Aging Prison Populations Drive Up Costs

Older individuals have more chronic illnesses and other ailments that necessitate greater spending

This is the sixth analysis in a series examining how health care is funded and delivered in state-run prisons, as well as how care continuity is facilitated upon release.

Prison populations are shrinking, reflecting a decade-long movement by states to enact policies that reverse corrections growth, contain costs, and keep crime rates low. At the end of 2016, fewer people were held in state and federal prisons than in any year since 2004.

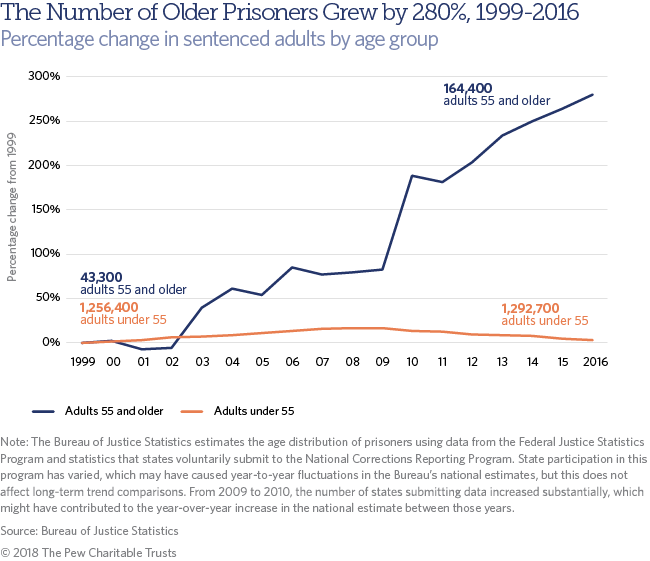

But despite this overall reduction, one group in prisons is surging: older individuals. From 1999 to 2016, the number of people 55 or older in state and federal prisons increased 280 percent. During the same period, the number of younger adults grew merely 3 percent. As a result, older inmates swelled from 3 percent of the total prison population to 11 percent.

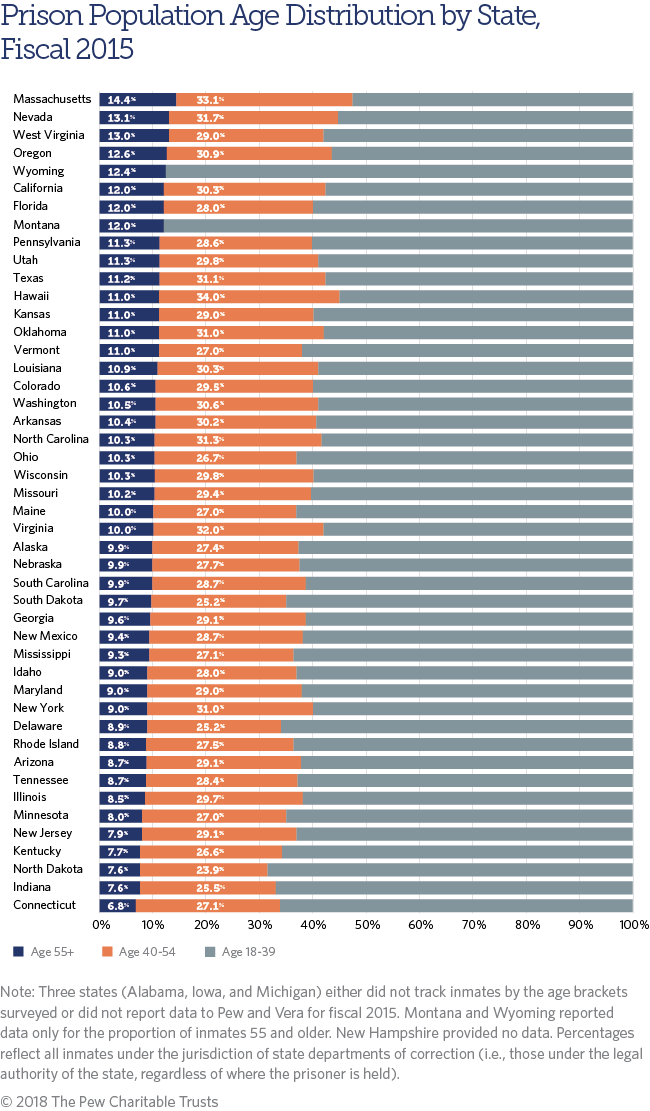

State prison populations account for the vast majority of these state and federal totals. A new report by The Pew Charitable Trusts finds that in 44 states that reported prison population data by age to researchers, the number of older individuals increased by a median of 41 percent from fiscal years 2010 to 2015, expanding from 7 percent of the total to 10 percent. Indeed, the share of older prisoners increased in every state that provided data, topping out in fiscal 2015 at a range of less than 8 percent in Connecticut, Indiana, Kentucky, New Jersey, and North Dakota to more than 12 percent in Massachusetts, Nevada, Oregon, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Greater need, greater expense

Like senior citizens outside prison walls, older individuals in prison are more likely to experience dementia, impaired mobility, and loss of hearing and vision. In prisons, these ailments present special challenges and can necessitate increased staffing levels and enhanced officer training to accommodate those who have difficulty complying with orders from correctional officers. They can also require structural accessibility adaptations, such as special housing and wheelchair ramps.

Additionally, as the Bureau of Justice Statistics found, older inmates are more susceptible to costly chronic medical conditions. They typically experience the effects of age sooner than people outside prison because of issues such as substance use disorder, inadequate preventive and primary care before incarceration, and stress linked to the isolation and sometimes violent environment of prison life.

For these reasons, older individuals have a deepening impact on prison budgets. Estimates of the increased cost vary. The National Institute of Corrections pegged the annual cost of incarcerating those 55 or older who have chronic and terminal illnesses at two to three times that for all others on average. More recently, other researchers have found that the cost differential may be wider.

At the federal level, an assessment by the Justice Department’s inspector general found that, within the Federal Bureau of Prisons, institutions with the highest percentages of aging individuals spent five times more per inmate on medical care—and 14 times more per inmate on medication—than those with the lowest percentages.

Why state prison populations are aging

The graying of state prisons stems from an increase in admissions of older people to prison and the use of longer sentences as a public safety strategy. From 2003 to 2013, admissions of those 55 or older increased by 82 percent—higher than the overall population growth for that age bracket—even as they declined for the younger group. A majority of these admissions were for new court commitments, which generally carry longer sentences than parole violations.

Across all ages and offense types, the average time expected to be served on a new court commitment rose from 29 months in 1993 to 39 months in 2013. Among those 55 or older in 2013, 40 percent had served 10 years or more, up from just 9 percent in 1993. As a result, individuals became more likely to grow old in prison. Six in 10 older inmates in 2013 had aged into that cohort, nearly double the share from 1993.

An additional explanation for the lengthy sentences is the nature of the crimes committed. Many of today’s older inmates were convicted of serious, violent felonies in their younger years. Between 1993 and 2013, two-thirds of people 55 or older in state prison were sentenced for a violent crime, such as assault, rape, or murder. This was the highest percentage among all age groups. Similarly, violent offenses were consistently the most common reason for new commitments among this group.

Matt McKillop is an officer and Alex Boucher is a senior associate with the states’ fiscal health project of The Pew Charitable Trusts.