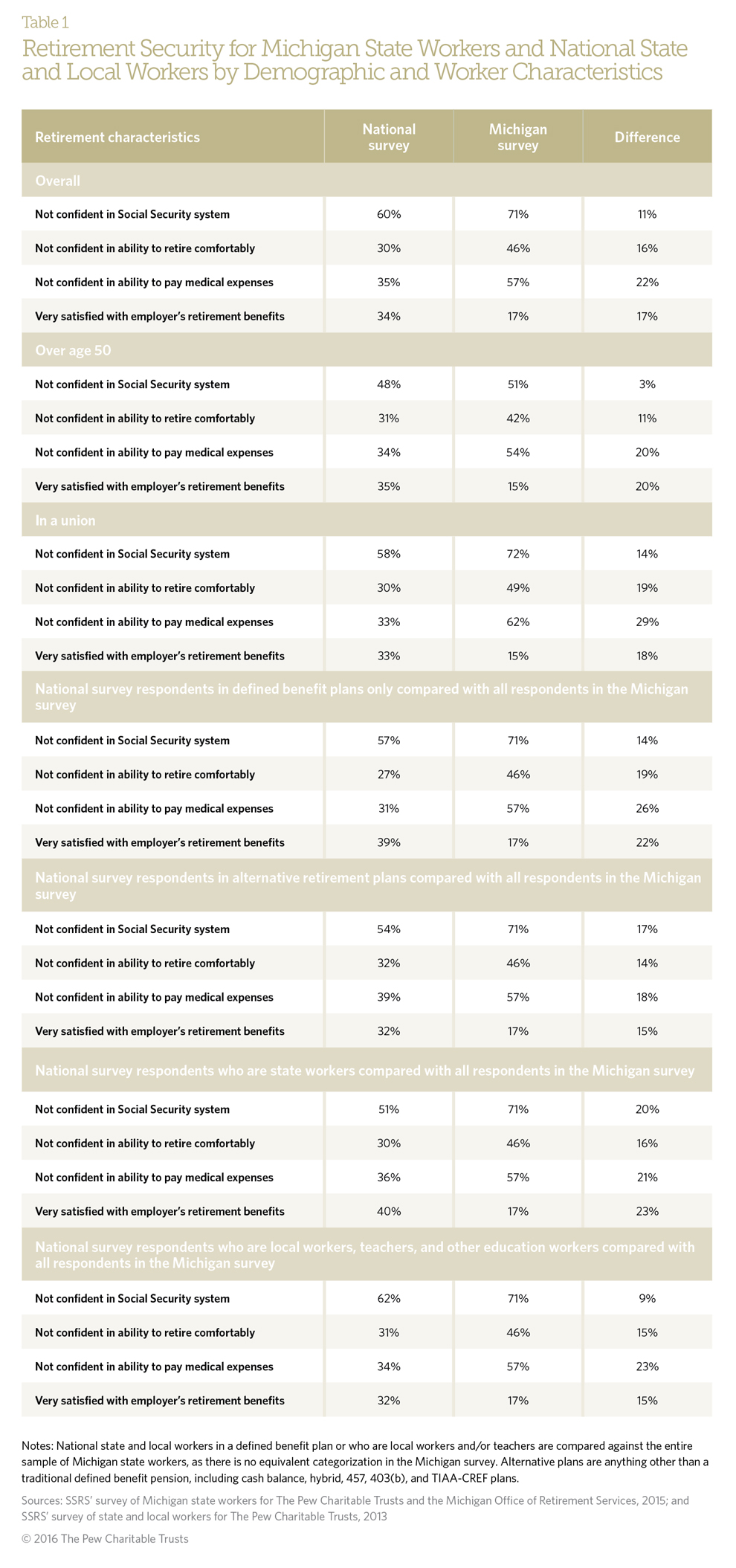

When compared with state and local workers across the nation, Michigan state workers report different views on their retirement security expectations. The Michigan cohort seems to have less confidence in retirement benefits in general, including in Social Security and their ability to pay for medical expenses. While 39 percent of workers in the national survey are very or somewhat confident that Social Security will pay full retirement benefits, only 27 percent of Michigan state workers expressed the same sentiment. Looked at another way, 60 percent of state and local workers nationally are not confident that Social Security will pay full retirement benefits. That rises to 71 percent of Michigan state workers. The Michigan workers also report less confidence that they will have enough money to retire comfortably, 54 percent compared with 69 percent in the national sample. They also said they feel less secure about their ability to pay medical bills, 42 percent compared with 65 percent of state and local workers nationwide.

Fewer Michigan state workers expressed high satisfaction with the retirement benefits provided by their employer than did those in the national survey (17 percent versus 34 percent very satisfied). The divide between the two groups is little changed when comparing the percentage of Michigan state workers who are either very or somewhat satisfied (68 percent) to state and local workers nationwide (85 percent). This gap appears to hold up

regardless of retirement plan and population characteristics. See Appendix B for more details.

Conclusion

Beginning in 1997, Michigan enrolled all new state workers in a defined contribution plan, which has become the primary retirement plan for state employees. The findings from our Michigan survey indicate that most employees participate and make sufficient contributions to receive the full employer match. However, Michigan state workers reported conflicting opinions about their future retirements. Most expect to retire at or before age 65, a lower age than U.S. workers in general, but they report less satisfaction with their retirement benefits and are less confident in Social Security or their ability to live comfortably after exiting the labor force than state and local workers nationwide.

Personal needs and preferences differ, however, and retirement confidence and job satisfaction often vary by workers’ demographic and economic situations. In particular, middle-aged state workers in Michigan appear to be less confident in their ability to retire comfortably. In addition, younger state workers are more likely to prefer higher salaries in exchange for less generous retirement benefits. Although the majority of Michigan state workers with defined contribution plans are generally satisfied with their retirement benefits, this survey highlights some challenges.

Appendix A: Methodology

The Michigan survey was conducted for The Pew Charitable Trusts and the Michigan Office of Retirement Services by SSRS, a national independent research company. A total of 6,000 state employees were invited to participate. The response rate was 41.5 percent, yielding a total sample of 2,471 employees enrolled in the defined contribution plan. Interviews took place between Jan. 5 and Feb. 23, 2015, with about 88 percent (n = 2,168) conducted online and 12 percent (n = 303) via mail. The margin of error was plus or minus 2.33 percentage points at the 95 percent confidence level.

Appendix B: Comparison of Michigan state workers and national state and local workers

Endnotes

- The expected retirement age of the average U.S. worker comes from the Retirement Confidence Survey and includes both public and private sector workers.

- There is also an additional contribution for employees who started on or after Jan. 1, 2012, and are not eligible to receive subsidized retiree health insurance. For these employees, employers contribute an additional 2 percent matching contribution that, along with the employee contribution, is apportioned to a personal health care fund to help pay for medical expenses in retirement.

- For more information on Michigan’s defined contribution plan for state workers see https://stateofmi.voya.com/einfo/pdfs/forms/michigan/640001/ MICH_PLAN_HIGHLIGHTS_GPS.pdf.

- John Karl Scholz and Ananth Seshadri, “What Replacement Rates Should Households Use?” working paper, University of Michigan Retirement Research Center (2009), http://www.mrrc.isr.umich.edu/publications/papers/pdf/wp214.pdf; and Aon Consulting, “Replacement Ratio Study: A Measurement Tool for Retirement Planning” (2008), http://www.aon.com/about-aon/intellectual-capital/attachments/human-capital-consulting/RRStudy070308.pdf.

- The study uses assumptions such as rate of return and annuitization rate that may be higher than current market levels. Roderick B. Crane, Michael Heller, and Paul J. Yakoboski, “Best Practice Benchmarks for Public Sector Core Defined Contribution Plans,” TIAA-CREF Institute (July 2008), https://www.tiaa-crefinstitute.org/public/pdf/institute/research/trends_issues/ pub_dc_plan_design_crane_heller_yako.pdf.

- Ruth Helman, Craig Copeland, and Jack VanDerhei, “The 2015 Retirement Confidence Survey: Having a Retirement Savings Plan a Key Factor in Americans’ Retirement Confidence,” EBRI Issue Brief, no. 413 (April 2015), https://www.ebri.org/pdf/briefspdf/EBRI_IB_413_Apr15_RCS-2015.pdf.

- Pew Research Center, “From Telephone to the Web: The Challenge of Mode of Interview Effects in Public Opinion Polls” (May 2015), http://www.pewresearch.org/2015/05/13/from-telephone-to-the-web-the-challenge-of-mode-of-interview-effects-in-public-opinion-polls/.